Kennedy Center was always in the political spotlight but not like this

Last Tuesday, Philip Glass withdrew the delayed premiere in June of his latest symphony, No. 15. Originally meant to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in 2022, it is a portrait of Abraham Lincoln, but the composer decided the values of the current Kennedy Center were “in direct conflict to the message of the symphony,” which is inspired by Lincoln’s 1838 Lyceum Address.

In rebuke to Glass, Kennedy Center spokesperson Roma Daravi’s quick response was: “We have no place for politics in the arts.”

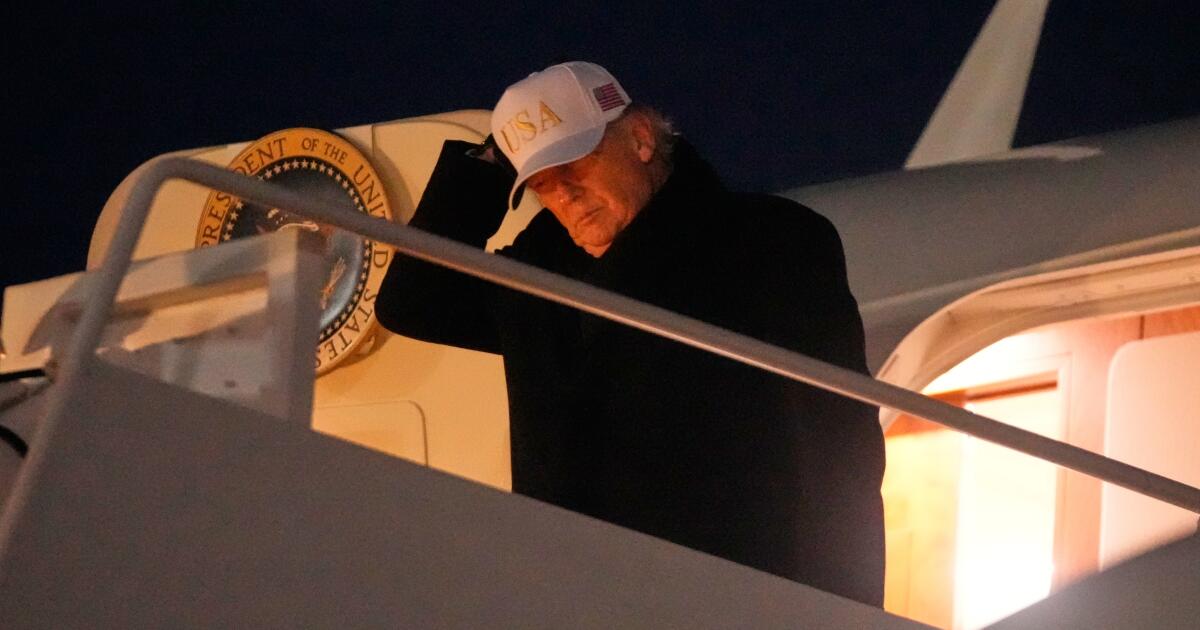

Two nights later, the chairman of the Kennedy Center board (who also happens to be president of the United States) hosted at the “no place for politics” center a bevy of Republican politicians and donors for the gala premiere of “Melania,” a documentary about and produced by his wife, the first lady.

Three days after that, the president, with no warning to Congress (which administers the Kennedy Center), center staff or the public, announced on his social media platform that he would close the facility July 4 for two years to undertake a major renovation. This may get the center off the hook for putting together a new season, what with all its departures (voluntary and not) of competent artistic directors, but it also means the center’s one remaining major institution, and its crown jewel, the National Symphony, is suddenly homeless.

The fact is, the Kennedy Center has always been political. The same goes for orchestras. And Lincoln’s seeming role as a symphonic football is nothing new, either.

But political doesn’t — or, at least, once didn’t — necessarily imply partisan. In March 1981, two months into his presidency, Ronald Reagan turned up at the Kennedy Center for the premiere of a new production of Lillian Hellman‘s “The Little Foxes,” and was photographed happily congratulating a smiling Elizabeth Taylor backstage. Also present was the gruff playwright.

Hellman, who had been a member of the Communist Party and was called up in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1952, and Reagan, an avid anti-Communist, couldn’t have had much use for each other politically. But there they were, soaking up art and glamour (if maybe not in that order) together. It was also in 1952 and thanks to Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s Communist witch hunts that the first inklings of a national performing arts center in Washington, D.C. developed.

Aaron Copland’s “Lincoln Portrait,” for speaker and orchestra, written in 1942 in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attack, had been slated for a performance at Dwight D. Eisenhower’s inauguration in 1952. Complaints about Copland’s leftist leanings pressured Eisenhower to cancel the performance, but left inklings in Ike’s mind that the nation needed a performing arts center in Washington, D.C. In 1955, he instituted a District of Columbia Auditorium Commission and that led to the National Cultural Center Act of 1958.

