Percussionist Walfredo de los Reyes Sr. dies at 92

The Times spoke with De los Reyes’ son Daniel, who shared his father’s last words to him: “Always play your best.”

Walfredo de los Reyes Sr., the internationally lauded Cuban percussionist who had a prodigious six-decade career in the music industry, died Aug. 28 in Concord, Calif. He was 92.

Walfredo de los Reyes Jr. — who plays drums for the legendary rock band Chicago — shared the news of his father’s death in an Instagram post last week.

“My father, Walfredo de los Reyes Sr., passed away last night, surrounded by his loving wife, Debbie, my brother Danny, and my wife, Kirsten,” he wrote. “He was not only an incredible father, but also a mentor in music and in life. He will always live in my heart. … His spirit, his rhythm will never stop.”

Speaking with The Times, De los Reyes’ son Daniel, drummer of the Grammy-winning country group Zac Brown Band, recalled his most recent memories of his father and the pain of his loss.

“I did everything I could to help him in his last months, his last days, as far as comfort,” he said. “You see a bunch of testimonials that everybody’s been writing in… but to me, he’s just my father. He’s just my father that I help out and I go to work with. To process everything [has] been very, very difficult. He was my Superman. He was like my Bionic Man. I thought, ‘Nothing’s ever going to happen to him.’ And the end has finally come.”

Walfredo de los Reyes Sr. plays congas onstage.

(Courtesy of Daniel de los Reyes)

While he hopes that his father’s musical legacy is preserved and appreciated, Daniel also wants people to remember the person his father was outside the industry.

“He would take in whoever it was and help them,” Daniel said. “[It] didn’t matter where they were from. If they called him, I can assure you, he would invite him to the house he would share with them — make them feel like they were part of his family immediately.”

Daniel also shared his father’s last words to him: “Always play your best.”

“It wasn’t just playing in the music instrument,” he said. “It was being the best person that you could possibly be. And that when you close your eyes at night, you feel good with yourself.

“I’m going to take those last words and that’s going to be my mantra for the rest of my life. I always try to be the best person as possible, but now it’s just I have my father’s love shining through me.”

Walfredo de los Reyes III was born in Havana on June 16, 1933, into a musical family. His father, Walfredo de los Reyes II, was a trumpeter who helped found the Orquesta Casino de la Playa in 1937.

De los Reyes would go on to play percussions alongside Latin music icons like Tito Puente, Cachao López, Willie Bobo and Cuban singer La Lupe. He also performed with famous American acts such as Tony Bennett, Sammy Davis Jr., Linda Ronstadt, Dionne Warwick, Steve Winwood and Debbie Reynolds. He expanded his list of featured performances through his longtime residence in Las Vegas where he shared the stage with Milton Berle, Wayne Newton, Robert Goulet, Bernadette Peters and Rita Moreno.

His signature style of simultaneously playing a drum kit and percussion instruments was inspired by both Cuban and American influences — like Candido Segarra and Ed Shaughnessy — but also by necessity.

