Bob Weir, founding member of the Grateful Dead, dies at 78

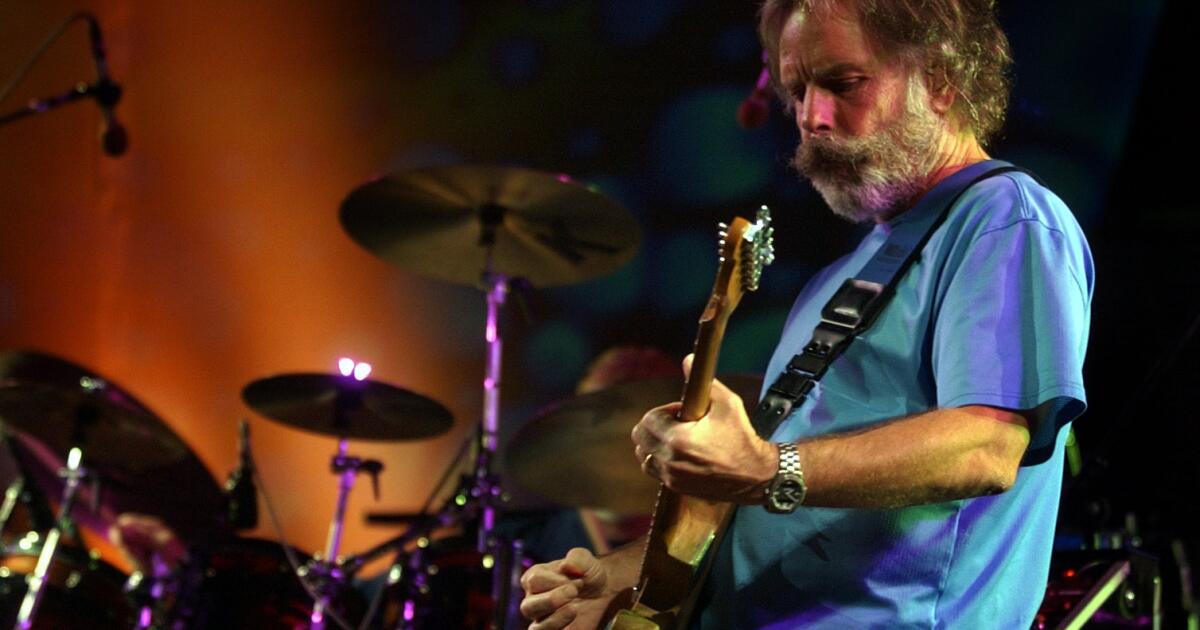

Bob Weir, a founding member of countercultural icons the Grateful Dead, known for his singular guitar playing, emotive singing and vibrant songwriting, has died at 78.

“It is with profound sadness that we share the passing of Bobby Weir,” a spokesperson for the musician confirmed to The Times. “He transitioned peacefully, surrounded by loved ones, after courageously beating cancer as only Bobby could. Unfortunately, he succumbed to underlying lung issues.”

Weir was diagnosed with cancer in July.

Weir-penned songs include Grateful Dead fan favorites “Sugar Magnolia,” “Jack Straw,” “Playing in the Band” and “Weather Report Suite.” His vocal performance on the rock-radio staple “Truckin’” counts among the band’s finest recorded moments.

The Dead released 13 studio albums with Weir, among them “Aoxomoxoa” (1969), “Workingman’s Dead” (1970), “American Beauty” (1970), “Wake of the Flood” (1973), “Terrapin Station” (1977) and 1987’s “In the Dark,” which featured the Top 10 single “Touch of Grey” and became the band’s highest-charting album, reaching No. 6 on the Billboard 200.

The Dead also released eight “official” live albums, as well as a long-running series of curated live shows known as Dick’s Picks and, later, Dave’s Picks. The band was the first to sanction fan taping at their concerts, spawning an abundance of homespun recordings that have been collected, traded and debated for decades.

Weir’s official role in the Grateful Dead was rhythm guitarist, alongside lead guitarist Jerry Garcia, but his complex style — marked by unique chord voicings, precise rhythms and a willingness to play through his bandmates instead of over them — elevated him from the standard rhythm player. “Bob’s approach to guitar playing is sort of like Bill Evans’ approach to piano was. He’s a total savant,” John Mayer told Guitar World magazine in 2017. “His take on guitar chords and comping is so original, it’s almost too original to be fully appreciated until you get deep down into what he’s doing. I think he’s invented his own vocabulary. … It’s a joyous thing to play along with.”

Weir’s first solo album, “Ace,” released in 1972, contained many songs that became standards in the Dead’s live show, including “Black-Throated Wind,” “Cassidy” and “Mexicali Blues.” “Blue Mountain,” Weir’s solo album from 2016, written in collaboration with musicians Josh Ritter and Josh Kaufman and inspired by Weir’s affinity for cowboy music and western iconography, became his highest-charting solo album, reaching No. 14 on the Billboard 200.

Weir also played in numerous side projects, post-Dead tribute acts and other rock bands, including Bob Weir & Wolf Bros, RatDog, Kingfish, Bobby and the Midnites, and the Weir, Robinson & Green Acoustic Trio with members of the Black Crowes. Dead & Company, featuring Weir, Dead bandmates Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann, bassist Oteil Burbridge, keyboardist Jeff Chimenti and singer-guitarist Mayer, kickstarted a Deadaissance in 2015, reviving the band’s music and tie-dye-wearing, hacky-sack-kicking aesthetic for legions of new and existing fans. The band’s final tour before an indefinite hiatus, in 2023, drew nearly 1 million people.

