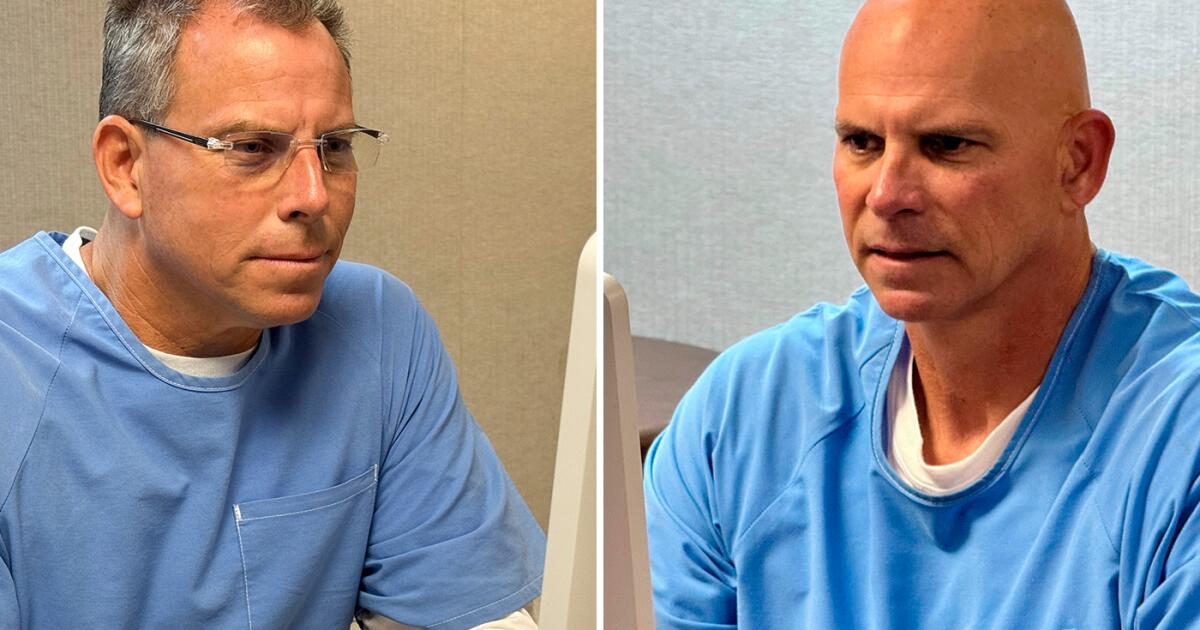

SACRAMENTO — A day after his younger brother was denied release, Lyle Menendez also saw California parole officials reject his bid for freedom, ruling he will remain behind bars for now for the 1989 shotgun murders of his parents.

The parole board grilled Menendez, 57, over his efforts to get witnesses to lie during his trials, the lavish shopping sprees he and his brother Erik, 54, took after their parents’ killings, and whether he felt relief after the murders.

“I felt this shameful period of those six months of having to lie to relatives who were grieving,” Menendez told the board. “I felt the need to suffer. That it was no relief.”

As the elder brother, Menendez said he at times felt like the protector of Erik, but that he soon realized the murders were not the right way out of sexual abuse they were allegedly suffering at the hands of their parents.

“I sort of started to feel like I had not rescued my brother,” he said. “I destroyed his life. I’d rescued nobody.”

The closely watched hearing for Lyle Menendez, one of the most well-known inmates currently in the state’s prison system, was thrown into disarray Friday afternoon after audio of his brother’s parole hearing on Thursday was publicly released.

The audio, published by ABC 7, sparked anger and frustration from the brothers’ relatives and their attorney, who accused the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation of leaking the audio and tainting Lyle’s hearing.

A CDCR spokesperson confirmed the audio was “erroneously” issued in response to a records request, but did not elaborate or immediately respond to additional questions from The Times.

“I have protected myself, I have stayed out of this, I have not had a relationship with two human beings because I was afraid, and I came here today and I came here yesterday and I trusted that this would only be released in a transcript,” said Tiffani Lucero-Pastor, a relative of the brothers. “You’ve misled the family.”

Heidi Rummel, Lyle Menendez’s parole attorney, also criticized CDCR, accusing the agency of turning the hearing into a “spectacle.”

“I don’t think you can possibly understand the emotion of what this family is experiencing,” she said. “They have spent so much time trying to protect their privacy and dignity.”

After the audio was published, Rummel said family members who planned to testify decided not to speak after all, and said she would be looking to seal the transcripts of Friday’s hearing.

Parole Commissioner Julie Garland said regulations allowed for audio to be released under the California Public Records Act. Transcripts of parole hearings typically become public within 30 days of a grant or denial, under state law.

During his first-ever appeal to the state parole board, Lyle Menendez was questioned over his credibility.

Garland referred to Menendez’s appeal to get witnesses to lie, plans to escape, and lies to relatives about the killings as a “sophistication of the web of lies and manipulation you demonstrated.”

Menendez said he had no plan at the time, there was just “a lot of flailing in what was happening.”

“Even though you fooled your entire family about you being a murderer, and you recruited all these people to help you … you don’t think that’s being a good liar?” Garland asked.

Menendez said the remorse he felt after the crimes perhaps helped create a “strong belief” he didn’t have anything to do with the killings.

Dmitry Gorin, a former Los Angeles County prosecutor, said the board’s decision denying parole was consistent with past decisions involving violent crimes.

“Although this is a high-profile case, the parole board rejecting the release demonstrates that it seeks to keep violent offenders locked up because they still pose a risk to society,” Gorin said. “Historically, the parole board does not release people convicted of murder, and this case is no different.

He called the decision a win for Los Angeles Dist. Atty. Nathan Hochman, who has opposed the brothers’ release.

