With Winter Olympics over, L.A. is officially on the clock for 2028 Summer Games

VERONA, Italy — In fair Verona, L.A., unofficially, takes the torch.

While the Olympic flag passed from Italy to France at Sunday’s closing ceremony, handing off the Winter Games from Milan-Cortina to the French Alps, the flame will burn next in L.A.

In just over two years, the United States will host the country’s first Summer Games since 1996, welcoming an Olympic movement that is surging in popularity but unsteady in a changing world, as the Games return to Los Angeles for the third time.

The Milan-Cortina Olympics are expected to rake in record TV numbers for NBC. They already produced the most-watched women’s hockey game on record when an average of 5.3 million viewers took in the United States’ thrilling overtime win over Canada. The rivalry game contributed to the largest weekday audience for a Winter Games since 2014 with an average of 26.7 million viewers who also watched U.S. star Alysa Liu win the country’s first Olympic gold medal for women’s singles figure skating in 24 years.

The smiling 20-year-old with horizontal stripes in her hair became a sensation in Milan just as 41-year-old mother of two Elana Meyers Taylor did in Cortina d’Ampezzo after the five-time Olympian won her first gold medal in bobsled, jumping into the arms of her nanny and, through tears, signing to her deaf children, “Mommy won.”

No matter protests, politics or planning hurdles, the Olympics sought to remain a stage for those athletes to shine.

“You showed us what excellence, respect and friendship look like in a world that sometimes forgets these values,” International Olympic Committee President Kirsty Coventry said to the Olympians in her speech while standing on a platform in the stands placed in front of the Italian delegation. “You showed us that the Olympic Games are a place for everyone. A place where sport brings us together.”

After record numbers from the 2024 Paris Summer Games, the Milan-Cortina Games sold 1.3 million tickets, which, accounting for 80% of the expected tickets, was “beyond our expectations,” Milano Cortina 2026 chief executive officer Andrea Varnier said at a news conference. Of the 63% of international fans who attended the Games, the United States, at 14%, bought the second-most tickets.

Fans filled arenas that were finished just in time in Milan. They withstood snowstorms in Livigno, cheered the debut of ski mountaineering in Bormio and held their breath while multiple skiers got airlifted off the downhill course in Cortina.

The most widespread Games in history created distinct pockets of Olympic spirit separated by hours on trains and miles of winding mountain roads. The Olympics that preached harmony finally united in a single city known for love, beauty and grudges. The Milan-Cortina Games represented seemingly every Shakespearean theme.

Athletes got engaged. Sponsors organized hair and makeup sessions in the Olympic villages, which went through an average of 365 kilograms of pasta and 10,000 eggs a day. A cheating scandal rocked curling.

The closing ceremony set at the Roman amphitheater at the heart of the city that inspired “Romeo and Juliet” celebrated the Games as “beauty in action.” But beneath the glittering gold medals, there was pain.

