PPP leader discharged after hunger strike as Han expulsion timing unclear

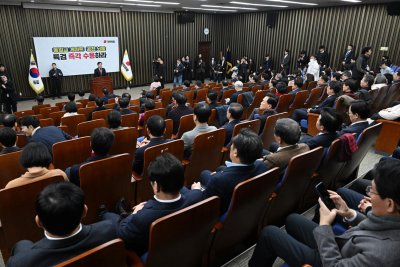

People Power Party floor leader Song Eon-seok speaks at a general meeting of lawmakers at the National Assembly in Seoul on Monday. Photo by Asia Today

Jan. 26 (Asia Today) — People Power Party leader Jang Dong-hyuk was discharged from a hospital Monday after four days of treatment following an eight-day hunger strike, but party officials said the timing of major pending decisions, including a motion to expel former party leader Han Dong-hoon, remains uncertain.

The conservative People Power Party said Jang has expressed a strong desire to return to party duties soon, but medical staff advised he needs rest and recovery. The party said Jang will continue examinations and outpatient treatment after leaving the hospital.

Jang was taken from the National Assembly hunger strike site on a stretcher Thursday and hospitalized. He had staged the hunger strike from Jan. 15 to Jan. 22, urging the Democratic Party to accept what the party calls “dual special prosecutors” to investigate allegations tied to the Unification Church and a separate nomination-related bribery case.

At a general meeting of lawmakers Monday, People Power Party floor leader Song Eon-seok called for unity as the party prepares to resume its campaign as the main opposition force. Song said the special prosecutor bills are needed to ensure “black money” does not take root, arguing no one should be exempt from scrutiny.

Even if Jang returns to party work as early as Wednesday, party leaders said it is unclear when the expulsion motion involving Han will be submitted as an agenda item. Chief spokesperson Park Sung-hoon told reporters that the motion was not on Monday’s agenda and said its timing has not been decided.

Park said the period to request a retrial in Han’s disciplinary case has passed and that Han did not submit a defense during that window, leaving the next step dependent on Jang’s decision.

Park added that Jang’s condition appears more serious than initially expected, citing cardiopulmonary symptoms and low oxygen saturation. He said further examinations, including cardiac testing, were scheduled Monday and that the disciplinary motion could be handled as early as Monday.

— Reported by Asia Today; translated by UPI

© Asia Today. Unauthorized reproduction or redistribution prohibited.

Original Korean report: https://www.asiatoday.co.kr/kn/view.php?key=20260127010012299