Supreme Court will hear Trump’s plan to restrict birthright citizenship

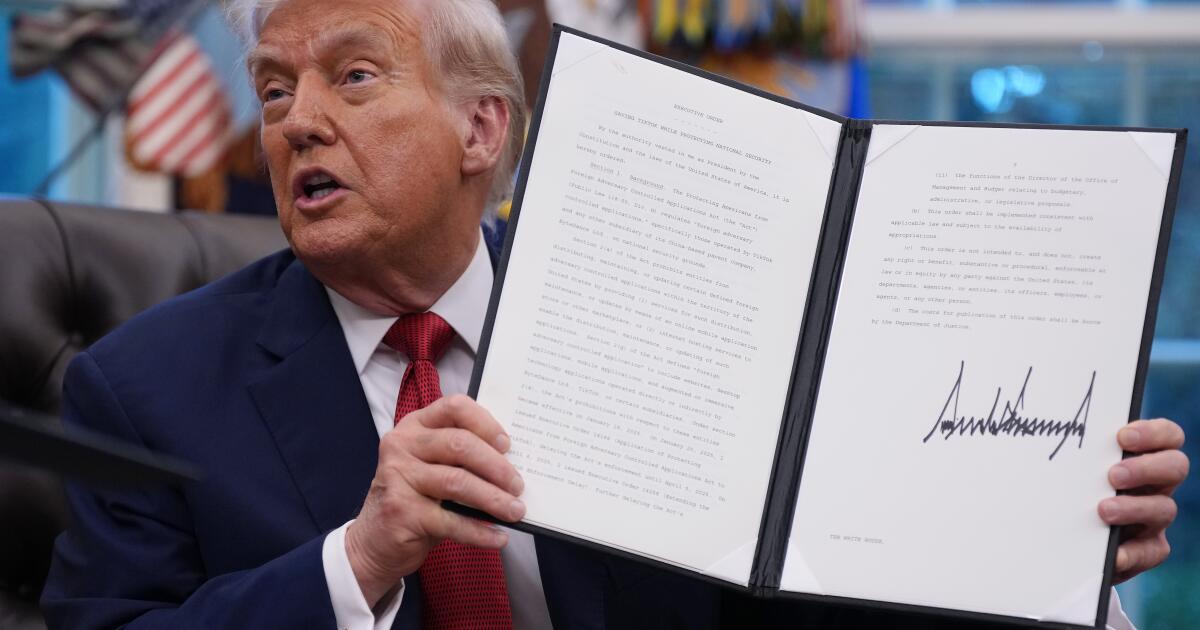

WASHINGTON — President Trump’s plan to end birthright citizenship for newborns whose parents are here illegally or temporarily will get a full hearing before the Supreme Court.

The justices agreed Friday to hear arguments on Trump’s proposal after judges across the nation had declared it unconstitutional and blocked it from taking effect.

Trump’s lawyers contended the government had been misreading the 14th Amendment for at least a century.

He proposed a change because “the President recognized that automatic citizenship for children of illegal aliens operates as a powerful incentive for illegal migration,” they told the court.

“Not only do such children automatically become full citizens, but their citizenship is often promptly asserted to impede the removal of their illegal-alien parents,” argued Solicitor Gen. J. Dean Sauer.

The 14th Amendment of 1868 begins with the words, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof are citizens of the United States and the state wherein they reside.”

The amendment formally overturned the Dred Scott decision in which the court had said that free Black people were not citizens.

The key phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” has been understood to mean “subject to the laws” of the United States,” and that includes nearly everyone here except foreign diplomats.

But Trump’s lawyers argued that the phrase was understood in 1868 to refer more narrowly to persons who had a political allegiance to the United States, rather than to a foreign country.

Based on that understanding, Trump’s lawyer contended the “Citizenship Clause was adopted to grant citizenship to freed slaves and their children, not to the children of illegal aliens, birth tourists, and temporary visitors.”

He said “near-automatic citizenship has spawned an industry of modern ‘birth tourism,’ by which foreigners travel to the United States solely for the purpose of giving birth here and obtaining citizenship for their children.”

In rejecting Trump’s proposal, lawyers and judges have pointed to the Supreme Court’s 1898 ruling in favor of Wong Kim Ark. He was born in San Francisco to Chinese parents and later had his citizenship confirmed by the court.

“No president can change the 14th Amendment’s fundamental promise of citizenship,” said Cecillia Wang, ACLU national legal director. “For over 150 years, it has been the law and our national tradition that everyone born on U.S. soil is a citizen from birth. … We look forward to putting this issue to rest once and for all in the Supreme Court this term.”

Trump’s lawyers waved aside that precedent by arguing that Wong Kim Ark’s parents were “permanently domiciled” in California. He said the court’s opinion repeatedly referred to that fact, suggesting that birthright citizenship was limited to parents who were legal residents, not those who were here illegally or temporarily.

The court will likely hear arguments in the case of Trump v. Barbara in March and issue a ruling by late June.

If the court were to uphold Trump’s proposal, it would operate “on a prospective basis only,” Sauer said.

It would deny citizenship to babies whose mother or father is neither a citizen nor “lawful permanent resident,” and it would exclude children of mothers who were “visiting on a student, work or tourist visa.”