Weir also was a dedicated collaborator, inviting friends to perform with him or guesting on their records or in concert. Willie Nelson, Joan Baez, the Allman Brothers, Sammy Hagar, Nancy Wilson, Stephen Marley, Billy Strings, Tyler Childers, Sturgill Simpson, the National, Margo Price and nouveau jam act Goose counted among his many musical compatriots. “Music is like transcendental medication and Bob Weir is my spirit guide,” Price said on Instagram in 2022. Weir’s friendship with the itinerant folk singer Ramblin’ Jack Elliott began in the early 1960s, and in the new millennium, Elliott and Weir frequently performed low-key shows together in Marin County, where both resided.

Robert Hall Weir was born Oct. 16, 1947, in San Francisco to John Parber and Phyllis Inskeep, a college student who later gave him up for adoption. He was raised by adoptive parents Frederic Utter Weir and Eleanor (née Cramer) Weir in Atherton, Calif. Weir struggled as a child due to undiagnosed dyslexia and was kicked out of every school he attended, including the private Fountain Valley School in Colorado Springs, Colo., where he met John Perry Barlow, who would later contribute lyrics to the Grateful Dead.

Weir met Garcia on New Year’s Eve, 1963, at a Palo Alto music store, and soon formed the jug band Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions with Garcia and future Dead bandmate Ron “Pigpen” McKernan. Weir was just 16 years old. “There was some tension at home because I was neglecting my studies, and I grew up under the shadow of Hoover Tower,” Weir explained in an interview with Dan Rather. “My folks had Stanford in mind for me, not an itinerant troubadour. But they could also clearly see that I was following my bliss.”

About a year later, at McKernan’s urging, the trio, along with bassist Dana Morgan Jr. and drummer Kreutzmann, formed the Warlocks, an electric rock band, and played a handful of gigs before bassist Phil Lesh replaced Morgan. The group quickly discovered that a band called the Warlocks already existed and renamed themselves the Grateful Dead, a term Garcia found in a dictionary. Dead lyricist Robert Hunter and second drummer Hart joined the group in 1967.

As a member of the Dead, Weir was a kind of shape-shifting clairvoyant, creating ever-evolving sounds and forms that became essential to the fabric of American music culture. With the Dead, Weir was part of Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests in the mid-’60s, centered around experiments with LSD, and the band’s members were known to use nitrous oxide, marijuana, speed and heroin. The late ’70s launched an evident association with cocaine, and a period known as Disco Dead.

The band’s predilection for live improvisation, in which they refashioned and extended their songs via intuitive jams and imaginative transitions, drew legions of adoring fans — called Deadheads — who followed the band from city to city, and were the bedrock of the jam band movement that followed in the 1980s. The Dead’s graphic symbols, including “dancing” bears, the “Stealie” lightning skull and instrument-wielding terrapins, were plastered across innumerable merchandise and became a calling card of hippie-influenced counterculture over the ensuing decades.

Throughout the Dead’s existence, Weir was sometimes viewed as “the Other One” due to Garcia’s outsize presence in the band. Weir was its youngest member, and its most handsome. (Beautiful Bobby and the ugly brothers, the band used to joke.) He wrote and sang fewer songs than Garcia. But for others, Weir’s deference to Garcia — how he constructed a singular form of rhythm guitar playing to suit Garcia’s natural style, and used his deeper voice as a rich vocal counterpoint — was indicative of his generosity and willingness to put ego aside. In the 2014 documentary “The Other One: The Long Strange Trip of Bob Weir,” he said that he takes no pride in what he’s accomplished because he views pride as a “suspect emotion.”

Unlike his bandmates in the Dead, Weir had a long-running interest in personal style, and frequently opted for tucked-in button-down shirts, western wear and polo shirts instead of tie-dye and ponchos. “I just wanted to be kind of elegant,” he told GQ in 2019. “People were paying good money to see us, and at that time I figured that meant we ought to dress up a bit.” His denim cutoffs, which crept up in length over the years, were known as Bobby Shorts. Weir would grow his gray hair and beard into a style resembling actor Sam Elliott in the 1979 western “The Sacketts,” and began a collaboration with fashion designer James Perse that landed somewhere between cowboy and surfer.

Weir was single for most of his time in the Dead, and didn’t marry until 1999. With wife Natascha Münter, he had two daughters, Shala Monet Weir and Chloe Kaelia Weir. He was vegetarian for much of his life, and was passionate about animal rights, environmental causes and funding for the arts.

In interviews, Weir spoke of Eastern religion and philosophy, and his dreams, which dictated many decisions he made in his life. He frequently said in interviews that his relationship with Garcia never died, even after the Grateful Dead leader passed away in 1995. In 2012, Weir told Rolling Stone that Garcia “lives and breathes in me.”

“I see him in my dreams all the time,” he told the Huffington Post in 2014. “I would say I can’t talk to him, but I can. I don’t miss him. He’s here. He’s with me.”

Times staff writer Carlos De Loera contributed to this report.