JPMorgan reveals that it closed Trump’s accounts after Jan. 6 attack

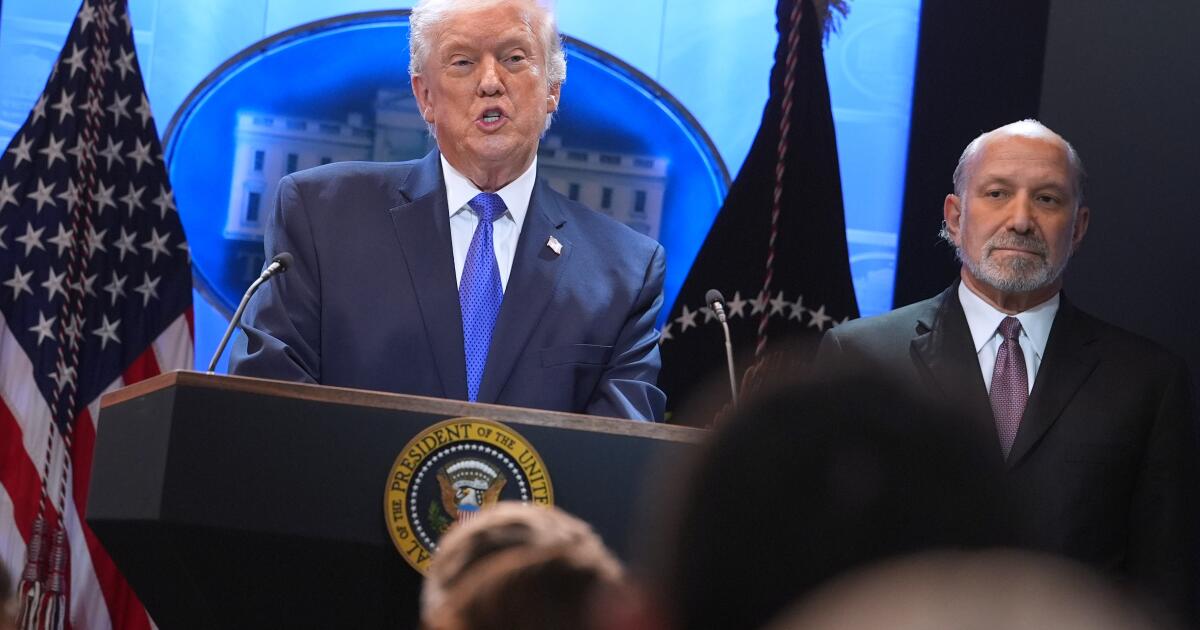

NEW YORK — JPMorgan Chase acknowledged for the first time that it closed the bank accounts of Donald Trump and several of his businesses in the aftermath of the Jan. 6, 2021, attacks on the U.S. Capitol, the latest development in a legal saga between the president and the nation’s biggest bank over the issue known as “debanking.”

The acknowledgment came in a court filing submitted this week in Trump’s lawsuit against the bank and its leader, Jamie Dimon. The president sued for $5 billion, alleging that his accounts were closed for political reasons, disrupting his business operations.

“In February 2021, JPMorgan informed Plaintiffs that certain accounts maintained with JPMorgan’s CB and PB would be closed,” JPMorgan’s former chief administrative officer Dan Wilkening wrote in the court filing. The “PB” and “CB” stands for JPMorgan’s private bank and commercial bank.

Until now, JPMorgan has never admitted it closed the president’s accounts in writing after Jan. 6. The bank would only speak hypothetically about when the bank closes accounts and its reasons for closing accounts, citing bank privacy laws.

A spokeswoman for the bank declined to comment beyond what the bank said in its legal filings.

Trump originally sued JPMorgan in Florida state court, where the president’s primary residence is now located. The filings this week are part of an effort by JPMorgan Chase to have the case moved from state to federal court and to have the jurisdiction of the case moved to New York, which is where the bank accounts were located and where Trump kept much of his business operations until recently.

Trump originally accused the bank of trade libel and violating state and federal unfair and deceptive trade practices.

In the original lawsuit, Trump said he tried to raise the issue personally with Dimon after the bank sent him notices that JPMorgan would close his accounts, and that Dimon assured Trump he would figure out what was happening. The lawsuit alleges Dimon failed to follow up with Trump.

Further, Trump’s lawyers allege that JPMorgan placed the president and his companies on a reputational “blacklist” that both JPMorgan and other banks use to keep clients from opening accounts with them in the future. The blacklist has yet to be defined by the president’s lawyers.

“If and when Plaintiffs explain what they mean by this ‘blacklist,’ JPMorgan will respond accordingly,” the bank’s lawyers said in a filing.

JPMorgan has previously said that although it regrets that Trump felt the need to sue the bank, the lawsuit has no merit.

The issue of debanking is at the center of the case. Debanking occurs when a bank closes the accounts of a customer or refuses to do business with a customer in the form of loans or other services. Once a relatively obscure issue in finance, debanking has become a politically charged issue in recent years, with conservative politicians arguing that banks have discriminated against them and their affiliated interests.

“In a devastating concession that proves President Trump’s entire claim, JPMorgan Chase admitted to unlawfully and intentionally de-banking President Trump, his family, and his businesses, causing overwhelming financial harm,” the president’s lawyers said in a statement. “President Trump is standing up for all those wrongly debanked by JPMorgan Chase and its cohorts, and will see this case to a just and proper conclusion.”

Debanking first became a national issue when conservatives accused the Obama administration of pressuring banks to stop extending services to gun stores and payday lenders under “Operation Choke Point.”

Trump and other conservative figures have alleged that banks cut them off from their accounts under the umbrella term of “reputational risk” after the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol. Trump was impeached on a charge of inciting insurrection on Jan. 6, though not convicted in the Senate; and he was criminally indicted for his role in the riot and his attempt to overturn his 2020 election defeat, but that case was dismissed after he won the 2024 election.

Since Trump came back into office, the president’s banking regulators have moved to stop any banks from using “reputational risk” as a reason for denying service to customers.

This is not the first lawsuit Trump has filed against a big bank alleging that he was debanked. The Trump Organization sued credit card giant Capital One in March 2025 for similar reasons and allegations. The case is ongoing.

Sweet writes for the Associated Press.