Bipartisan support became a no-brainer. Kennedy was an enthusiast and, in his presidency, both First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy and former First Lady Mamie Eisenhower worked together to support the cultural center. In 1963, just days before his assassination, JFK hosted a White House fundraiser for the center. A year later, President Lyndon B. Johnson broke ground for what was to become “a living memorial to John F. Kennedy” with the gold-plated spade that President Taft had used for the Lincoln Memorial.

President Lyndon B. Johnson lifts a shovel full of dirt during ground-breaking ceremonies for the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in 1964 while members of the Kennedy family look on.

(Bettmann Archive / Getty Images)

The Kennedy Center proved political from Day 1. Leonard Bernstein was commissioned to write a theatrical piece for the center’s opening in 1971, which turned out to be an irreverent “Mass” — musically, liturgically, culturally and, most assuredly, politically. Most of all it was an unmistakably protest against the Vietnam War. In his own protest, President Nixon stayed home.

“Mass” was ridiculed by critics and sophisticates. And so was the Kennedy Center in its monstrosity. But the composition ultimately came to be seen as a precursor of musical Postmodernism and possibly Bernstein’s greatest work, a monument in its own right. The Brutalist monumentalism of the Kennedy Center also grew over time to be loved, increasingly bringing cachet to a diverse nation’s artistic needs.

All of that has, however, been called into question by a new administration noisily remaking the center as partisan and politicizing even renovation and Lincoln.

You don’t take on renovation of a single concert hall overnight, let alone an entire performance center with several theaters, including a major concert hall and opera house. This requires architects and acousticians deeply schooled in theaters, and each has its own acoustical needs. You touch anything, and it will affect the sound. Both the opera house and concert hall could use acoustical work, but that is a very big deal. If this sudden renovation comes as a surprise to staff, that means there have been no consultations, no proposals, no models, no feedback. Best to add to the budget some hundreds of millions of dollars to fix mistakes.

Before even considering anything else, a space has to be found for the National Symphony. It is possible to create temporary structures or renovate existing buildings into acoustical wonders, as architect Frank Gehry and acoustician Yasuhisa Toyota have proved. In Munich, the temporary Isarphilharmonie, which has Toyota acoustics, is so successful that some are saying the city doesn’t need a new concert hall after all.

So, given the timing of this precipitous announcement, it is hard to believe that something isn’t also going on with attitudes toward Lincoln and Glass’ displeasure with the Kennedy Center administration. For what it’s worth, Presidents Ford, Carter, George H.W. Bush, Clinton and Obama have all narrated Copland’s “Lincoln Portrait.”

Lincoln has been central to Glass’ work for more than four decades. The composer first used Lincoln in Act V (known as “The Rome Section”) of Robert Wilson’s 12-hour opera, “the CIVIL warS: a tree is best measured when it is down” (a prescient title for current Kennedy Center thinking), which had been intended for the 1984 Olympic Arts Festival in L.A. but was never produced here for lack of funds.

Lincoln shows up in Glass’ 2007 opera, “Appomattox,” commissioned by San Francisco Opera and later revised and expanded for Washington National Opera in 2015. The opera offers a look at how the Civil War ended with high-minded statesmanship. The first act of Glass’ 2013 opera, “The Perfect American,” about the last days of Walt Disney, ends with a flashback of Walt, who idolized Lincoln, visiting Disneyland and getting into an argument about slavery with the animatronic Lincoln, which gets so worked up it attacks Walt.

Politics are rarely far away from orchestral or operatic life. At a recent appearance of the Chicago Symphony at the Soraya, Italian conductor Riccardo Muti followed an impressively grand performance of Brahms’ Fourth Symphony by telling the audience how the arts keep us honest and played as an encore the overture to Verdi’s “Nabucco,” as an example of how an opera could motivate public support for Garibaldi’s nationalist movement. Garibaldi also makes an appearance with Lincoln in the Glass/Wilson “Rome Section.”

A few days later at the Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall, the thrilling Orquesta Sinfónica de Minería from Mexico City revealed an inspiring model of Latin American cooperation. On the program was Cuban composer Paquito D’Rivera’s “Concerto Venezolano,” featuring the fearless improvising Venezuelan trumpet soloist Pacho Flores. The concerto also featured solos on the Venezuelan cuatro by Héctor Molina, but his name was only announced last minute, due to current travel uncertainty.

One of the greatest recordings of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, his grab-you-by-the-gut answer to Stalin and celebration of Russia, is by the National Symphony under Mstislav Rostropovich, recorded in 1994 at the Kennedy Center. Stalin saw the symphony as his deification. Rostropovich exuded, in the Kennedy Center aura, the expression of an overwhelmingly triumphant celebration of the end of the Soviet repression. You can take the symphony and the opera out of the Kennedy Center, but you can’t take the essence of the Kennedy Center, the living memorial to the ideal of something larger than political ego, out of the symphony and opera.