A Compton family endured two killings in just eight months. Why justice is so elusive

Jessica Carter is tired of being resilient.

After her brother, Richard Ware, 48, was stabbed to death outside a Los Feliz homeless shelter last month, it fell to her to hold their extended family together.

Just eight months prior, another relative — her 36-year-old nephew, Jesse Darjean — was gunned down around the block from his childhood home in Compton. His slaying remains unsolved.

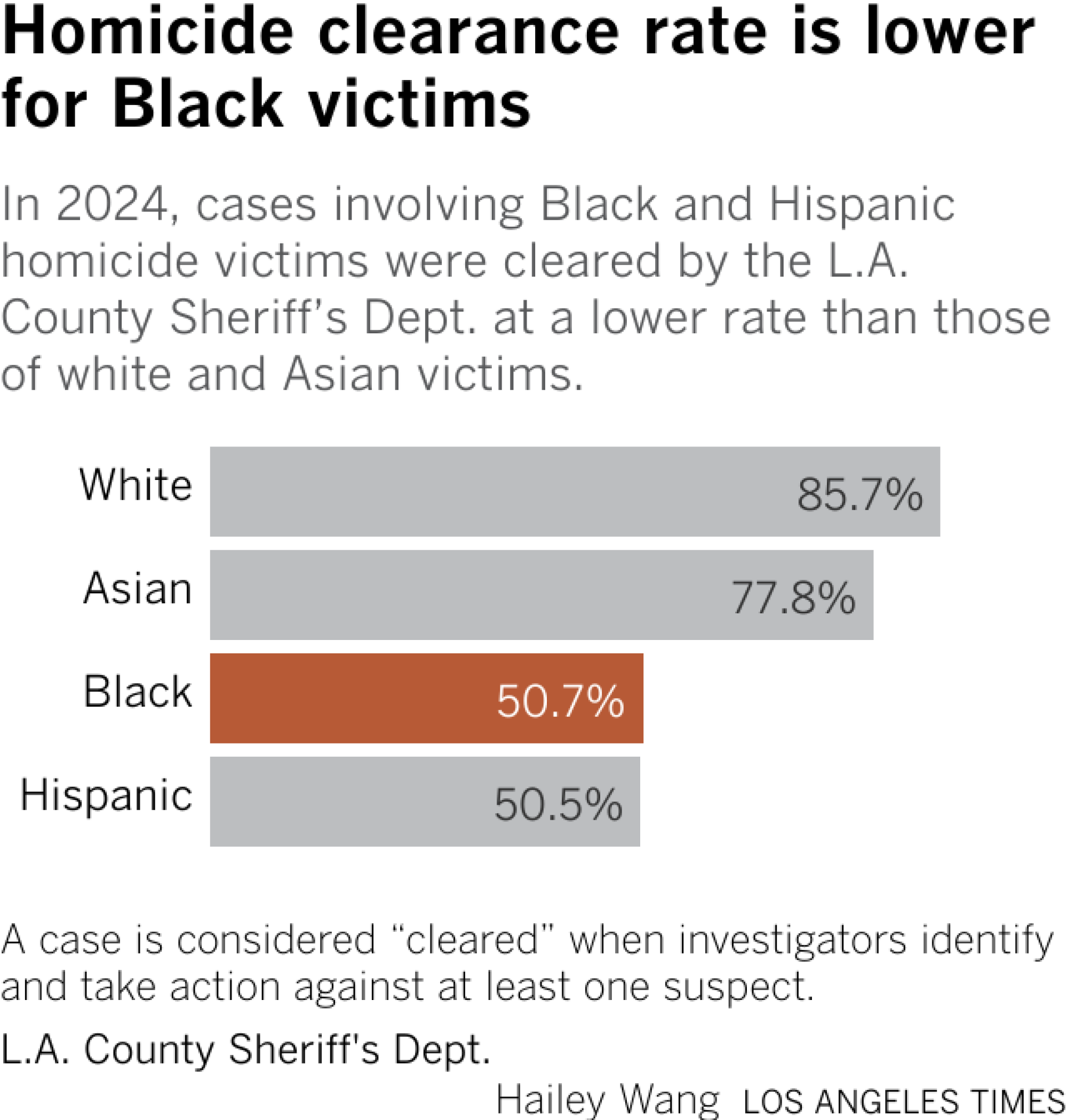

Across L.A. County and around the country, murder rates are falling to lows not seen since the late 1960s. Yet clearance rates — a measure of how often police solve cases — have remained relatively steady. In other words: Even with fewer homicides to investigate, authorities have been unable to bring more murderers to justice. Police data show killings of Black and Latino people are still less likely to be solved than those of white or Asian victims.

