The Roberts court broadly expanded Trump’s power in 2025, with these key exceptions

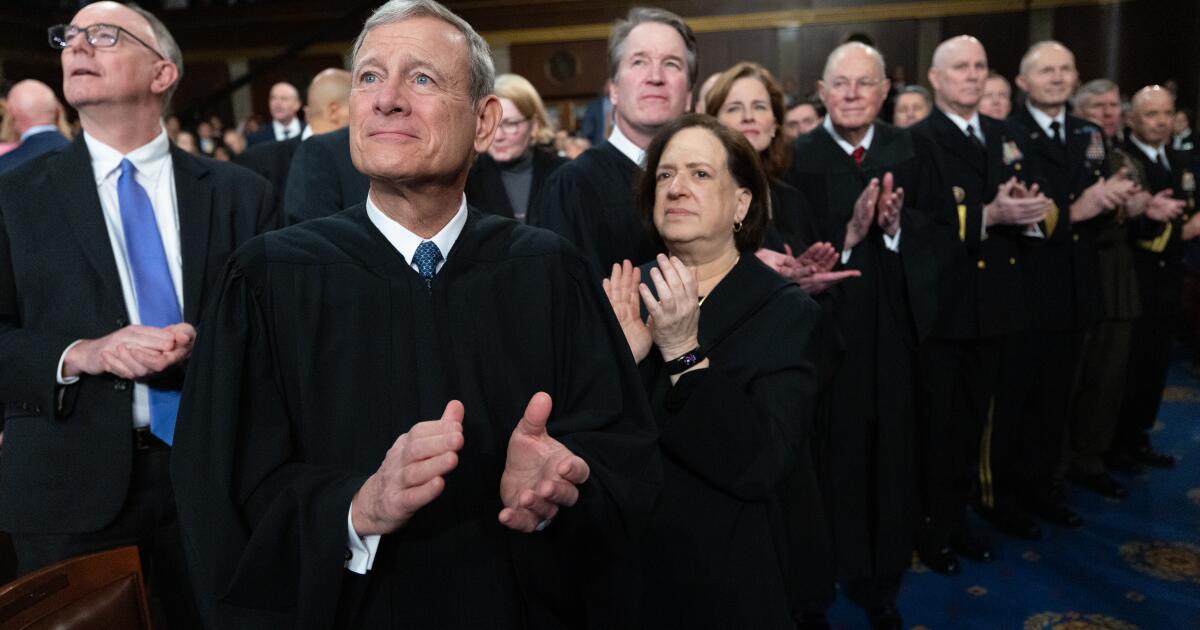

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., ended the first year of President Trump’s second term with a record of rulings that gave him much broader power to control the federal government.

In a series of fast-track decisions, the justices granted emergency appeals and set aside rulings from district judges who blocked Trump’s orders from taking effect.

With the court’s approval, the administration dismissed thousands of federal employees, cut funding for education and health research grants, dismantled the agency that funds foreign aid and cleared the way for the U.S. military to reject transgender troops.

But the court also put two important checks on the president’s power.

In April, the court twice ruled — including in a post-midnight order — that the Trump administration could not secretly whisk immigrants out of the country without giving them a hearing before a judge.

Upon taking office, Trump claimed migrants who were alleged to belong to “foreign terrorist” gangs could be arrested as “enemy aliens” and flown secretly to a prison in El Salvador.

Roberts and the court blocked such secret deportations and said the 5th Amendment entitles immigrants, like citizens, a right to “due process of law.” Many of the arrested men had no criminal records and said they never belonged to a criminal gang.

Those who face deportation “are entitled to notice and opportunity to challenge their removal,” the justices said in Trump vs. J.G.G.

They also required the government to “facilitate” the release of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, who had been wrongly deported to El Salvador. He is now back in Maryland with his wife, but may face further criminal charges or efforts to deport him.

And last week, Roberts and the court barred Trump from deploying the National Guard in Chicago to enforce the immigration laws.

Trump had claimed he had the power to defy state governors and deploy the Guard troops in Los Angeles, Portland, Ore., Chicago and other Democratic-led states and cities.

