The 30th annual United Nations climate change conference (COP30) begins on Monday in the Brazilian city of Belem. About 50,000 people from more than 190 countries, including diplomats and climate experts, are expected to attend the 11-day meeting in the Amazon.

Delegates are expected to discuss the climate crisis and its devastating impacts, including the rising frequency of extreme weather.

Recommended Stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

The hosts have a packed agenda with 145 meetings planned to discuss the green fuel transition and global warming as well as the failure to implement past promises.

Andre Correa do Lago, president of this year’s conference, emphasised that negotiators engage in “mutirao”, a Brazilian word derived from an Indigenous word that refers to a group uniting to work on a shared task.

“Either we decide to change by choice, together, or we will be imposed change by tragedy,” do Lago wrote in his letter to negotiators on Sunday. “We can change. But we must do it together.”

What is COP?

COP is the abbreviation for the Conference of the Parties to the Convention, which refers to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), a treaty adopted in 1992 that formally acknowledged climate change as a global threat.

The treaty also enshrined the principle of “common but differentiated responsibility”, meaning that rich countries responsible for the bulk of carbon dioxide emissions should bear the greatest responsibility for solving the problem.

The UNFCCC formally went into force in 1994 and has become the basis for international deals, such as the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, designed to limit global temperature increases to about 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels by 2100 to avoid the most catastrophic effects of global warming.

The first COP summit was held in the German capital, Berlin, in 1995. The rotating presidency, now held by Brazil, sets the agenda and hosts the two-week summit, drawing global attention to climate change while trying to corral member states to agree to new climate measures.

What’s on the agenda this year?

Brazil wants to gather pledges of $25bn and attract a further $100bn from the global financial markets for a Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF), which would provide financing for biodiversity conservation, including reducing deforestation.

Brazil has also asked countries to work on realising past promises, such as COP28’s pledge to phase out fossil fuel use. Indeed, the Brazilian government’s overarching goal for this COP is “implementation” rather than setting new goals.

“Our role at COP30 is to create a roadmap for the next decade to accelerate implementation,” Ana Tonix, the chief executive of COP30, was quoted as saying in The Guardian newspaper.

