Inside Wallis Annenberg’s final days: Opioids, police visit and a bitter family feud

In the final weeks of philanthropist Wallis Annenberg’s life, her family and closest friends were consumed by a fierce power struggle over her medical care, court records show.

Three of her children — Gregory, Lauren and Charles — believed their mother was being mistreated during her most vulnerable time, wrongfully confined to her bed, isolated from family and longtime staff and overmedicated to the point of stupor.

They blamed their mother’s longtime partner, Kris Levine, and Kris’ older sister, Vikki Levine.

Vikki, who served as Annenberg’s personal assistant and held authority over her medical decisions, was exerting control over their mother in “likely fatal” ways, hastening her decline with excess narcotics, the children alleged in court documents. The children said they were shielded from information about their mother and were distressed that the Levine sisters had indicated plans to remove Annenberg’s body from her Century City villa within hours of her death and send her remains for composting before a proper goodbye.

“If there is anything suspicious about her death — which is appearing more and more likely given Vikki’s ongoing abuse of Wallis — it will render it impossible to conduct an autopsy,” the children’s legal team asserted in court filings.

The dispute drew in some of the city’s top lawyers, triggered calls to police and led the Annenberg children to march into Los Angeles County Superior Court in a frantic effort to dislodge Vikki Levine from overseeing their mother’s medical care.

Vikki and Kris Levine adamantly denied over-medicating or mistreating Annenberg, the heiress to her father’s publishing empire who, through her family’s foundation, gave about $1.5 billion to scores of organizations and nonprofits across Los Angeles County.

In court filings, Vikki Levine said the children’s “vicious and false accusations” stemmed from sadness that their mother didn’t disclose to them that her cancer had returned, that they weren’t in charge of her care, that her death was rapidly approaching and that she wanted to die “as gently as possible.”

“The Children have misdirected their pain, grief and anger at the wrong person, which is so much easier than confronting reality,” Vikki Levine said in a court filing in which she also accused the Annenberg children of creating a “toxic environment” when they visited.

Kris Levine, who started dating the heiress in 2009 and had lived with her since 2012, submitted a declaration stating that the Annenberg children had engaged in a campaign of “lies” to their mother, including telling her that her partner was trying to kill her. She insisted that the children had been permitted to visit but lamented that her home had become engulfed by acrimony.

“No one is attempting to hurt Wallis — we love her. No one is keeping her children from her. Despite the outrageous behavior they exhibit in my home at such a sensitive time, they are still welcome,” Kris Levine said in a declaration.

Annenberg had opted to go into hospice in the final weeks of her life, and Kris Levine questioned why the children would defy their mother’s wishes and disparage her choices, particularly in such a public way.

“Nobody controlled Wallis Annenberg and for anyone to say otherwise would contradict the truth and be disrespectful of her and her legacy as one of the most transformative philanthropists of our time,” said Stuart Liner, an attorney for Kris Levine, in a statement to The Times.

This account of the Annenberg family’s internal conflict is based on court records that provide a window into one of Southern California’s most prominent families. Wallis Annenberg’s estate lawyer, Andrew Katzenstein, and the children’s lawyer, Jessica Babrick, declined comment. Representatives for Vikki Levine did not respond to messages seeking comment.

Wallis Annenberg, center, sits between her son Charles Annenberg Weingarten and Kris Levine at a 2015 event.

(Chris Weeks / Getty Images)

Annenberg died Monday at age 86, drawing tributes from former President Biden, Gov. Gavin Newsom, and luminaries in the worlds of art, business and philanthropy.

The public mourning has highlighted Annenberg’s generosity toward elder care, animal welfare and USC, where she was a life trustee, among other causes. The turmoil among those closest to her, however, has persisted following the intense legal battle over her final days.

The dispute, at least so far, has not touched on the Annenberg family’s wealth — or what either side stood to financially gain or lose with the matriarch’s death. It originated, in part, in an advance healthcare directive that Annenberg allegedly signed on July 11, 2023, the year after she was diagnosed with lung cancer, according to court records.

The directive, which was notarized and executed with assistance from Annenberg’s attorney, Katzenstein, endowed Vikki Levine with primary authority over medical decisions and designated Annenberg’s son Gregory Weingarten as an alternate.

Annenberg’s children have since cast doubt on the document, asserting in a court filing that the signature appears to be right-handed, while Annenberg was left-handed.

Vikki Levine, with David Dreier, attends The Wallis Delivers: A Benefit Evening To Support Wildfire Recovery at Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts on April 30 in Beverly Hills.

(Rodin Eckenroth / Getty Images)

Why Annenberg installed Vikki Levine in the role is unclear. In court papers, she is described as Annenberg’s best friend, personal assistant and sister to “life partner” Kris Levine. Voting records show that all three women resided at Annenberg’s home. Vikki Levine had worked for the heiress since at least the mid-2000s, when Annenberg installed her as trustee over a granddaughter’s trusts, court records show.

