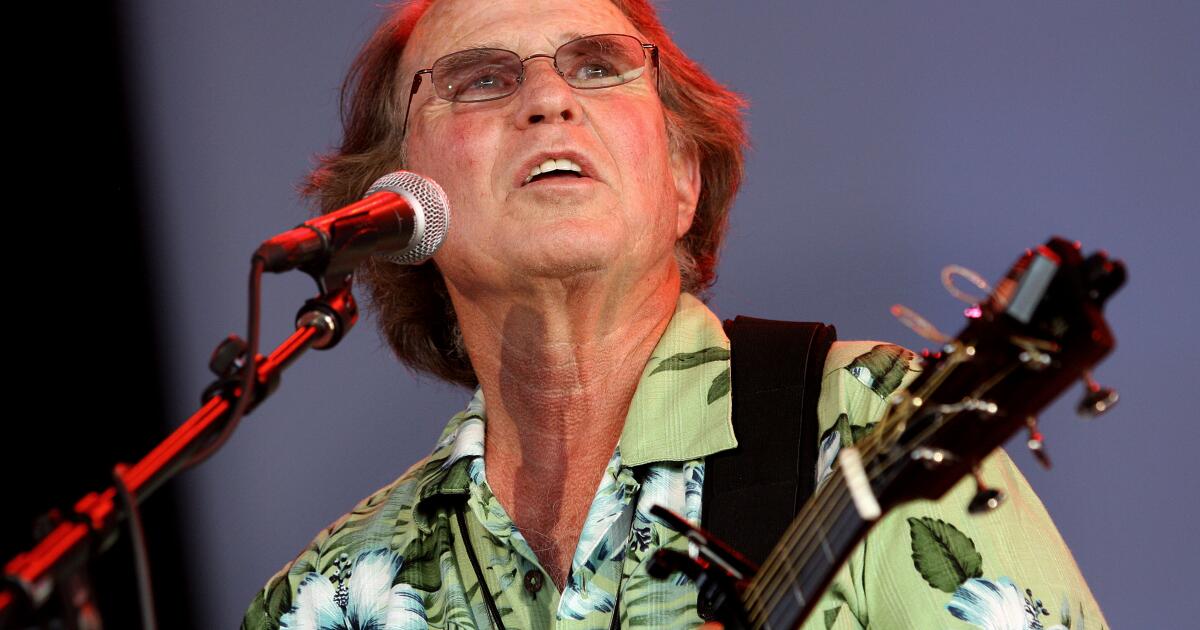

Joe McDonald, Woodstock legend and anti-war activist, dead at 84

Joe McDonald, lead singer and songwriter of Country Joe and the Fish — the band known for its resounding anti-war chant at Woodstock — has died. He was 84.

His wife, Kathy McDonald, announced his death Sunday morning. He died Saturday in his Berkeley home due to complications from Parkinson’s disease.

As a formative member of the American counterculture in the 1960s and ‘70s, McDonald leaves a legacy of bridging contemporary political satire and brazen anti-war sentiments with the early sounds of acid rock.

“We’re just so proud of him. He’s our hero. He instilled in us that we have to speak up when we can, on whatever platform we can, about issues that we feel are important,” said his daughter Seven McDonald, a film producer, music manager and writer.

“While he was a very serious, earnest activist, he also had such an acute sense of cynical humor that is so fantastic and was capable of scathing satire,” her brother Devin added. “He’s most famous for that, but he also did so many heartfelt benefits for different causes.”

The siblings, who spent their childhoods on the road and in recording studios with him, joke that he was always doing a benefit show.

The musician was born on Jan. 1, 1942, in Washington to Worden McDonald and activist Florence (Plotnik) McDonald, who were both members of the Communist Party. The family soon moved to the Southern California city of El Monte, where Joe McDonald was raised.

His musical roots reach back to when his father taught him to play the guitar at 7 years old. But before embarking on his career in music, McDonald enlisted in the Navy at age 17. He served as an air traffic controller at the Atsugi, Japan, air facility for three years. Upon coming back to the states, he tried out college for a short time before dropping out and moving to Berkeley.

Before experimenting with an early variation of Country Joe and the Fish alongside guitarist Barry Melton in the mid-1960s, McDonald started a small magazine called Rag Baby. Once the group was solidified, they decided to turn their folksy roots electric and made the move to San Francisco — just before the city’s legendary Summer of Love.

The group, born out of the Bay Area psychedelic rock scene, was soon signed by Vanguard Records and in 1967 released its debut album “Electric Music for the Mind and Body.” At the time the band’s label and producer were hesitant to let the musicians fully express their politics, and excluded the soon-to-be-hit anti-war anthem “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag” with the catchy chorus that began, “And it’s 1, 2, 3 what are we fighting for?”

Instead, they went with tracks like “Superbird,” a spoof of President Lyndon B. Johnson, which received little to no backlash. When the second album came around, the band was allowed to run with “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag” as the title track. Trouble started to arise with the anti-Vietnam war anthem when the group changed the beginning chant of F-I-S-H to a more profane four letter word that starts with an “F.”

They performed this altered cheer at a gig in Massachusetts, where McDonald received a charge for inciting an audience to lewd behavior and a $500 fine. With this police run-in, Country Joe and the Fish received a slew of press, riling up the public ahead of their Woodstock performance.

The moment the band members began this chant at Woodstock became arguably the biggest moment of their careers, with over 400,000 people joining in. It’s a moment of protest that has gone down in history.

Not long after the festival, the band went their separate ways. McDonald continued to release solo music that stuck with the similar themes of politics and the Vietnam War.

“He took the toll for taking the stand,” said Seven. “He was not the biggest pop star, because he just opted to speak his mind and do his thing.”

In 1986, McDonald released “Vietnam Experience,” an album full of songs analyzing its long-term impacts on his generation. And in 1995 he was “the driving force” according to an Associated Press story, behind a war memorial to honor Berkeley veterans killed in the Vietnam War.

He told The Times in 1986 that he had “an addiction to Vietnam … I’ve been doing work with veterans now for 15 years, and I probably know more about Vietnam veterans than any other person in the entertainment industry.”

“I’ve always believed that the veterans are a basic element to the understanding of war,” he added, “and the understanding of war is the only path to peace.”

McDonald is survived by his wife of 43 years, Kathy; his five children, Seven, Devin, Ryan, Tara Taylor and Emily; a brother, Billy; and four grandchildren.