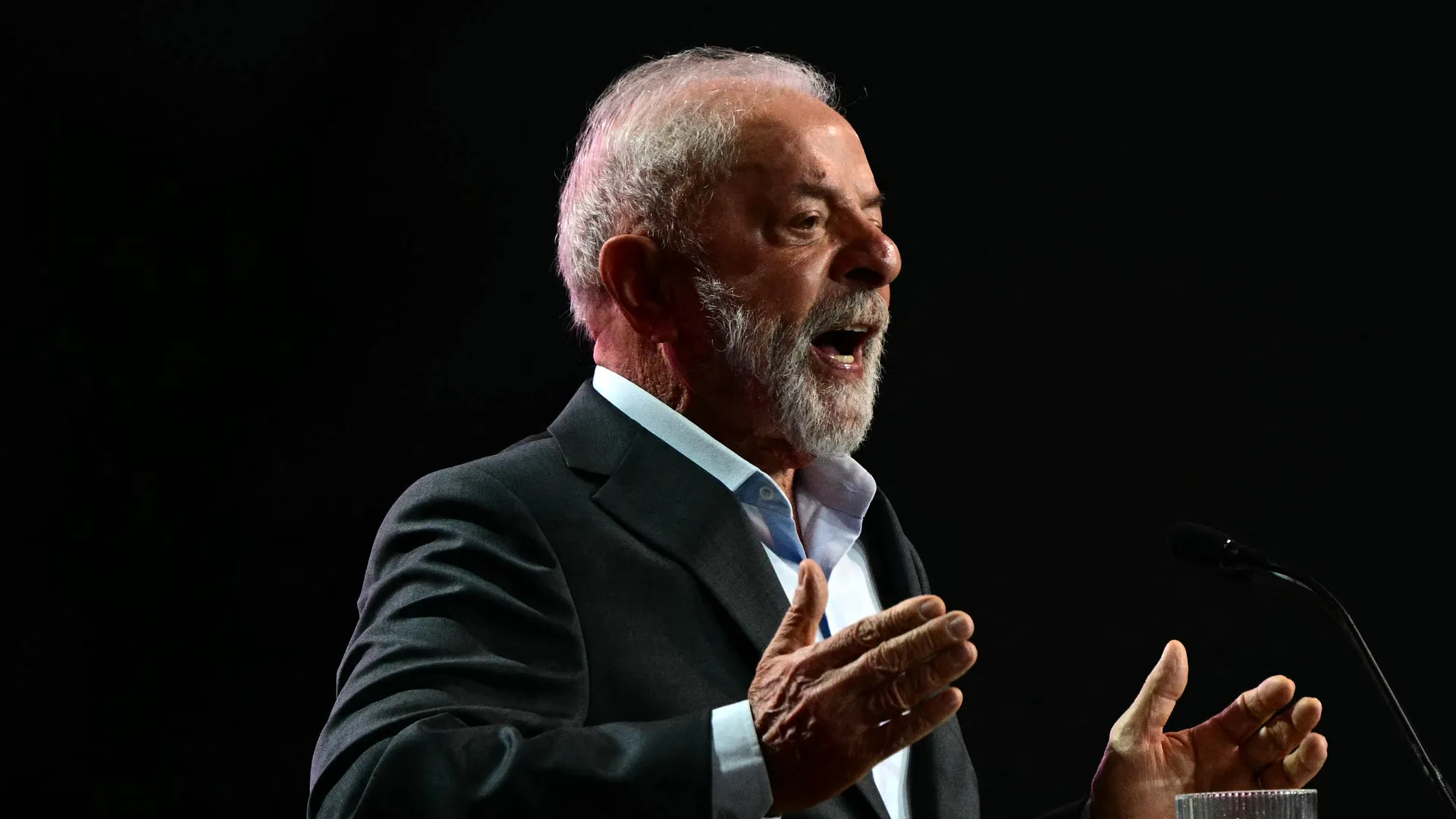

At a summit last week before COP30, Brazilian President Lula Inacio Lula da Silva said: “I am convinced that despite our difficulties and contradictions, we need roadmaps to reverse deforestation, overcome dependence on fossil fuels and mobilise the resources necessary for these objectives.”

In a letter to negotiators released late on Sunday, Simon Stiell, the UN climate chief, said the 10-year-old Paris Agreement is working to a degree “but we must accelerate in the Amazon. Devastating climate damages are happening already – from Hurricane Melissa hitting the Caribbean, super typhoons smashing Vietnam and the Philippines to a tornado ripping through southern Brazil.”

Not only must nations do more faster but they “must connect climate action to people’s real lives”, Stiell wrote.

COP30 is also the first to acknowledge the failure to so far prevent global warming.

Who will participate?

More than 50,000 people have registered to attend this year’s COP in Belem, including journalists, climate scientists, Indigenous leaders and representatives from 195 countries.

Some of the more prominent official group voices will include the Alliance of Small Island States, the G77 bloc of developing countries and the BASIC Group, consisting of Brazil, South Africa, India and China.

In September, United States President Donald Trump told the UN General Assembly that climate change was “the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world”, based on “predictions … made by stupid people”.

Trump’s aggressive approach to deny the climate crisis has further complicated the agenda at the conference, which will have no representation from Washington. Trump withdrew the US from the Paris Agreement twice – once during his first term, which was overturned by former President Joe Biden, and a second time on January 20, 2025, the day his second term began. He cited the economic burden of climate initiatives on the US. Trump has called climate change a “hoax”.

The US historically has put more heat-trapping carbon dioxide into the air from the burning of coal, oil and natural gas than any other country. On an annual basis, however, the biggest carbon polluter now is China.

COP30 organisers have been criticised for the exorbitant prices of hotel rooms in Belem, which has just 18,000 hotel beds. Brazil’s government has stepped in, offering free cabins on cruise ships to poorer nations in a last-minute bid to ensure they can attend.

As of November 1, only 149 countries had confirmed lodging. The Brazilian government said 37 were still negotiating. Meanwhile, business leaders have decamped to host their own events in the cities of Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

Brazil has also been slammed for clearing forest to build a new road to reach the conference venue.

What progress has been made since last year’s summit?

Renewables, led by solar and wind, accounted for more than 90 percent of new power capacity added worldwide last year, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency. Solar energy has now become the cheapest form of electricity in history.

Meanwhile, one in five of new cars sold around the world last year was electric, and there are now more jobs in clean energy than in fossil fuels, according to the UN.

Elsewhere, the International Energy Agency has estimated that global clean-energy investment will reach $2.2 trillion this year, which would be about twice as much as on fossil fuel spending.

At the same time, global temperatures are not just rising, they are climbing faster than ever with new records logged for 2023 and 2024. That finding was part of a study done every few years by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The new research shows the average global temperature rising at a rate of 0.27C (0.49F) each decade, almost 50 percent faster than in the 1990s and 2000s when the warming rate was around 0.2C (0.36F) per decade.

The world is now on track to cross the 1.5C threshold by 2030, after which scientists warn that humanity will trigger irreversible climate impacts. Already, the planet has warmed by 1.3C (2.34F) since the pre-industrial era, according to the World Meteorological Organization.

At the same time, governments around the world spend about $1 trillion each year subsidising fossil fuels.

At a preparatory summit with dozens of heads of state and government, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said: “The hard truth is that we have failed to ensure we remain below 1.5 degrees.”

“Science now tells us that a temporary overshoot beyond the 1.5 limit – starting at the latest in the early 2030s – is inevitable. We need a paradigm shift to limit this overshoot’s magnitude and duration and quickly drive it down,” he said on Thursday.

“Even a temporary overshoot will have dramatic consequences. It could push ecosystems past irreversible tipping points, expose billions to unliveable conditions and amplify threats to peace and security.”

How did climate change affect the world in 2025?

The India-Pakistan heatwave began unusually early, in April this year. By June, temperatures had reached a peak of about 48C (118.4F) in the Indian state of Rajasthan. Hundreds of lives were lost, and crops were decimated.

Europe also faced extreme heat this year. Over the summer, the region endured a heatwave that pushed cities like Lisbon past 46C (114.8F). In London, a prolonged period of elevated temperatures in late June caused an estimated excess 260 deaths.

At the same time, Mediterranean wildfires ravaged large tracts of Southern Europe with more than 100,000 people evacuated and dozens of deaths.

Turkiye suffered one of its worst droughts in decades, hitting agricultural areas. Rainfall dropped by up to 71 percent in some areas compared with the previous year, stressing ecosystems and energy and food production.