Highlights from our Feb. 26 issue

We made it! After this weekend, when the Producers Guild of America and Screen Actors Guild hand out their highly predictive precursors, the final shape of the Oscar race should be (reasonably) clear — and nominees worn out by months of campaigning will be breathing a sigh of relief.

Before I share highlights from this week’s issue, one programming note: This will be my last letter from the editor until our inaugural Cannes issue drops in May. (Don’t worry, I will be plenty busy in the interim catching up on this year’s top Emmy contenders.)

Thanks as always for following along, and may you triumph in your Oscar pool!

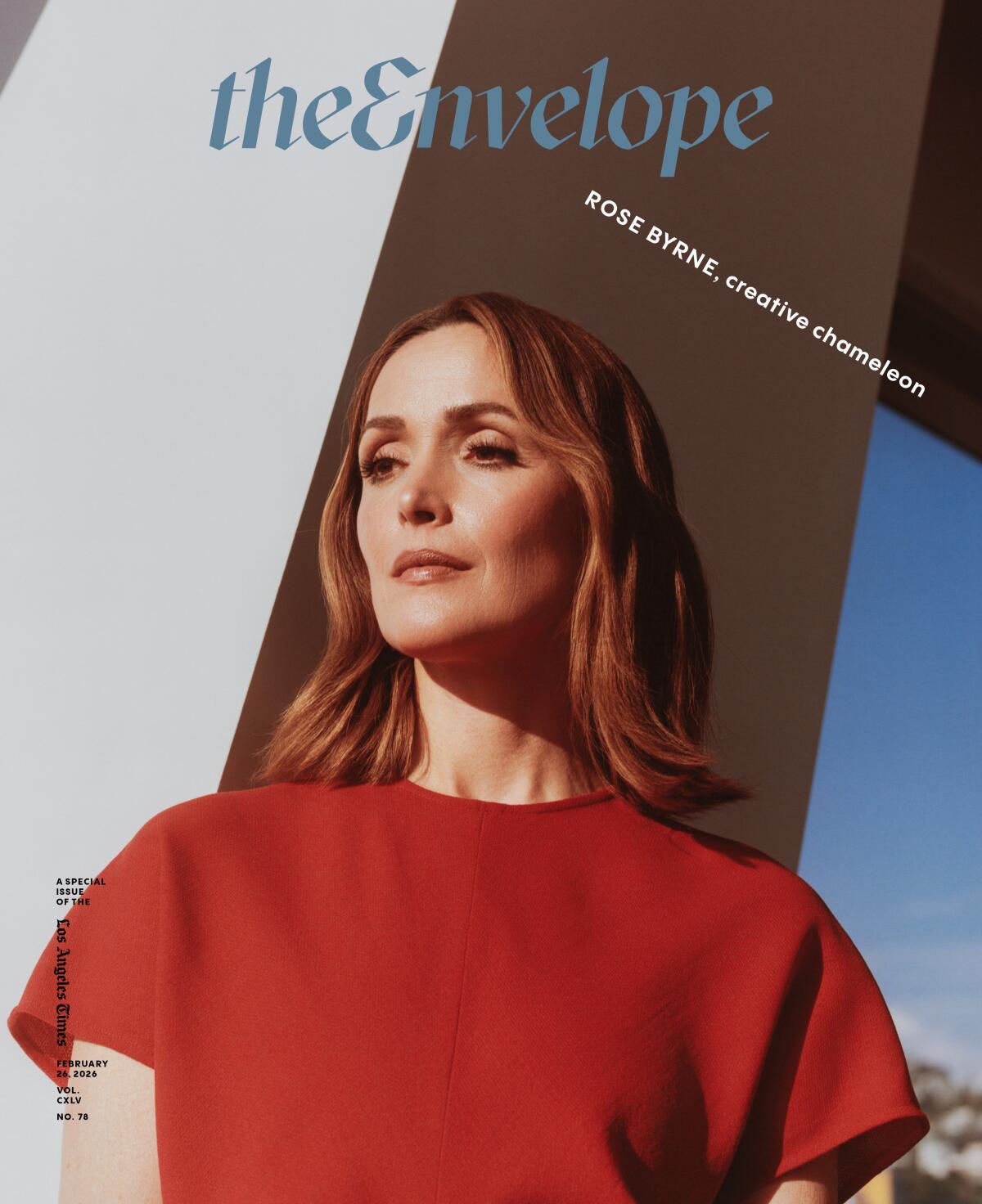

Cover story: Rose Byrne

(Ryan Pfluger / For The Times)

Times columnist Mary McNamara and I don’t agree on everything, but we do agree on this: “Damages” deserves to be ranked alongside “Mad Men” and “Breaking Bad” in any discussion of the Golden Age of TV.

That’s thanks in one part to a gripping flash-forward narrative structure now so common it could be considered a cliché, and in another to Glenn Close’s indelible performance as ruthless litigator Patty Hewes. But it’s also a testament to the multifaceted talents of Rose Byrne, who went “toe-to-toe” with Close in what would become her breakthrough role — and then confidently pivoted to projects like “Insidious,” “Bridesmaids” and “Spy.”

“Byrne is something of a creative chameleon, moving easily from drama to comedy to horror, film to television to stage and back again,” McNamara writes in this week’s cover story. “In many ways, her gut-wrenching, darkly funny performance as a woman pushed beyond all endurance in “If I Had Legs I’d Kick You” is a culmination of all the characters she brought to life before it.”