Although Kris Levine was not listed among Annenberg’s survivors in several obituaries, she was a mainstay in her life, publicly accompanying her to events and co-chairing philanthropic events.

Last fall, after being in remission, Annenberg’s cancer returned. According to a court filing by Vikki Levine, the philanthropist decided not to tell her children or anyone but her “closest friends.”

“Wallis determined not to seek treatment, but to enjoy as much as possible, the time she had left,” according to the filing.

In April, after Vikki Levine told Annenberg’s children about their mother’s health, they “had nearly unlimited access to Wallis,” the filing said, asserting that the children’s claims rest on scores of in-person interactions with her, making it unlikely that she was forcibly isolated.

“Wallis has been visited virtually daily by her Children and/or grandchildren, and has 24 hour care by experienced medical staff,” Vikki Levine’s attorneys said.

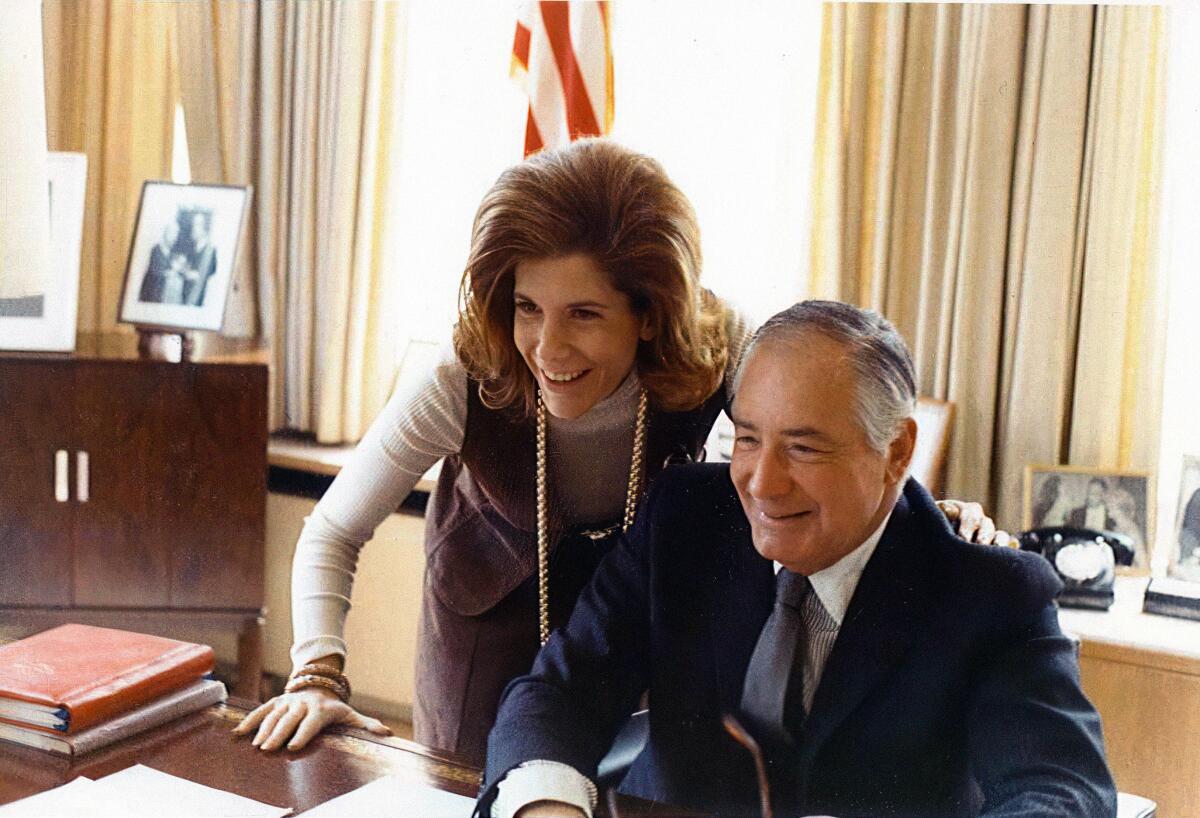

Wallis Annenberg, seated, with her children Gregory Annenberg Weingarten, Lauren Bon and Charles Annenberg Weingarten.

(Hamish Robertson)

Around early May, Annenberg began hospice, with medication aimed to alleviate pain and anxiety from her decreased lung function, according to a declaration from one of her hospice nurses that was reviewed by The Times.

But the Annenberg children were growing increasingly alarmed, they said in court filings.

In June and early July, Vikki Levine had dismissed longtime household staff and was demanding that a new team overmedicate their mother, “administering excessive amounts of powerful narcotics and opioids, such as Fentanyl, Morphine, Ativan and other similar drugs,” the children alleged in a court filing.

The cocktail of narcotics kept their mother “in a vegetative state” and risked catastrophe, the children claimed, writing, “When Wallis is able to emerge from this near-comatose state, she is adamant that this is not what she wants and that she believes, in her own words, that Vikki is ‘kidnapping her.’”

