Who are Bangladesh’s new cabinet members? | Bangladesh Election 2026 News

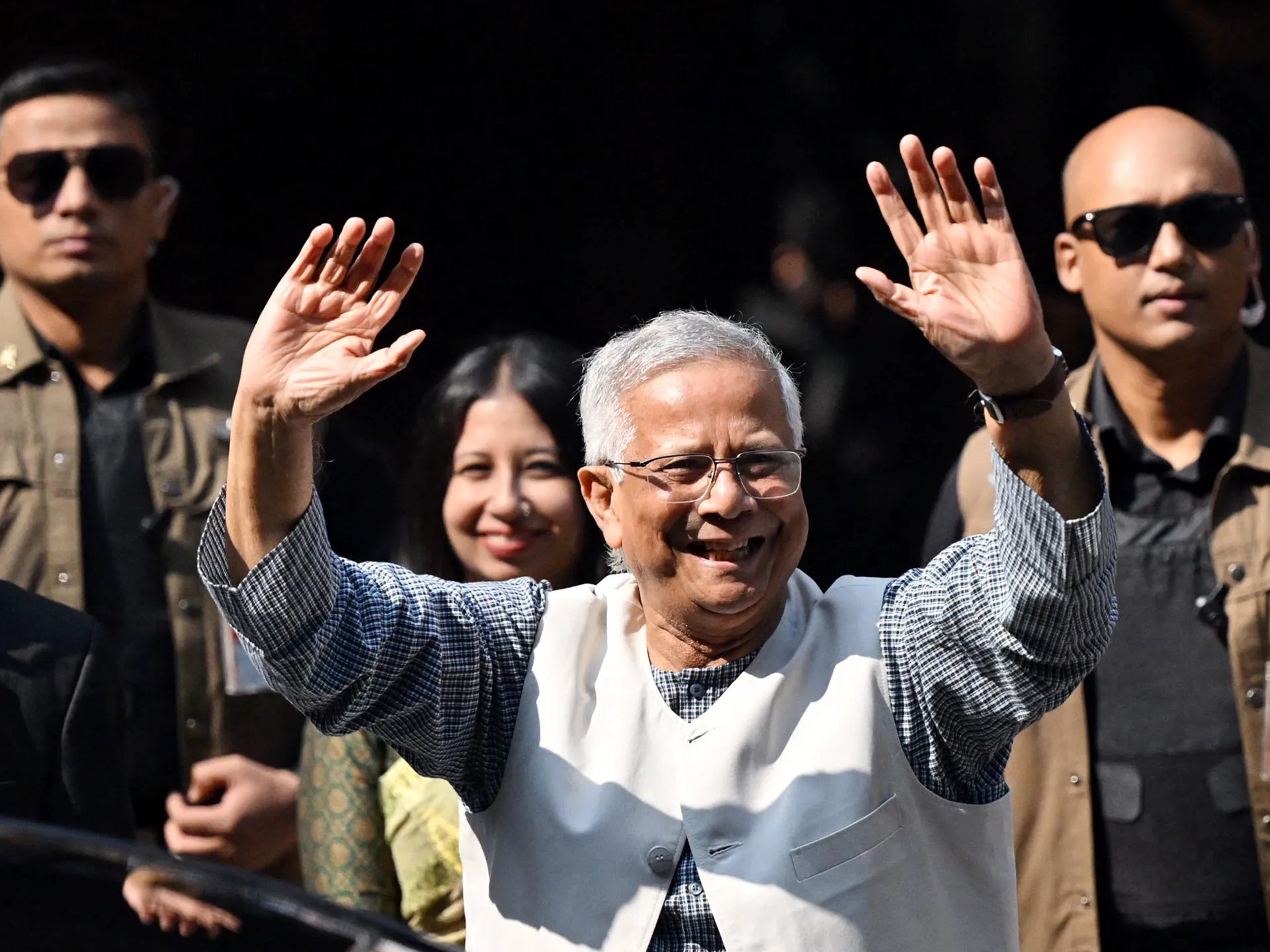

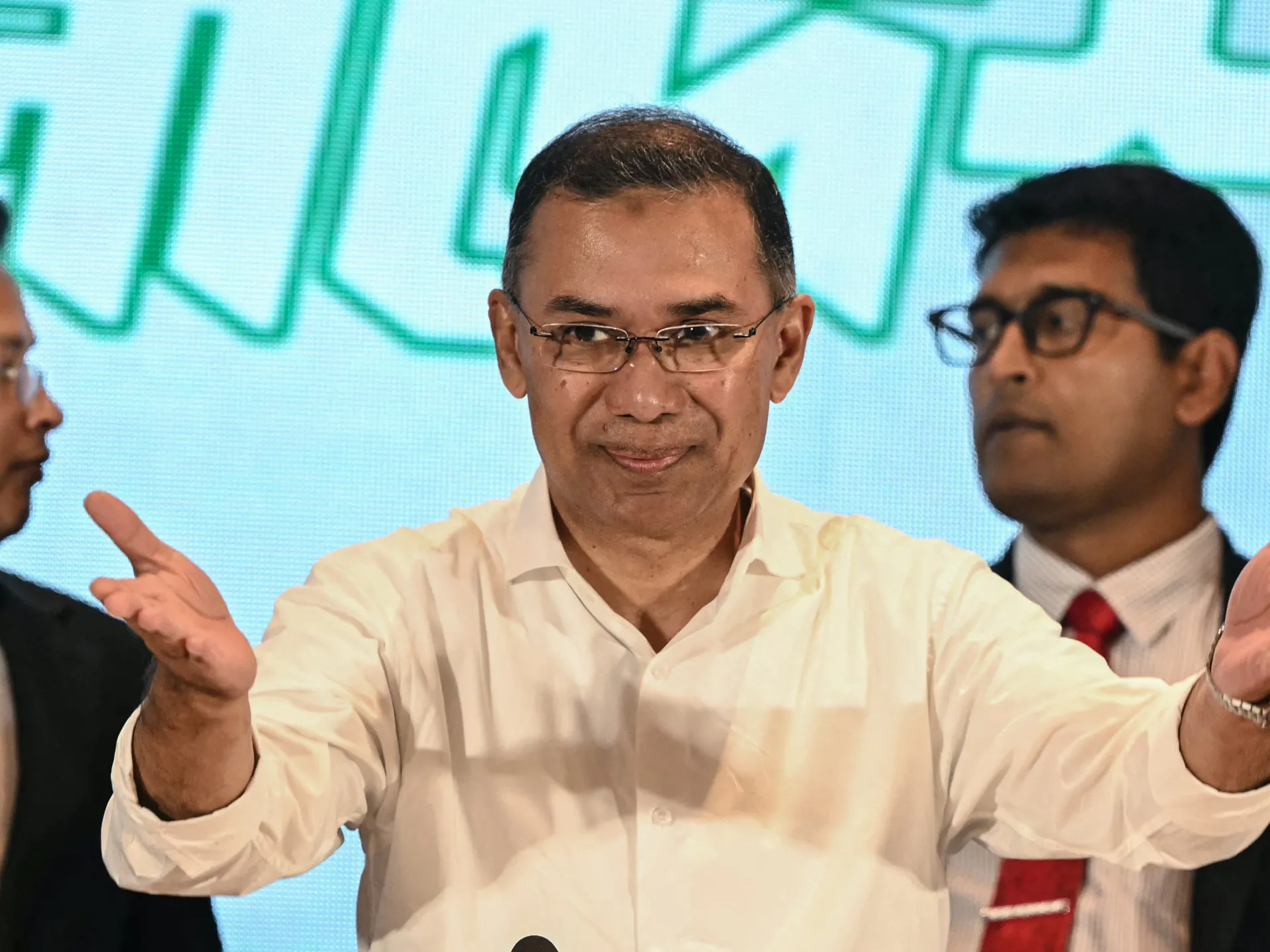

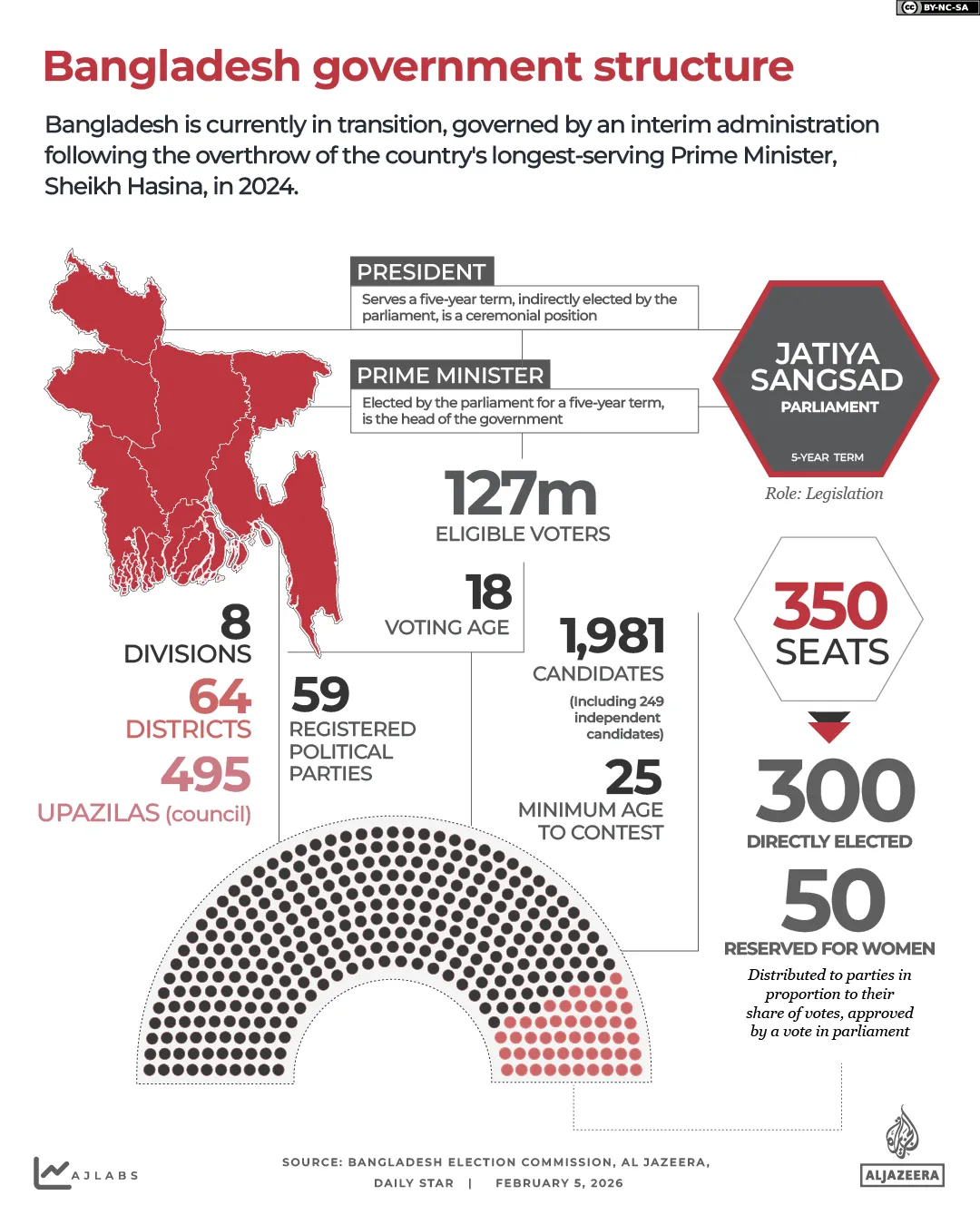

Tarique Rahman, leader of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), which swept to a landslide victory in last week’s parliamentary elections, has been sworn in as the country’s first elected prime minister since deadly protests in 2024, which resulted in the ouster of the previous government and its prime minister, Sheikh Hasina.

