Here’s a look at the elusive Birdman mentioned in Monster: The Ed Gein Story

WARNING: This article contains spoilers from Monster: The Ed Gein Story

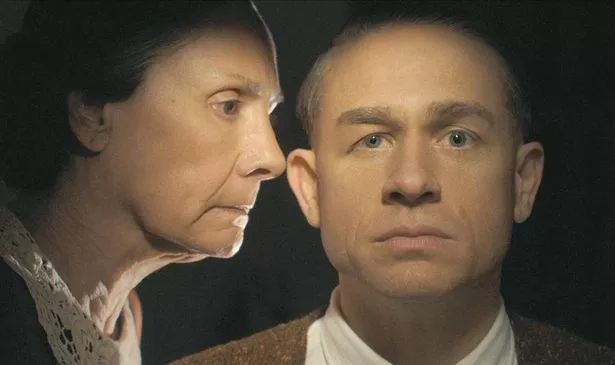

Netflix‘s latest sensation, Monster: The Ed Gein Story, has been gripping viewers worldwide since its release on 3 October, reports the Manchester Evening News.

The series boasts a cast of real-life characters, including Ilse Koch (portrayed by Vicky Krieps), Psycho star Anthony Perkins (played by Joey Pollari), and Adeline Watkins (Suzanna Son), among others.

This third instalment of Ryan Murphy’s true crime anthology series also features notorious serial killers like Ted Bundy (John T. O’Brien) and Richard Speck (Tobias Jelinek).

However, many are curious about the enigmatic Birdman.

Who is the Birdman in Monster: The Ed Gein Story?

The series shows Speck writing letters to Ed Gein (Charlie Hunnam), discussing his prison experiences and citing the Plainville Ghoul as his muse.

Speck also refers to the Birdman, another real-life serial killer, better known as the infamous American criminal Robert Stroud.

READ MORE: Did Ed Gein really kill the nurse in hospital?READ MORE: Did Ed Gein kill Adeline Watkins?

Convicted murderer Stroud killed a bartender and assaulted fellow inmates and guards while in prison. In 1916, he murdered a prison guard and was sentenced to death, but this was commuted to life imprisonment in solitary confinement.

He earned the monikers ‘Birdman’ and ‘Birdman of Alcatraz’ after caring for a nest of three injured sparrows he found in the prison yard during his time at Leavenworth.

After a couple of years, he’d accumulated 300 canaries and would go on to study and pen the book Diseases of Canaries, published in 1933.

He was permitted to continue his pastime because it was deemed a constructive way to spend his time, according to Alcatraz History.

Get Netflix free with Sky

Sky is giving away a free Netflix subscription with its new Sky Stream TV bundles, including the £15 Essential TV plan.

This lets members watch live and on-demand TV content without a satellite dish or aerial and includes hit shows like Stranger Things and The Last of Us.

Stroud carried on studying avian ailments and documenting their behaviour and anatomy, even selling remedies for them.

However, his apparatus and bird studies came to an abrupt halt when it was discovered he’d been using his kit to brew alcohol on the side.

In 1942, Stroud was relocated to Alcatraz, where he would remain for the following 17 years of his existence.

In 1959 Stroud was transferred to the Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Missouri and passed away four years later in 1963 of natural causes.

He was brought to life on the big screen by Burt Lancaster in the film Birdman of Alcatraz, which secured the actor an Oscar nomination for Best Actor.

Fascinatingly, the reason Speck may have also referenced Birdman was due to his own encounters with a sparrow whilst incarcerated.

According to Mindhunter FBI Agent Robert Ressler’s book Whoever Fights Monsters, Speck caught a sparrow and kept it as a companion.

When he was cautioned by a prison officer that he’d be placed in solitary confinement if he didn’t free the creature, Speck murdered the bird by hurling it into an overhead fan.

The shocked guard enquired why Speck had carried out the brutal act, to which the serial killer was reported to have said: “[B]ut if it ain’t mine, it ain’t nobody’s.”

Monster: The Ed Gein Story is streaming on Netflix now