Why Picabo Street ‘cried all night’ before Lindsey Vonn’s final race

MILAN — There’s a lot of love in those gloves.

Before her fateful downhill run Sunday — one that ended with a violent crash after 13 seconds — Lindsey Vonn pulled on a pair of out-of-production gloves from her childhood skiing idol, Picabo Street.

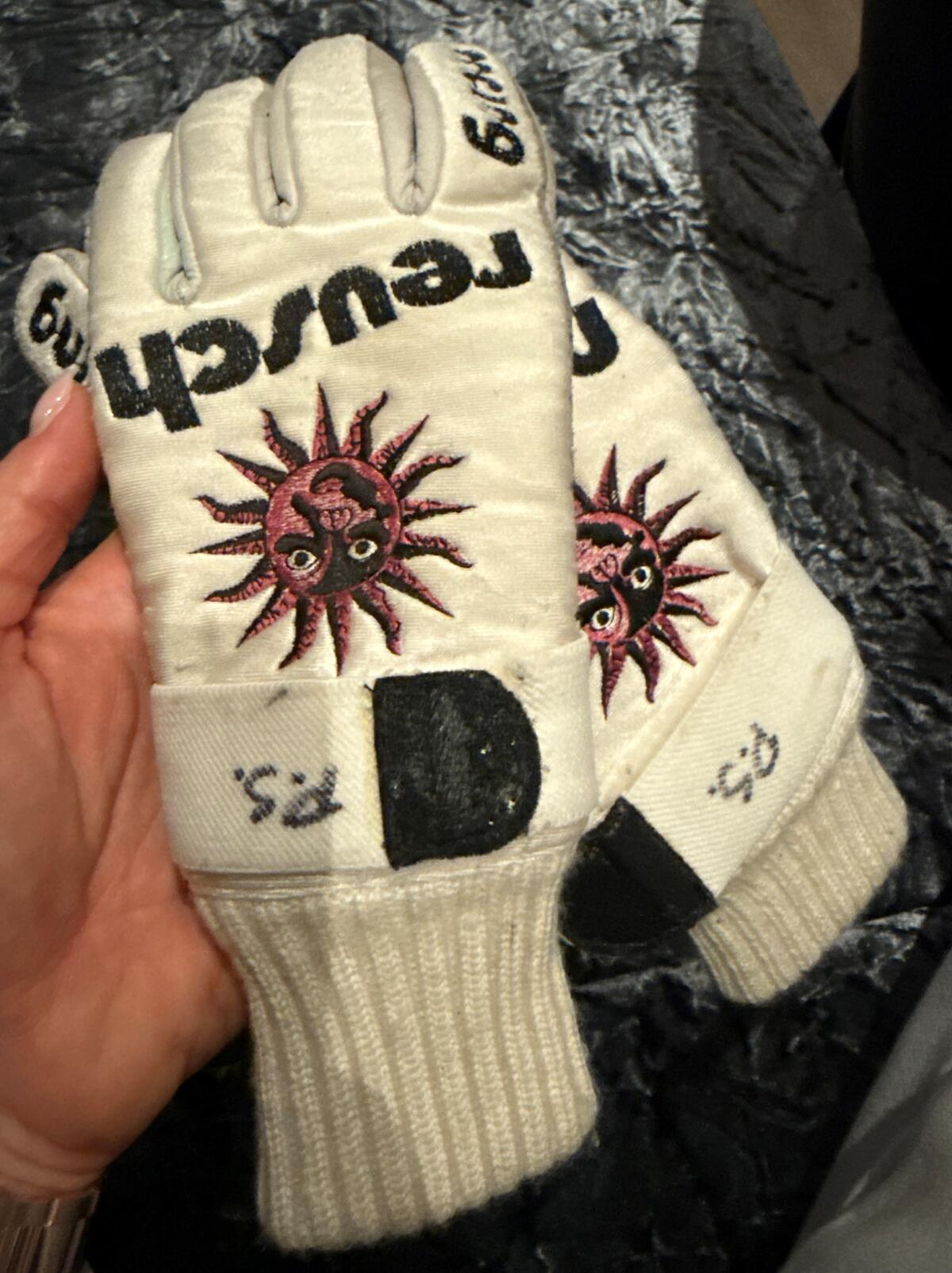

The gloves are weathered and white, their brightness dulled by the decades, with the brand name “reusch” across the knuckles and a big, plum-colored sun on top. On the wrist straps are Street’s initials, scrawled in marker.

Vonn didn’t announce the gesture, nor did NBC, which employs Street as a color commentator. Street was at the starting gate of the Olimpia delle Tofane course for Sunday’s coverage.

Street confirmed to the Los Angeles Times that the two longtime friends made the glove exchange before the Olympics.

“When she saw a picture of me in those gloves, she was like, ‘Oh, those would be cool,’” Street told the Times. “And I caught wind of it, and was like, ‘Well, I just happen to have them.’”

Those gloves are especially meaningful to Street because they are immortalized on the bronze statue of her in Sun Valley, Idaho. The sun across the top is visible in the sculpted detail.

“It was just my way of being able to show her that, you know, I love you and I believe in you,” Street said. “And wear these, they’ll be fun.”

The two were on the U.S. Ski Team together — Street at the end of her career, Vonn at the beginning — and have been close friends for years. Vonn co-produced the documentary “Picabo,” and in it tells Street, “You are my hero.”

The gloves Picabo Street gave to Lindsey Vonn before Vonn’s race in the Olympic downhill on Feb. 8.

(Courtesy of Picabo Street)

Street, whose skiing and who’s first name helped make her a pop-culture sensation during her Olympic career is a huge fan of Vonn. In speaking to the Times, she said on multiple occasions, “I’m not the story here, so this isn’t about me.”

Still, there are some uncanny coincidences. For instance, Vonn was the 13th skier in Sunday’s lineup and her run lasted 13 seconds before her fall, in which she broke her left leg. Late in her career, Street suffered a broken left leg in a race that took place on Friday the 13th in Crans Montana, Switzerland, where Vonn sustained a ruptured anterior cruciate ligament in a fall at the end of January.

Street had an emotional reaction when she learned what bib number Vonn would be wearing.

“I about puked when I saw number 13,” Street said. “I got very little sleep. I cried all night long, and I cried in the morning. I couldn’t shake it.”

She said her main concern now is her friend’s return to health, not for competitive skiing but for life.

“I want her leg to work for her,” Street said. “I want her nerves to work for her. I want her to have function of her whole body again, and in case she wants to have a family, she can play with her kids.”

The gloves weren’t the first piece of equipment Street loaned to Vonn.

Lindsey Vonn prepares to leave the downhill starting gate while wearing Picabo Street’s gloves on Feb. 8.

(Screenshot courtesy of NBC)

“I remember when I raced in Salt Lake, and I retired, and I was packed up and leaving the house we were staying in,” Street said, referring to the 2002 Winter Olympics. “She came into the house, and I remember giving her a huge hug and giving her a couple of items — one of which she wore in those Games — which was a sleeve around her braid, because we both have really long hair.

“I wore a red, white and blue American-flag neoprene sleeve around my hair, and she wore one as well. I handed her that there and was like, ‘Here you go. Go get ‘em.’”

After Vonn’s crash Sunday, Street told her own mother about loaning the gloves.

“I said, ‘Oh God, mom, she was wearing my gloves,’” she said, her voice catching with emotion.

“At first my mom said, ‘Oh, honey,’ and then she goes, ‘OK, let’s flip this. Maybe the gloves kept her from getting injured worse.’”