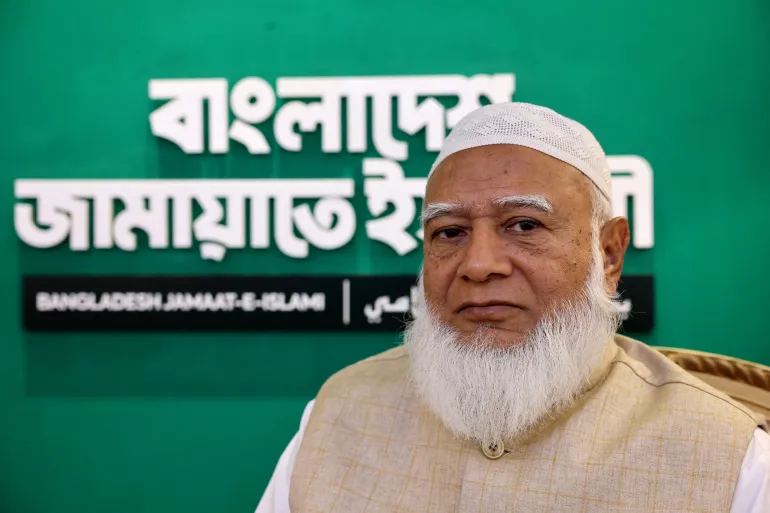

The political alliance led by Rahman’s party won 212 seats in the Jatiya Sangsad, Bangladesh’s parliament, in Thursday’s elections, leaving its main competitor, the alliance led by Jamaat-e-Islami, with 77.

On Tuesday, Rahman took his oath of office, and newly elected MPs pledged loyalty to their country inside the oath room of the parliament building as they were sworn in by Chief Election Commissioner AMM Nasir Uddin.

Foreign officials, among them Pakistan’s foreign minister and the speaker of India’s Parliament, were also present.

Here is what we know about the people who will be running Bangladesh’s new government:

Who are the new cabinet members?

Twenty-five full ministers in the new cabinet took their oaths during a separate ceremony in Dhaka on Tuesday afternoon. The 25 have been drawn overwhelmingly from the BNP and its close allies.

Among the state (junior) ministers appointed to Rahman’s government are Nurul Haque and Zonayed Saki, first-time parliamentarians, who were prominent voices during the 2024 protests.

While members of the cabinet have been announced, the ministries they will be responsible for have not yet been confirmed. Here’s a look at who some of them are.

Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir

Alamgir, who has served as secretary-general of the BNP since 2016, was elected to his seat in parliament by the constituency of Thakurgaon-1, a district in northwestern Bangladesh.

Alamgir, 78, served as a member of parliament from 2001 to 2006 under the previous BNP government, led by Rahman’s late mother, Khaleda Zia, during which he was also state minister for agriculture and later for civil aviation and tourism.

After the end of that government’s term, a caretaker administration took over until elections in 2008, which Alamgir stood in but did not win. He remained a senior member of the BNP outside parliament.

In October 2023, Alamgir was detained by police the day after mass antigovernment protests swept through Dhaka when Hasina’s Awami League party was in power. The police said he had been detained for questioning in connection with the violence that erupted during those demonstrations.

When the BNP win was announced last week, Alamgir hailed the victory and called the BNP “a party of the people”.

Amir Khasru Mahmud Chowdhury

Chowdhury was elected from the Chattogram-11 constituency, which covers the Bandar and Patenga areas of Chattogram city in southeastern Bangladesh.

From 2001 to 2004, Chowdhury served as minister of commerce under the previous BNP administration. He is a member of the BNP’s standing committee.

Before last week’s vote, Chowdhury said that if elected, the BNP would govern by investing in people, “in health, in education and upskilling” and by supporting “artisans, the weavers” and small industries with credit as well as helping them access international markets, including by helping them with their branding.

Iqbal Hasan Mahmud Tuku

Tuku, 75, has been elected as a member of parliament for the Sirajganj-2 constituency in North Bengal.

Tuku is a member of the BNP Standing Committee, the party’s top policymaking body.

He is a veteran BNP figure who has been elected to parliament multiple times and has held important party roles. From 2001 to 2006, he served as the state minister for power. In 2006, he also briefly served as the state minister for agriculture.

In 2007, during the military-backed interim government, a special anticorruption court in Dhaka sentenced Tuku to nine years in prison in a case filed against him by the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC). The ACC accused Tuku of concealing information about assets worth 49.6 million takas (roughly $400,000).

The High Court upheld his conviction and jail sentence in 2023 after a lengthy appeal process. However, in September 2025, a year after the overthrow of the Awami League government, the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court acquitted Tuku.

Khalilur Rahman

Khalilur Rahman is a technocratic minister, appointed for his expertise rather than as a party politician. He is not a member of parliament.