The brothers were initially sentenced to life without the possibility of parole for the killings of their parents Jose and Kitty Menendez, but after qualifying for resentencing they gained a chance at freedom.

Many family members have supported their cause, but the gruesome crime and the brothers’ conduct behind bars led to pushback against their release.

The killings occurred after the brothers purchased shotguns in San Diego with a false identification and shot their parents in the family living room.

The bloody crime scene was compared by investigators to a gangland execution, where Jose Menendez was shot five times, including once in the back of the head. Evidence showed their mother had crawled, wounded, on the floor before the brothers reloaded and fired a final, fatal blast.

The brothers reported the killings to 911, according to court records. Soon afterward, prosecutors during the trial noted, the two siblings began to spend large sums of money, including buying a Porsche and a restaurant, which was purchased by Lyle. Erik bought a Jeep and hired a private tennis instructor.

Prosecutors argued it was access to their multimillion-dollar inheritance that prompted the killing after Jose Menendez shared that he planned to disinherit the brothers.

But during the trials, the Menendez brothers and relatives testified that the two siblings had undergone years of sexual and physical abuse at the hands of their father.

In contrast to their frenzy around their trial, Thursday and Friday’s parole hearings were quiet — yet occasionally contentious — affairs.

A Times journalist was the only member of the public allowed to view the hearing on a projector screen in a room inside the agency’s headquarters outside of Sacramento.

During the Friday hearing, the parole board quickly dived into the allegations that the brothers were sexually assaulted by their father, which Lyle Menendez said confused and “caused a lot of shame in me.”

“That pretty much characterized my relationship with my father,” he said, adding that the fear of being abused left him in a state of “hyper vigilance,” even after the abuse stopped and his father began to abuse Erik.

“It took me a while to realize that it stopped,” Menendez said. “I think I was still worried about it for a long time.”

Growing up, he said, taking care of his younger brother gave him purpose, and helped to protect him from “drowning in the spiral of my own life.”

Menendez alleged his mother also sexually abused him, but said he did not share it during his comprehensive risk assessment because he “didn’t see it as abuse really.”

“Today, I see it as sexual abuse,” he said. “When I was 13, I felt like I was consenting and my mother was dealing with a lot and I just felt like maybe it wasn’t.”

Board members also questioned Lyle Menendez on why he didn’t mention the possibility they were removed from their parents’ will in their submissions to the board, but Menendez contended their inheritance was not a motive in the killings.

Instead, he said, it became “a problem afterward” as they worried they would have no money after their parents’ deaths.

“I believe there was a will that disinherited us somewhere,” he said.

The result of Thursday’s hearing means Erik can’t seek parole again for three years, a decision that left some relatives and supporters of the younger brother stunned.

“How is my dad a threat to society,” Talia Menendez, his stepdaughter, wrote on Instagram shortly after the decision was made. “This has been torture to our family. How much longer???”

In a statement issued Thursday, relatives said they were disappointed by the decision and noted that going through Lyle’s hearing Friday would be “undoubtedly difficult,” although they remained “cautiously optimistic and hopeful.”

Friends, relatives and former cellmates have touted the brothers’ lives behind bars, pointing to programs they’ve spearheaded for inmates, including classes for anger management, meditation, and helping inmates in hospice care.

But members of the board questioned both siblings about their violation of rules, zeroing in at times about repeated use of contraband cellphones.

During the hearing Friday, Lyle said he sometimes used cellphones to keep in touch with family outside the prison. But Deputy Parole Commissioner Patrick Reardon questioned this explanation, and asked why Menendez needed a cellphone if he could make legitimate calls from a prison-issued tablet.

The rule violation, board members pointed out, had resulted in Menendez being barred from family visits for three years.

Reardon pointed out that Menendez pleaded guilty to two cellphone violations in November 2024 and in March 2025. Menendez was also linked to three other violations, although another cellmate of his took responsibility for those violations.

Menendez said the violations occurred when he lived in a dorm with five other inmates, and admitted the use of cellphones was a “gang-like activity.” The group, he said, probably went through at least five cellphones.

Heidi Rummel, Menendez’s parole attorney, argued in her closing that despite the cellphone issues, Menendez had no violent incidents on his prison record.

“This board is going to say you’re dangerous because you used your cellphones,” she said. “But there is zero evidence that he used it for criminality, that he used it for violence. He didn’t even lie about it.”

But members of the board repeatedly focused on what seemed to be issues of credibility. Reardon said at times it felt like Menendez was “two different incarcerated people.”

“You seem to be different things at different times,” Reardon said during the hearing. “I don’t think what I see is that you used a cellphone from time to time. There seems to be a mechanism in place that you always had a cellphone.”

Garland asked Menendez about whether he used his position on the Men’s Advisory Council — a group meant to be a liaison on issues between inmates and prison administrators — to manipulate others and gain unfair benefits.

Menendez said the position gave him access to wall phones, and used the position to help him barter or gain favors.

Garland also pointed to an assessment that found Menendez exhibited antisocial traits, entitlement, deception, manipulation and a resistance to accept consequences.

Menendez said he had discussed those issues, but that he didn’t agree he showed narcissistic traits.

“They’re not the type of people like me self-referring to mental health,” he said, adding that he felt his father displayed narcissistic tendencies and lack of self-reflection. “I just felt like that wasn’t me.”

Menendez pointed to his work to help inmates in prison who are bullied or mocked.

“I would never call myself a model incarcerated person,” he said. “I would say that I’m a good person, that I spent my time helping people. That I’m very open and accepting.”

The parole board applauded Menendez’s work and educational history while in prison, noting he was working on a master’s degree.

Despite the violations, Menendez argued he felt he had done good work in prison.

“My life has been defined by extreme violence,” he said, tears visible on his face. “I wanted to be defined by something else.”