The Supreme Court disagreed over dissents from conservative Justices Samuel A. Alito, Clarence Thomas and Neil M. Gorsuch.

For much of the year, however, Roberts and the five other conservatives were in the majority ruling for Trump. In dissent, the three liberal justices said the court should stand aside for now and defer to district judges.

In May, the court agreed that Trump could end the Biden administration’s special temporary protections extended to more than 350,000 Venezuelans as well as an additional 530,000 migrants who arrived legally from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua or Venezuela.

It was easier to explain why the new administration’s policies were cruel and disruptive rather than why they were illegal.

Trump’s lawyers argued that the law gave the president’s top immigration officials the sole power to decide on these temporary protections and that “no judicial review” was authorized.

Nonetheless, a federal judge in San Francisco twice blocked the administration’s repeal of the temporary protected status for Venezuelans, and a federal judge in Boston blocked the repeal of the entry-level parole granted to migrants under Biden.

The court is also poised to uphold the president’s power to fire officials who have been appointed for fixed terms at independent agencies.

Since 1887, when Congress created the Interstate Commerce Commission to regulate railroad rates, the government has had semi-independent boards and commissions led by a mix of Republicans and Democrats.

But Roberts and the court’s conservatives believe that because these agencies enforce the law, they come under the president’s “executive power.”

That ruling may come with an exception for the Federal Reserve Board, an independent agency whose nonpartisan stability is valued by business leaders.

Georgetown Law Professor David Cole, the former legal director at the American Civil Liberties Union, said the court has sent mixed signals.

“On the emergency docket, it has ruled consistently for the president, with some notable exceptions,” he said. “I do think it significant that it put a halt to the National Guard deployments and to the Alien Enemies Act deportations, at least for the time being. And I think by this time next year, it’s possible that the court will have overturned two of Trump’s signature initiatives — the birthright citizenship executive order and the tariffs.”

For much of 2025, the court was criticized for handing down temporary unsigned orders with little or no explanation.

That practice arose in 2017 in response to Trump’s use of executive orders to make abrupt, far-reaching changes in the law. In response, Democratic state attorneys and lawyers for progressive groups sued in friendly forums such as Seattle, San Francisco and Boston and won rulings from district judges who put Trump’s policies on hold.

The 2017 “travel ban” announced in Trump’s first week in the White House set the pattern. It suspended the entry of visitors and migrants from Venezuela and seven mostly-Muslim countries on the grounds that those countries had weak vetting procedures.

Judges blocked it from taking effect, and the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed, saying the order discriminated based on nationality.

A year later, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case and upheld Trump’s order in a 5-4 ruling. Roberts pointed out that Congress in the immigration laws clearly gave this power to the president. If he “finds that the entry of … any class of aliens … would be detrimental,” it says, he may “suspend the entry” of all such migrants for as long as “he shall deem necessary.”

Since then, Roberts and the court’s conservatives have been less willing to stand aside while federal judges hand down nationwide rulings.

Democrats saw the same problem when Biden was president.

In April 2023, a federal judge in west Texas ruled for anti-abortion advocates and decreed that the Food and Drug Administration had wrongly approved abortion pills that can end an early pregnancy. He ordered that they be removed from the market before any appeals could be heard and decided.

The Biden administration filed an emergency appeal. Two weeks later, the Supreme Court set aside the judge’s order, over dissents from Thomas and Alito.

The next year, the court heard arguments and then threw out the entire lawsuit on the grounds that abortion foes did not have standing to sue.

Since Trump returned to the White House, the court’s conservative majority has not deferred to district judges. Instead, it has repeatedly lifted injunctions that blocked Trump’s policies from taking effect.

Although these are not final rulings, they are strong signs that the administration will prevail.

But Trump’s early wins do not mean he will win on some of his most disputed policies.

In November, the justices sounded skeptical of Trump’s claim that a 1977 trade law, which did not mention tariffs, gave him the power to set these import taxes on products coming from around the world.

In the spring, the court will hear Trump’s claim that he can change the principle of birthright citizenship set in the 14th Amendment and deny citizenship it to newborns whose parents are here illegally or entered as visitors.

Rulings on both cases will be handed down by late June.