Prep talk: Hunter Greene continues to inspire, encourage next generation

Ever since Hunter Greene stepped foot on campus at Sherman Oaks Notre Dame High as a 14-year-old freshman, everyone has predicted stardom in baseball. But one day, it will be remembered how much he has done to help inspire and encourage the next generation of students to follow their dreams.

Greene, the No. 2 draft pick of the Cincinnati Reds in 2017, has become a member of the team’s starting rotation while continuing to serve as a role model for others.

On Saturday, he returned to Notre Dame to present two scholarship awards from his foundation given annually to a boy and girl who demonstrates character and commitment to their community. It’s the seventh and eighth scholarships since he began the annual presentation four years ago.

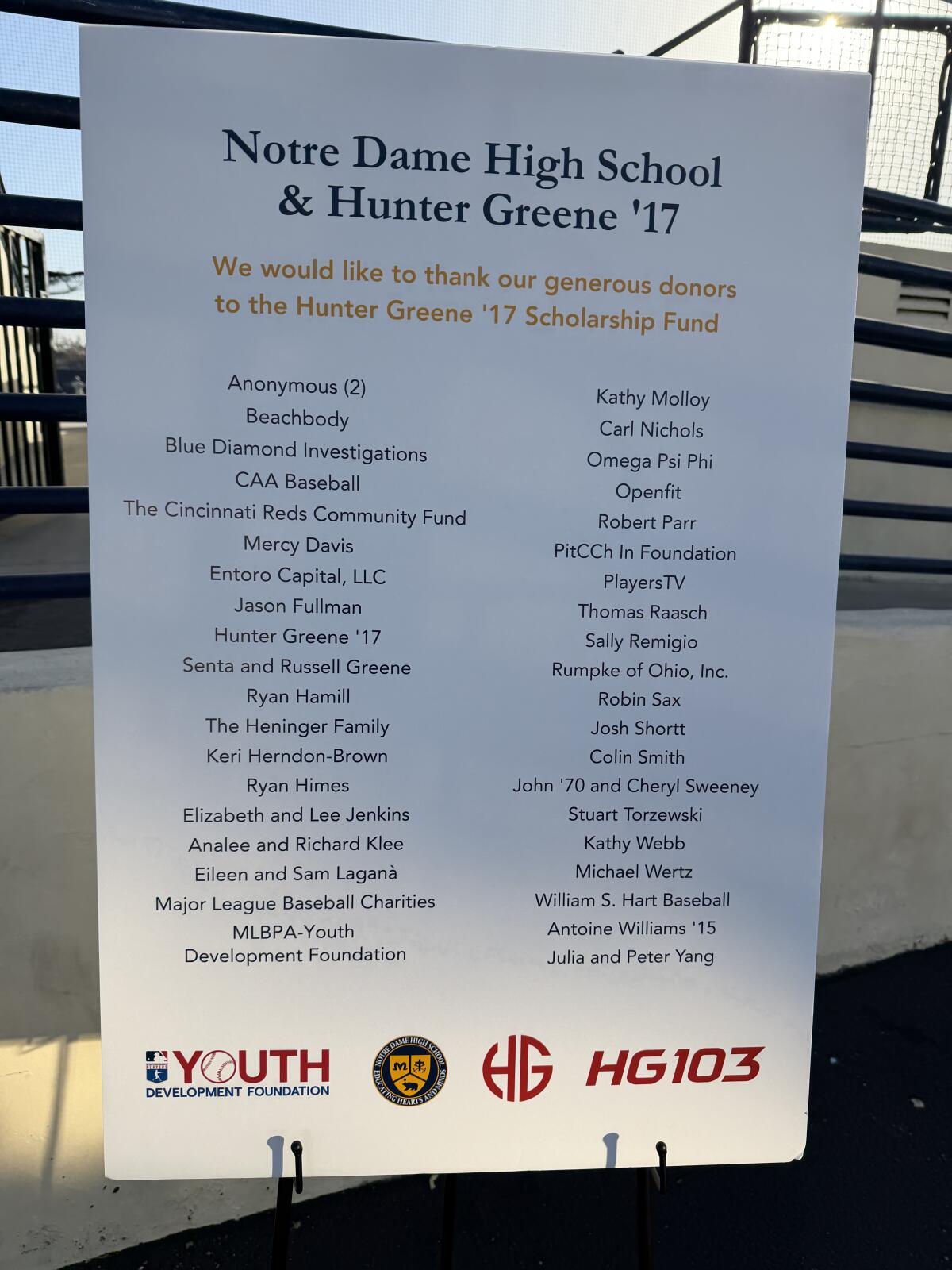

Donors list for the Hunter Greene Scholarship Fund at Sherman Oaks Notre Dame.

(Eric Sondheimer / Los Angeles Times)

Even in high school, Greene was seen as someone who could be a leader in helping others. He embraced that role and has continued as a professional baseball player, whether it’s at his former school or helping youth around the country.

Notre Dame held an alumni baseball game, where former major leaguers Brendan Ryan and Brett Hayes were among the participants.

Greene did not play, but what he continues to do off the field is admired and much appreciated.

This is a daily look at the positive happenings in high school sports. To submit any news, please email eric.sondheimer@latimes.com.