To back their accusations, the children provided a judge with signed declarations from three of their mother’s caregivers, who said they had been ousted around late June after observing shocking scenes, including forgery of records and misrepresentations to Annenberg’s doctors.

“I witnessed Vikki forcing pills in Ms. Annenberg’s mouth when she clearly did not want to take them. I told Vikki that Ms. Annenberg seemed calm and did not need more medication,” said Annenberg’s housekeeper and caregiver of nearly 20 years. “Vikki told me the pills were for her upset stomach, but I told her that I knew they were Ativan because I saw the bottle.”

Another healthcare worker — a registered nurse of 40 years employed by a concierge medical service — said she was dismissed shortly after she objected to providing Ativan to Annenberg, who at the time was sleeping and did not appear anxious or agitated.

The nurse alleged that Vikki Levine forbade the staff from keeping a proper medication log and allowed Annenberg to drink alcohol, even while on medication.

“It is difficult for me to believe that this kind of conduct can happen to anyone, let alone Ms. Annenberg. No one deserves to be rushed to death,” the nurse said in her sworn declaration.

Lawyers for Vikki Levine said that all three former staffers supporting the Annenberg children had been fired “for cause,” but did not elaborate.

Before turning to the courts, the children asked Dr. Peter Phung, of Keck Medicine of USC, to visit their mother. Phung “determined that she was, indeed, being overmedicated” and trimmed her dosage, the children claimed in court filings.

“As a result, Wallis had her best day in weeks,” the children said. “Unfortunately,” they continued, Vikki Levine blocked access to the doctor, and she and her sister “completely barred” the children’s visits on July 13.

The following morning, the children petitioned a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge to suspend Vikki Levine’s authority as Annenberg’s healthcare agent and appoint one of her sons or a third-party professional instead. The children also asked the judge to impose a three-day period before Annenberg’s body could be transported out of L.A. or cremated.

In a 73-page filing, the children provided extraordinary details about their mother’s medical care, along with their concerns, situating their petition as an act of desperation.

“We have been informed that my mother may only have weeks to live, and I do not want those weeks to be spent in a medically-induced coma due to Vikki’s actions, which are contrary to medical advice and harmful to her well-being,” daughter Lauren Bon said in a declaration.

Annenberg’s daughter, artist Lauren Bon, stands in an L.A. River project site in 2023.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times)

Vikki Levine and her sister vehemently contested the allegations, denying any abuse and claiming that the children were misinformed or omitted key information.

“Dr. Phung did not determine that Wallis was being over-medicated as alleged,” said one of Vikki Levine’s filings. “To the contrary, Dr. Phung confirmed to Vikki that there has been ‘no mismanagement of symptoms.’”

Annenberg, they said, was confined to the bed because of doctor’s orders, not cruelty.

A hospice nurse who saw Annenberg nearly daily in the final weeks of her life also contested many of the claims of the children and the former caregivers.

The nurse, according to a signed declaration reviewed by The Times, said Annenberg’s care relied on direct orders from her physicians and was carried out by registered nurses from VITAS, a hospice service. The medical team kept all appropriate records, and Annenberg was confined to her bed because moving would have risked dangerous falls, respiratory distress and other calamities.

The Levine sisters portrayed the Annenberg children as improperly interfering in their mother’s affairs.

“They crowd around Wallis’ bed while the nurses are caring for her, tell Wallis that she doesn’t need the medication, refuse to get out of their way, ask numerous questions about the medication and procedures being employed, and generally make the situation untenable for a care-provider to work,” Kris Levine said in a declaration submitted to the judge.

While Kris Levine acknowledged that she had halted visits from the children on July 13, she said in a court declaration that she asked them not to come that day because of a series of heated confrontations, and that she had wanted to impose visiting hours to give Annenberg some rest and continuity.

“The children, particularly Gregory Weingarten, have aggressively refused my requests. Indeed, he has insisted that my name is ‘not on the deed,’ that I have ‘no rights’ to our home, and that he had ‘more rights’ to be there than I did,” Kris Levine said in her declaration.

The tensions boiled over with “multiple” calls to police by Annenberg’s children.

Vikki Levine said that when officers arrived on a recent Friday night, they “determined that there was no mistreatment of Wallis, no elder abuse as alleged, and told Vikki that she did not need to let the Children back into the house.”

Nevertheless, both Vikki and Kris Levine said they made it clear to the children that they could still visit their mother.

On July 22, Judge Gus T. May found that there was “good cause” to suspend Vikki Levine from serving as Annenberg’s healthcare agent.

In her place, the judge appointed Jodi Pais Montgomery, a professional fiduciary who has held roles in other celebrity cases in probate court, including Britney Spears and Carol Burnett’s grandson.

Montgomery was instructed to follow Annenberg’s advance healthcare directive and share confidential medical information with the Annenberg children, as well as with the Levine sisters.

Annenberg died less than a week later.