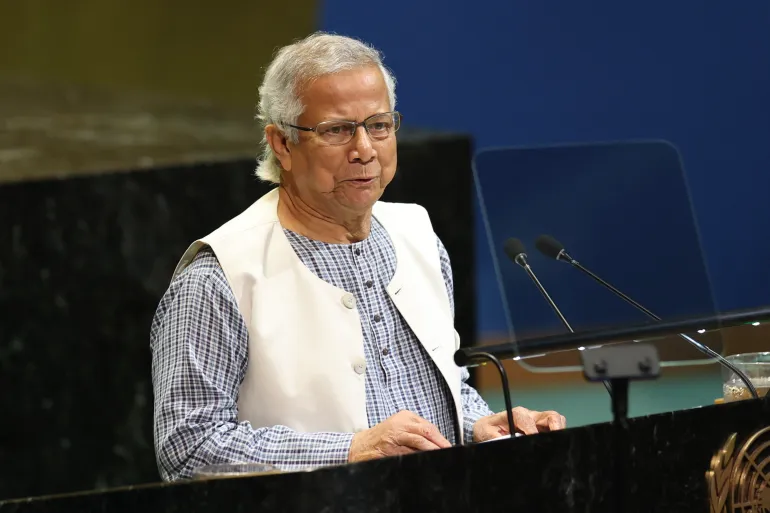

He served as national security adviser in the interim administration headed by Muhammad Yunus, which took over to oversee a transition after Hasina’s ouster.

He also served as the government’s representative for the Rohingya issue during Yunus’s tenure. The refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar in southern Bangladesh are sheltering more than one million Rohingya refugees, most of whom fled Myanmar in 2017 to escape a military crackdown.

Afroza Khanam Rita

The only woman cabinet minister, Rita is a first-time member of parliament but comes from a political family: Her late father was a four-times MP. Rita is also the chairwoman of the Monno Group of Industries, a conglomerate whose firms produce ceramic ware, textiles and agricultural machinery – primarily for export.

Asaduzzaman

Asaduzzaman, was elected from the Jhenaidah-1 (Shailkupa) constituency, which covers Shailkupa upazila in Jhenaidah district in southwestern Bangladesh.

Dipen Dewan

Dewan, 62, a Chakma Buddhist leader, is expected to be named minister of Chittagong Hill Tracts affairs. Dewan won from the Rangamati constituency.

Chakma Buddhists are an ethnic group of Tibeto-Burman speaking people. They are indigenous to the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh and parts of northeastern India.

Nitai Roy Chowdhury

Chowdhury, a Hindu leader, is widely expected to become the minister of cultural affairs.

Chowdhury, 77, has served as a senior adviser and strategist for the BNP’s top leaders.

How significant are these appointments?

During campaigning, the BNP pledged to meet the people’s demand for an elected government with real legitimacy. Therefore, ministers and cabinet members can expect a significant amount of scrutiny, experts said.

Khandakar Tahmid Rejwan, lecturer in global studies and governance at the Independent University, Bangladesh, told Al Jazeera: “The appointees in their respective fields will also face an invisible yet significant pressure to prove themselves more effective and distinctive than the previous administrations, both the interim government and, of course, the Awami League-led government under Sheikh Hasina.”

He added: “It will be particularly interesting to observe whether, after a youth-led mass uprising, the core of executive power is taken over by the old guard or by new faces that reflect diversity in terms of age, gender, ethnicity and religion.”

While two prominent figures from the 2024 student uprisings have been named as state ministers – Nurul Haque and Zonayed Saki – Rejwan added that leaders of the student-led National Citizen Party, which was founded after the 2024 uprising, had made a “strategic mistake” by allying with Jamaat instead of the BNP.

“They had the option to form an alliance with the BNP, which they later abandoned in favour of Jamaat. Given these political dynamics, it is unlikely that any student leaders will receive cabinet positions.”

Who attended the ceremony to swear in the new cabinet?

Several foreign delegations were in Bangladesh to attend the ceremony.

They included Maldivian President Mohamed Muizzu and Bhutanese Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay.

India was represented by Om Birla, the speaker of its lower house in Parliament. Pakistani Federal Minister for Planning Ahsan Iqbal also attended.

Leaders and representatives from Nepal and the United Kingdom, China, Saudi Arabia, Turkiye, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Brunei were among those who were invited to attend.