The Palisades fire discourse is stuck in January 2025

There are two, seemingly irreconcilable, stories of how the Palisades fire became a deadly and destructive behemoth dominating post-fire discourse. One is told by the residents who lived through it, and the other by the government officials who responded to it.

Government officials have routinely argued they had little agency to change the outcome of a colossal fire fanned by intense winds. Palisadians point to a string of government missteps they say clearly led to and exacerbated the disaster.

Officials’ unwillingness to acknowledge any mistakes has only sharpened residents’ focus on them, functionally bringing to a grinding halt any discourse around how the two groups can work to prevent the next disaster.

Instead, residents have been left feeling gaslighted by their own government, while fire officials struggle to navigate the backlash to new fire safety measures.

When officials and residents do talk solutions, the former tend to emphasize personal responsibility — most prominently, Zone Zero, which will require residents to remove flammable materials and plants near their homes — while the latter often push for greater government responsibility: a bolstered fire service and a beefed-up water system.

The residents’ account goes like this:

The Fire Department failed to put out the Lachman fire a week prior. Mayor Karen Bass then left the country during dangerous weather while the deputy mayor for public safety position was vacant after Brian K. Williams, who formerly held the role, was put on leave after allegedly making a bomb threat against City Hall. L.A.’s city Fire Department officials failed to deploy 1,000 firefighters in advance of the fire and did not call for firefighters to work extended hours, while dozens of fire engines were out of commission at the time, waiting for repairs.

An aircraft drops fire retardant on the Palisades fire on Jan. 8, 2025.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Meanwhile the L.A. Department of Water and Power left a water reservoir designed for firefighting empty and the city failed to analyze how it would evacuate the community.

However, when government officials — be it the mayor, the fire chief or the governor — describe the fire, they tell a different story:

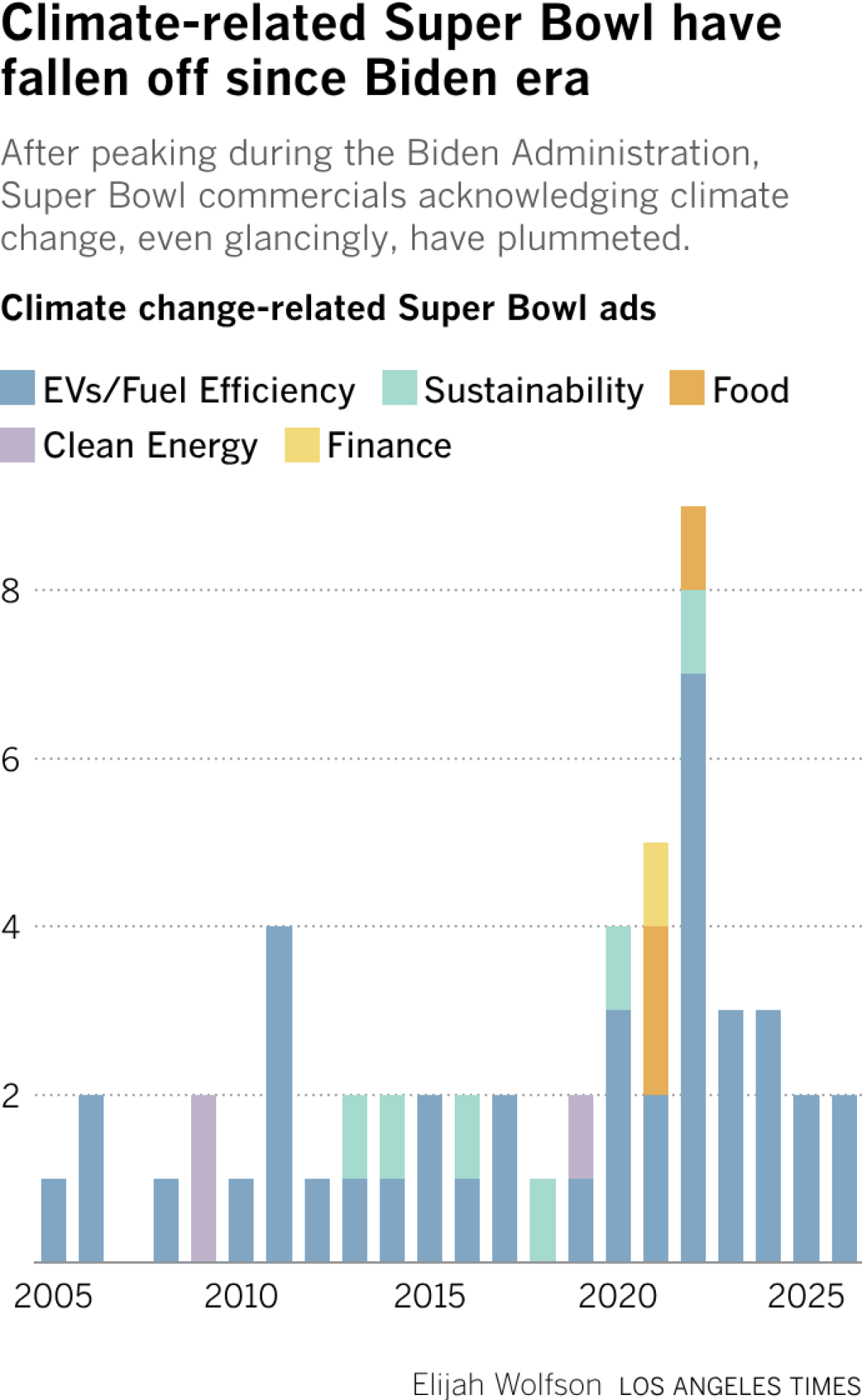

The day after the fire erupted, Bass placed some of the blame on climate change, which some scientists argue has exacerbated fires in the area by increasing the frequency and intensity of hot, dry and windy conditions. Fire officials stressed that the winds during the first few days of the fires were so strong that there was little even the best-equipped fire service could do and that the fire grew so large that there wasn’t a single fire hydrant system in the world that could handle the demand.

Many residents don’t deny that, under such extreme conditions and after the fire reached a certain scale and ferocity, the destruction became inevitable — and there are many who would just like to move on from January 2025.

However, others remain frustrated that these official versions of the story do not acknowledge the government’s failure to prepare for such conditions and its failure to stop the fire before it passed the threshold of inevitability. Indeed, at times, officials have shied away from these uncomfortable discussions to shield themselves from potential liability.

One telling example: On the one-year anniversary of the fire, residents gathered to voice these frustrations at a protest in the heart of the neighborhood. But when Bass was asked to comment on the event, she dismissed it as an unfit way to commemorate the anniversary and accused organizers of profiting off the disaster.

Survivors gathered in Palisades Village to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the Palisades fire on Jan. 7, 2026.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

This sort of dismissal has essentially forestalled any constructive discussions of climate change, the limits of the fire service and water systems and proposals like Zone Zero, since so many Palisadians now feel like any of that is just a fig leaf for the government’s agency and responsibility, and not a good faith discussion of how to solve the wildfire problem.

The reality is, how climate change is influencing wildfires in Southern California is still a subject of debate among scientists. That doesn’t mean that local leaders need to sit on their hands and wait for consensus. Experts can easily point to a litany of steps that can be taken to better protect residents, regardless of how profound the impact is of global warming on fire risk in the region.

Fire scientists and fire service veterans (who have the pleasure of speaking freely in retirement) argue both personal responsibility and government responsibility play key roles in preventing disasters:

Home hardening and defensible space slow down the dangerous chain reaction in which a wildfire jumps into an urban area and spreads from house to house. It is then the responsibility of a prepared and capable fire service to use that extra time to stop the destruction in its tracks.

The bottom line is that neither the government’s story nor the residents’ story of the Palisades fire is fundamentally wrong. And neither is fully complete.

The conversations around fire preparedness that need to happen next will require both homeowners and government officials to acknowledge they both have real agency and responsibility to shape the outcome of the next fire.

More recent wildfire news

Mayor Karen Bass personally directed the watering down of the city Fire Department’s after-action report on the Palisades fire in an attempt to limit the city’s legal liability, my colleague Alene Tchekmedyian reports. The revelations come after Bass repeatedly denied any involvement in the editing of the report to downplay failures.

Last Thursday, California Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta announced his office had opened a civil rights investigation into the fire preparations and response for the Eaton fire, looking for any potential disparities in the historically Black west Altadena, my colleague Grace Toohey reports. West Altadena received late evacuation alerts, and officials allocated limited firefighting resources to the neighborhood.

Meanwhile, the federal government is hard at work attempting to unify federal firefighting resources within the Department of the Interior — including from the Bureau of Land Management and National Park Service — into one U.S. Wildland Fire Service by the end of the year. The effort does not yet include the federal government’s largest firefighting team in the U.S. Forest Service. Because it is housed under the Department of Agriculture, not the Department of the Interior, merging it into the U.S. Wildland Fire Service would probably require congressional approval.

A few last things in climate news

An investigation from my colleague Hayley Smith found that, as Southern California’s top air pollution authority weighed a proposal to phase out gas-powered appliances, it was inundated with at least 20,000 AI-generated emails opposing the measure. When staff reached out to a subset of people listed as submitters of the comments, only five responded, with three saying they had no knowledge of the letters. The authority ultimately scrapped the proposal.

The National Science Foundation announced last week that a supercomputer in Wyoming used by thousands of scientists to simulate and research the climate would be transferred from a federally funded research institute to an unnamed “third-party operator.” It left scientists shocked and concerned.

The Department of Energy has made new nuclear energy a priority; however, no new commercial-scale nuclear facilities are currently under construction, and it’s unclear how the U.S., which imports most of the uranium used by its current reactors, would fuel any new nuclear power plants. These sorts of technical challenges have vexed nuclear advocates who are fighting against a decades-long stagnation in nuclear development, triggered primarily by safety concerns.

This is the latest edition of Boiling Point, a newsletter about climate change and the environment in the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox. And listen to our Boiling Point podcast here.

For more wildfire news, follow @nohaggerty on X and @nohaggerty.bsky.social on Bluesky.