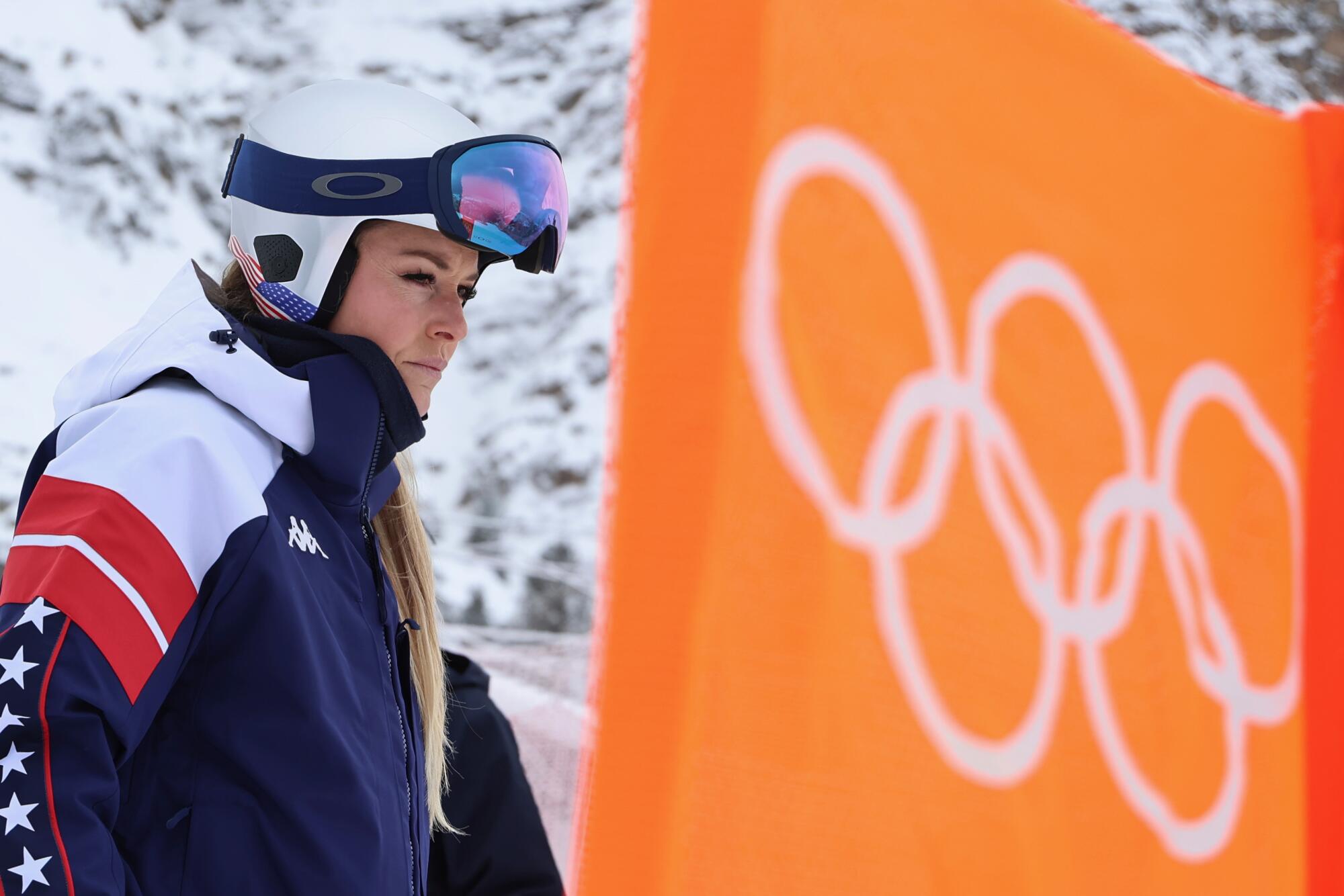

Alpine skier Lindsey Vonn suffered a horrific crash and has already undergone four surgeries on her broken leg. Ukrainian skeleton athlete Vladyslav Heraskevych was disqualified when he refused to compete without his helmet honoring Ukrainian athletes who’ve been killed in the war with Russia.

Artists perform during the closing ceremony of the 2026 Winter Olympics in Verona, Italy.

(Bernat Armangue / Associated Press)

Already holding the weight of their personal dreams, U.S. athletes faced additional pressure answering questions about the country’s political landscape. After freestyle skier Hunter Hess he said he had “mixed emotions” representing the United States at the Olympics, President Trump called the 27-year-old “a real loser” on social media.

Two weeks later, Hess held his thumb and forefinger in the shape of an “L” to his forehead after his first qualifying run.

Athletes pleaded for assistance navigating an onslaught of social media threats as the Olympic spotlight grows with every Games. Coventry said at a news conference last week that the IOC has a safeguarding unit that monitors the organization’s social media platforms for hateful messages. More than 10,000 such comments were taken down during the Paris Games, IOC spokesperson Mark Adams said. The number for the Milan-Cortina Games hadn’t been finalized.

With the largest delegation of any country at the Games, the United States won the second-most medals with 33, including 12 golds, the most Olympic titles for the country at any single Winter Games. The total gold medals surpassed the 10 won in Salt Lake City in 2002, the last time the United States hosted an Olympic Games.

After more than two decades away, the Games will return to the United States twice in the next eight years. L.A. will host the 2028 Games and Utah will have the 2034 Winter Games.

Approaching the final stretch of an 11-year planning period, the L.A. Games confronted another challenge this month when a growing number of local politicians called for LA28 chairman Casey Wasserman’s resignation after racy emails he exchanged with Ghislaine Maxwell were revealed in the Epstein files. After initial hesitation, L.A. Mayor Karen Bass and other leaders joined the chorus calling for Wasserman’s dismissal.

But LA28 doubled down on his role. The executive committee of the LA28 board stood by Wasserman after a review from an outside legal firm found that the Hollywood mogul’s relationship with Maxwell “did not go beyond what has already been publicly documented.”

As with his 2026 organizing committee counterpart Giovanni Malago, Wasserman would be expected to deliver speeches in 2028.