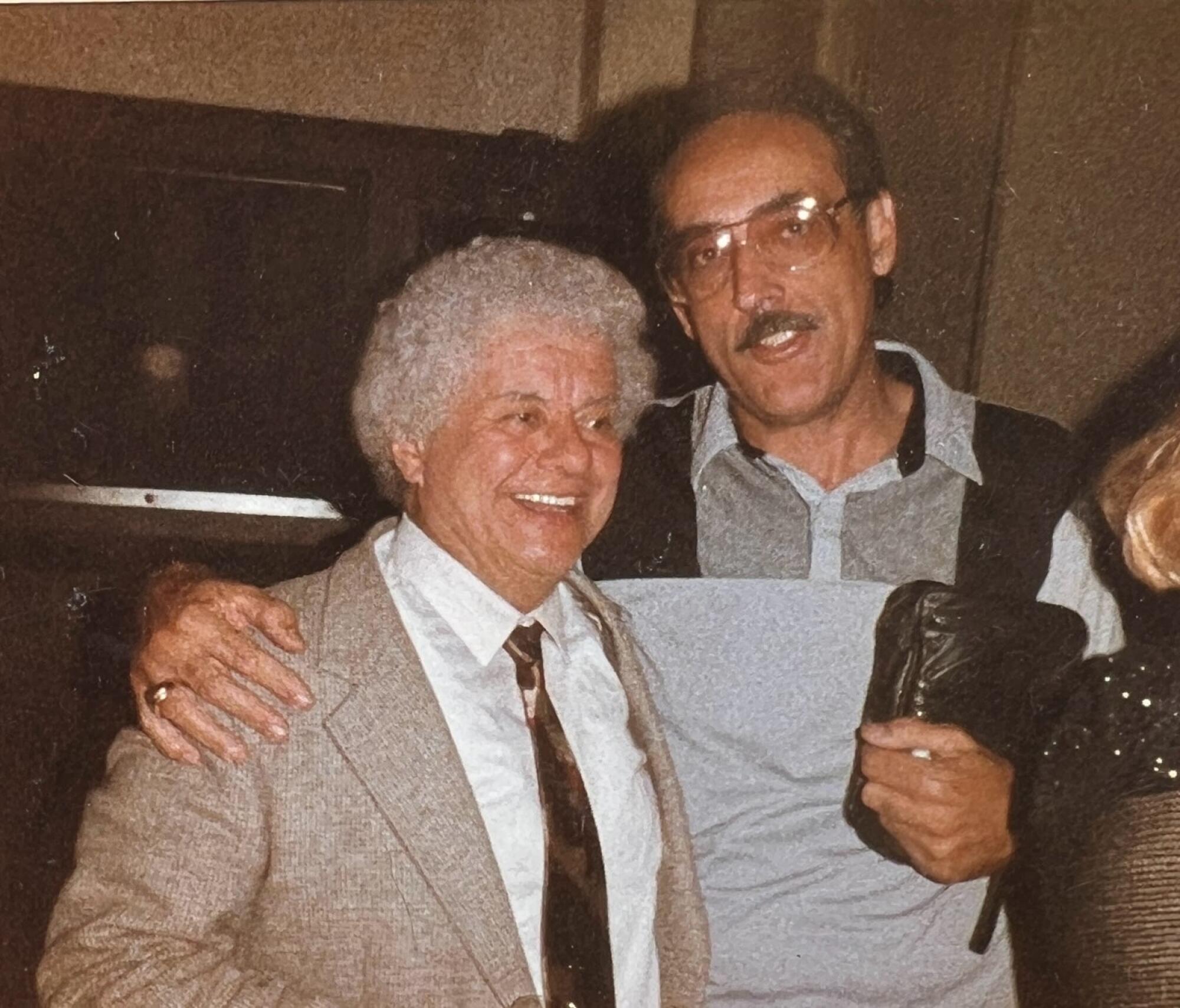

Tito Puente, left, poses for a photo with Walfredo de los Reyes Sr.

(Courtesy of Daniel de los Reyes)

“When I got my band at the Casino Parisien [in Havana], I didn’t have enough [money] to [hire] a conga player,” De los Reyes said in a 2011 interview with the National Assn. of Music Merchants. “I had to decide between a conga and a singer. I got the singer, because you always need a singer. [Then] I started putting congas on the left side [of my drum set] and playing with my left hand, the tumbao. … Why should I play only a conga drum? My feet just lay there.”

Figures from across the music world shared tributes to De los Reyes, including Tito Puente Jr., Gregg Bissonette, Luis Conte, Raul Pineda, Horacio “El Negro” Hernandez, Israel Morales and Al Velasquez.

He is survived by his wife, Debbie Bellamy de los Reyes, his five children and 10 grandchildren. His son, actor Kamar de los Reyes, died of cancer in 2023 at age 56.