Carter’s hometown of Compton is still crawling out from under its reputation as a national epicenter for gang violence. But for all of its continued struggles, violent crime — especially killings — has plummeted. When the gang wars peaked in 1991, there were 87 homicides. Last year, there were 18, including Darjean’s fatal shooting on Oct. 24.

The way Carter sees it, the killers who took her brother and nephew are both getting away with it — but for different reasons. In Darjean’s shooting, there are no known suspects, witnesses or motive. But the man who stabbed Ware is known to authorities. The L.A. County district attorney’s office declined to file charges against him, finding evidence of self-defense, according to a memo released to The Times.

Ware’s sister and other relatives dispute the D.A.’s decision, claiming authorities have failed to fully investigate.

“The system failed him,” Carter said.

In the absence of arrests and charges, Carter and her family have simmered with rage, grief and frustration. With digital footprints, DNA testing and more resources than ever available to police, how is it that the people who took their loved ones are still walking free?

Jessica Carter, right, lights candles on the sidewalk to memorialize her brother, Richard Ware, who was stabbed to death outside a nearby homeless shelter.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

In Darjean’s case, the investigation is led by the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department, which has patrolled Compton since 2000, when the city disbanded its own Police Department. Leads appear to be scarce. His body was found in the back seat of his car, which had been riddled with bullets. A father of three, he had just gotten home late at night from one of his jobs as a security guard.

To Sherrina Lewis, his mother, it seemed the world was quick to forget and move on. News outlets largely ignored the shooting. Social media sensationalized it. She couldn’t resist reading some of the comments online, speculating about whether her son was killed by someone he knew or because of his race or a gang affiliation.

But, Darjean was no gangster, she says. True, there had been rumors around the neighborhood about escalating conflict between the Cedar Block Pirus, a Black gang, and their Latino rivals. But if anything, Lewis said, her son was targeted in a classic case of wrong place, wrong time.

Jesse Darjean in an undated photo.

(Jessica Carter)

When homicide detectives began knocking on doors for answers, her former neighbors claimed not to have seen anything. For Lewis, it felt like betrayal — many of those neighbors had watched Darjean grow up with their kids.

“Each and every day I have to ask God to lift the hardness in my heart, because I‘m angry,” Lewis said. “They’re not gonna make my son no cold case, I promise you that.”

Lewis nearly lost Darjean once before, at the moment of his birth.

He and his twin brother were born three months early, and doctors warned that Darjean was the less likely of the two to survive. He suffered from respiratory problems, which left him dependent on a breathing machine. The prognosis was bleak.

Casha, left, and her brother Jesse Darjean as babies.

(Jessica Carter)

Doctors asked her for “a name for his death certificate” in case he died en route to a hospital in Long Beach. Picking “Jesse” on the spot was agony, she said. In the end, Darjean was the twin who survived.