Inside Warner Bros.’ dominant Oscar haul

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

Whether you come down on the side of “Sinners” or “One Battle After Another” in the best picture race may be perfect fodder for debate with friends over a few small beers, but for Warner Bros. executives Mike De Luca and Pam Abdy it would be akin to choosing a favorite child. After all, both projects emerged from the pair’s desire, as contributor Gregory Ellwood writes, to make WB “a destination where filmmakers of all varieties, including auteurs, bring their projects for ‘white glove’ treatment.”

As De Luca explains, “Everything was original once… If you don’t refresh the coffers with new IP to create new franchises, at some point you get to Chapter 10 or 11 and people start to move on.”

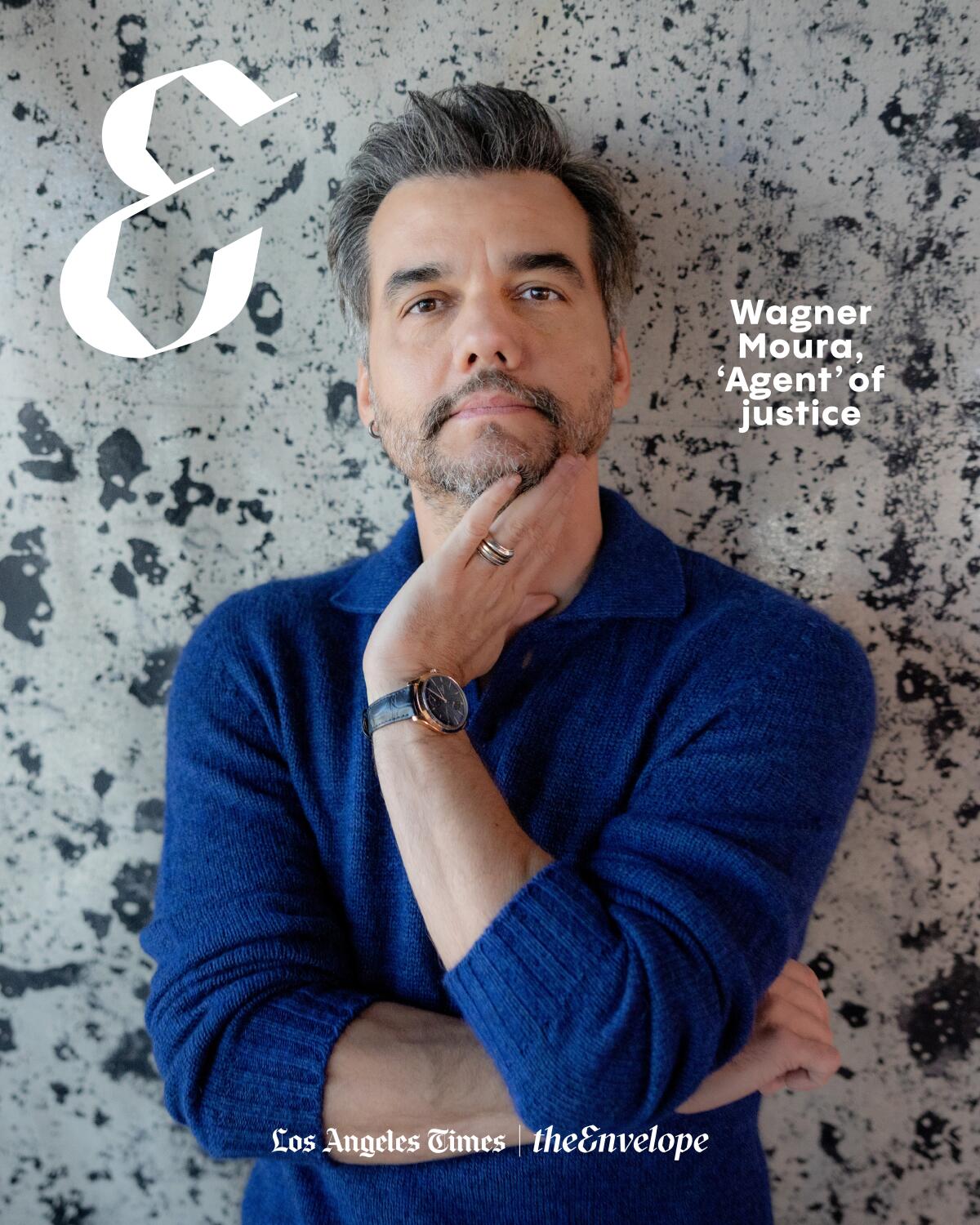

The many faces of ‘The Secret Agent’

(Ryan Pfluger/For The Times)

The moment Tânia Maria arrives onscreen as Dona Sebastiana in “The Secret Agent,” you can’t help but ask yourself, “Who is that?!” (Star Wagner Moura had the same reaction.) But the real feat casting director Gabriel Domingues pulls off in the Oscar-nominated Brazilian thriller is to make you ask yourself the same question, over and over, every time a new character appears.

How did Domingues find a range of actors to represent the country’s endless diversity? It’s part of his process, writes contributor Carlos Aguilar: “He prides himself on doing the shoe-leather work of looking for fresh, compelling faces in cities where others might not think to look — those without a prominent arts scene, for instance.”