Five films that capture the Latino immigrant journey

The ongoing ICE sweeps taking place across Los Angeles and the country have underscored the many challenges faced by immigrant communities. For decades, migrants across Latin America have traversed rugged terrain and seas in search of a better life in the United States, often risking their lives in the process. Various films have captured the complexities of the Latino immigrant experience. Here are five of them.

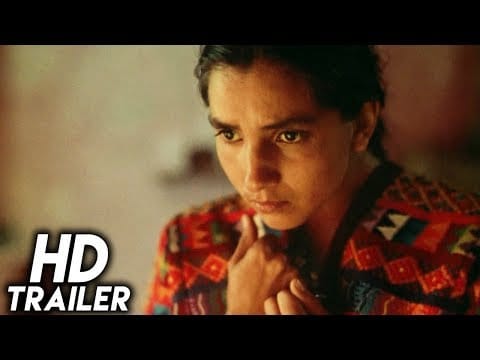

“El Norte” (1983) directed by Gregory Nava

Siblings Rosa and Enrique Xuncax (played by Zaide Silvia Gutiérrez and David Villalpando, respectively) decide to flee to the U.S. after their family is killed in the Guatemalan Civil War, a government-issued massacre that decimated the country’s Maya population. After a dangerous trek through Mexico, Rosa and Enrique find themselves in Los Angeles, the land of hopes and dreams — or so they think. The 1983 narrative is the first independent film to be nominated for an Academy Award for original screenplay; it was later added to the National Film Registry in 1995.

Decades later, “El Norte” still feels prescient.

“[Everything] that the film is about is once again here with us,” Nava told The Times in January. “All of the issues that you see in the film haven’t gone away. The story of Rosa and Enrique is still the story of all these refugees that are still coming here, seeking a better life in the United States.”

“Under the Same Moon” (2007) directed by Patricia Riggen

Separated by borders, 9-year-old Carlitos (Adrián Alonso) yearns to reunite with his mother, Rosario (Kate del Castillo), who left him behind in Mexico with his ailing grandmother. After his grandmother passes, Carlitos unexpectedly flees alone to find his mother in Los Angeles, encountering harrowing scenarios as he pieces together details of her exact location. Directed by Patricia Riggen as her first full-length feature, it made its debut at Sundance Film Festival in 2007, where it received a standing ovation.

“All these people risked their lives crossing the border, leaving everything behind, for love,” says Riggen. “For love of their families who they’re going to go reach, for love of their families who they leave behind and send money to. But it always has to do with love and family.”

“Una Noche” (2012) directed by Lucy Mulloy

There is no other option but the sea for the three Cuban youths in “Una Noche” who attempt to flee their impoverished island on a raft after one of them, Raúl, is falsely accused of assaulting a tourist. Lila follows her twin brother Elio, who is best friends with Raúl, but all is tested in the 90 miles it takes to get to Miami. The 2012 drama-thriller premiered in the U.S. at the Tribeca Film Festival, where it won three top awards; its real-life actors Anailín de la Rúa de la Torre (Lila) and Javier Nuñez Florián (Elio) disappeared during the screening while in a stopover in Miami, later indicating that they were defecting.

By this time, it was not uncommon to hear of Cuban actors and sports stars defecting to the U.S.

“[Anailín and Javier] are quite whimsical and I can see how they’d decide to do something like this,” said director Lucy Mulloy when the news broke in 2012. “But this is also an important life decision, and no one in Cuba takes it lightly.”

“I’m No Longer Here” (2019) directed by Fernando Frías de la Parra

Ulises (Juan Daniel García Treviño) shines as the leader of Los Terkos, a Cholombiano subculture group in Monterrey known for their eclectic fashion and affinity for dancing and listening to slowed down cumbias. But after a misunderstanding makes him and his family the target of gang violence, he flees to New York City, where he must learn to navigate the unknown world as an individual at its fringes. The 2019 film swept Mexico’s Ariel awards upon its release and was shortlisted in the international feature film category to represent Mexico at the 93rd Academy Awards.

The contemporary film provided a nuanced perspective on the topic of migration that did not always hinge on violence.

“The idea was to have a film that is more open and has more air so that you can, as an audience, maybe see that yes, violence is part of that environment,” said director Fernando Frías de la Parra to The Times in 2021. “But so is joy and growth and other things.”

“I Carry You With Me” (2020) directed by Heidi Ewing

Iván’s (Armando Espitia) life appears at a standstill — he’s a busboy with aspirations of becoming a chef, and a single dad to his 5-year-old son who lives with his estranged ex. But his monotonous life changes when he meets Gerardo (Christian Vázquez) at a gay bar, which shifts his journey into a blooming love story that traverses borders and decades. The story is inspired by the real-life love story of New York restaurateurs Iván García and Gerardo Zabaleta, strangers-turned-friends of director Heidi Ewing, a documentary filmmaker by training. The 2020 film first premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, where it won the NEXT Innovator and Audience Awards.

Nostalgia was a crucial element for the film, a poignant feeling for those unable to return.

“Sometimes I dream about when I was a kid in Mexico and that makes my day,” said García to The Times in 2021. “That’s all we have left, to live off our memories and our dreams.”