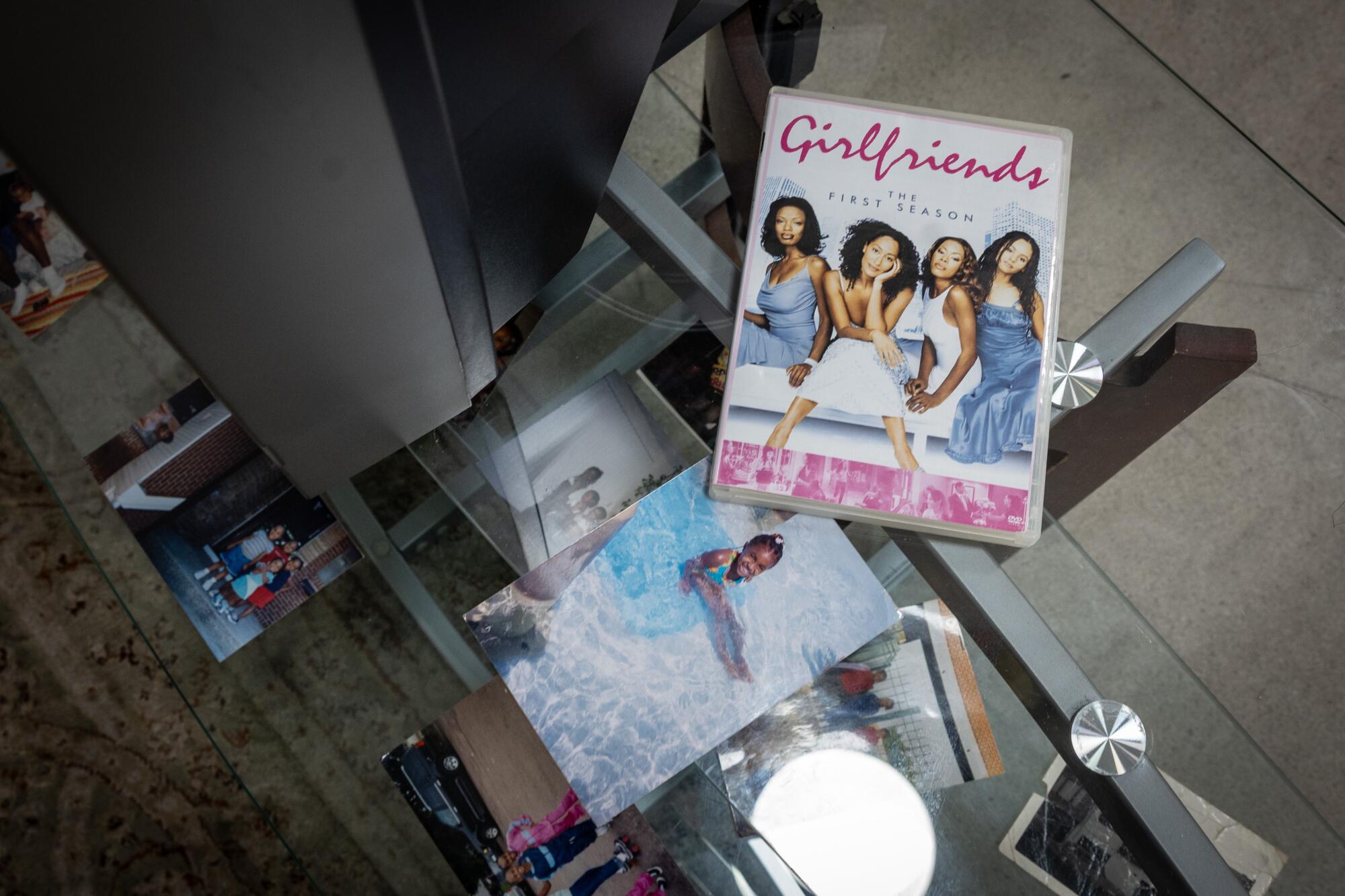

Shy as a child, he had grown up to be outgoing and witty, a person who loved to cook soul food and make dance videos with his sister and post them on Instagram. While his siblings all moved away as they got older, Darjean insisted on staying put. Compton was home, through and through, he used to tell his mother. He wasn’t blind to the gang violence, but he came to know a different side of the city, one that represented Black joy and resilience — a side he saw captured in Kendrick Lamar’s music video for the Grammy-winning “Not Like Us.”

When his niece ran for Miss Teen Compton, Darjean advocated on her behalf by taking out a full-page ad in the local newspaper that proclaimed: “Compton is the best city on Earth.”

But Darjean knew the pain of losing loved ones. His friend Montae Talbert was killed late one night in 2011 in a drive-by shooting outside an Inglewood liquor store. Talbert, known as M-Bone, was a member of the rap group Cali Swag District, the group behind the viral rap dance the “Dougie.”

Around the same time, the mother of Darjean’s oldest daughter was gunned down in Compton. A few years later, another uncle, Terry Carter, a businessman who built classic lowrider cars and started a record label with Ice Cube, was struck and killed by a vehicle driven by rap impresario Marion “Suge” Knight.

After Darjean’s funeral, which Lewis said drew more than 1,000 people, she returned to the scene of the shooting: Brazil Street, right off Wilmington Avenue, on a modest block of stucco and wood-frame homes.

With the bravado of an angry, grieving mother, she began going door-to-door in her old neighborhood, seeking answers. She wanted to show anyone who was watching that she wouldn’t be intimidated into silence.

When she confronted one of Darjean’s close childhood friends about what happened, he swore he didn’t know anything. She didn’t believe him.

“He just broke down crying. I can tell it was eating him up,” Lewis said.

The L.A. County Sheriff’s Department did not respond to multiple inquires about Darjean’s case.

Jesse Darjean holds his daughter Jessica. At right is another relative.

(Jessica Carter)

On some level, Lewis understands the hesitancy. Fear of gang retaliation and distrust of law enforcement still hangs over the west Compton neighborhood. After raising her six children there, in 2006 she sold their family home of 50 years and moved to Palmdale because she didn’t want her “kids to become accustomed to death.” For her, she said, the final straw was the discovery of a body “propped up” on her neighbor’s fence.

Like generations of Black women before her, Lewis is faced with enormous pressure to carry their family’s burden. Possessing a superhuman-like will to overcome adversity is celebrated by society with terms such as “Black Girl Magic” and “Strong Black Woman,” said Keisha Bentley-Edwards, an associate professor of medicine at Duke University. But such unrealistic expectations not only strip Black women of their innocence from an early age, but also contribute to higher pregnancy-related death rates and other bad health outcomes, she said.

“A lot of times people expect Black women to take care of it,” Bentley-Edwards said in an interview. Instead of romanticizing the struggle, she said, there should be “tangible support like housing or employment” and other resources.

But experts say safety nets are at risk, particularly after the Trump administration in April terminated roughly $811 million in public safety grants for L.A. and other major cities. As a result, federal funds for victim services programs, which offer counseling and other resources, have been slashed.

Lewis never thought she’d be in a position to need such help.

“The funny thing is, we’re from Compton born and raised, but we were not a statistic until my son was murdered,” she said. “My kids had a two-parent household. We both had jobs. We weren’t doing welfare: I worked every day.”

Months of waiting on an arrest in Darjean’s death led Carter, his aunt, into a “dark place.” She ended up taking a spiritual retreat into the mountains of Nigeria.

She was still working through the feelings of anger and guilt when she learned her brother, Ware, had been fatally stabbed on July 5.

She described the days and weeks that followed as a teary blur. Coming from a family of nurses taught her how to push aside her own grief and forge on, but she was left wondering how much more she could endure.

Ware, who went by Duke, was his family’s unofficial historian, setting out to map out their sprawling Portuguese and Creole roots and scouring the internet for long-lost relatives. He used to brag all the time about his daughter, who had graduated from nursing school and moved back to the L.A. area to work at a pediatric intensive care unit on the Westside. He used to joke that for all of his shortcomings as a father, he had at least gotten one thing right.

In recent months, though, Ware’s life had started to spiral. His diabetes had gotten worse, and a back injury left him unable to continue in his job as a long-haul truck driver. Relatives worried he was hiding a drug addiction from them.

He had adopted a bull mastiff puppy named Nala. She used to follow him everywhere, usually trotting a few steps behind without a leash. Even when he was having trouble making ends meet, he always “spoiled her,” his family said.

For a few months, he lived out of a van one of his sisters bought for him. He then landed at a shelter, a hangar-style structure on the edge of Griffith Park. He and Nala were kicked out after a short time, but he still frequented the area, and it’s where L.A. County authorities said the fight that ended in his killing began.

Prosecutors said in a memo that surveillance video showed Ware and his dog chasing another man into a parking lot across the street from the shelter. The two men, the D.A.’s memo said, had been involved in an ongoing dispute, possibly over a woman.

Friends, family and supporters of Richard Ware gather near the shelter where he was stabbed to death.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

According to the memo, the man said he’d been carrying a knife because of a previous altercation in which Ware ordered his dog to attack. On the day of the stabbing, the man said, Ware had shown up with Nala at the shelter, looking for a confrontation.

After the fight, responding officers found Ware suffering from a deep wound to his chest, Nala with several lacerations and the suspect hiding in a nearby porta-potty. His clothes had been torn off, and he was bleeding profusely from several severe dog bites, the memo said. Prosecutors said witnesses corroborated the man’s story that Ware had been the aggressor, in addition to the video footage.

Ware’s family says that account contradicts what they heard from other residents, who claimed Ware was the one defending himself after the other man attacked him with a vodka bottle. In the meantime, they are working to secure Nala’s release from the pound, where she has been nursing her injuries.

Richard Ware, 48, was stabbed to death on July 5 outside a Los Feliz homeless shelter.

(Jessica Carter)

On July 8, Carter organized a candlelight vigil for her brother outside the shelter where the killing happened. That morning, she said, she cried in the shower before steeling herself so she could run out to a Dollar Tree store to pick up some balloons.

When she got to the vigil, Lewis made her way around, greeting the swarm of relatives holding homemade signs and chanting Ware’s name. After a final prayer, the group released balloons, most of which floated upward with the evening’s lazy breeze. Some, though, got caught in the branches of a large tree nearby.

A smile finally crossed Carter’s face as she pointed up to them. She took it as a sign from Ware, as though he was saying a last goodbye before he departed to heaven.

“He’s trying to hang on,” she said.