Sweden’s A26 Diesel-Electric Submarine Scores Big Win With Polish Order

Poland’s next submarines will be provided by Sweden, in the shape of the advanced A26 class. Under the long-running Orka acquisition program, Warsaw announced today that it will buy three of the boats, which use an air-independent propulsion system, to replace the Polish Navy’s single Soviet-era Kilo class submarine. The new multirole subs will be able to launch and recover uncrewed underwater vessels (UUVs), as well as be used for minelaying, intelligence collection, anti-surface warfare, anti-submarine warfare, and more.

The Saab design was chosen in favor of competing offers from France’s Naval Group, Germany’s ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems, Italy’s Fincantieri, South Korea’s Hanwha Ocean, and Spain’s Navantia.

“We are honored to have been selected and look forward to the coming negotiations with the Armaments Agency in Poland,” said Micael Johansson, president and CEO of Saab, in a statement announcing the order today.

“The Swedish offer, featuring submarines tailored for the Baltic Sea, is the right choice for the Polish people. It will significantly enhance the operational capability of the Polish Navy and benefit the Polish economy,” Johansson added.

The Swedish offer was made by the country’s government on behalf of Saab. At this point, no contract has been signed, but Saab and the Swedish Defense Materiel Administration (FMV) will now complete the procurement process together with Polish authorities.

Statements on Poland’s selection of the A26 were also provided by the Prime Minister of Sweden, Ulf Kristersson, and Pål Jonson, the Swedish Minister of Defense:

Saab says that the deal will include industrial cooperation with Poland as well as technological transfer, as part of a broader strategic partnership between the two countries. For Sweden, the first export customer for this promising design provides a significant boost to the program, at a time when delays and cost overruns mean it’s much-needed. A total of five boats increases the demand for in-service support, and the Polish seal of approval could open the door to more exports.

Although it has been reported that the three submarines will cost $2.52 billion, it remains unclear when they might be delivered.

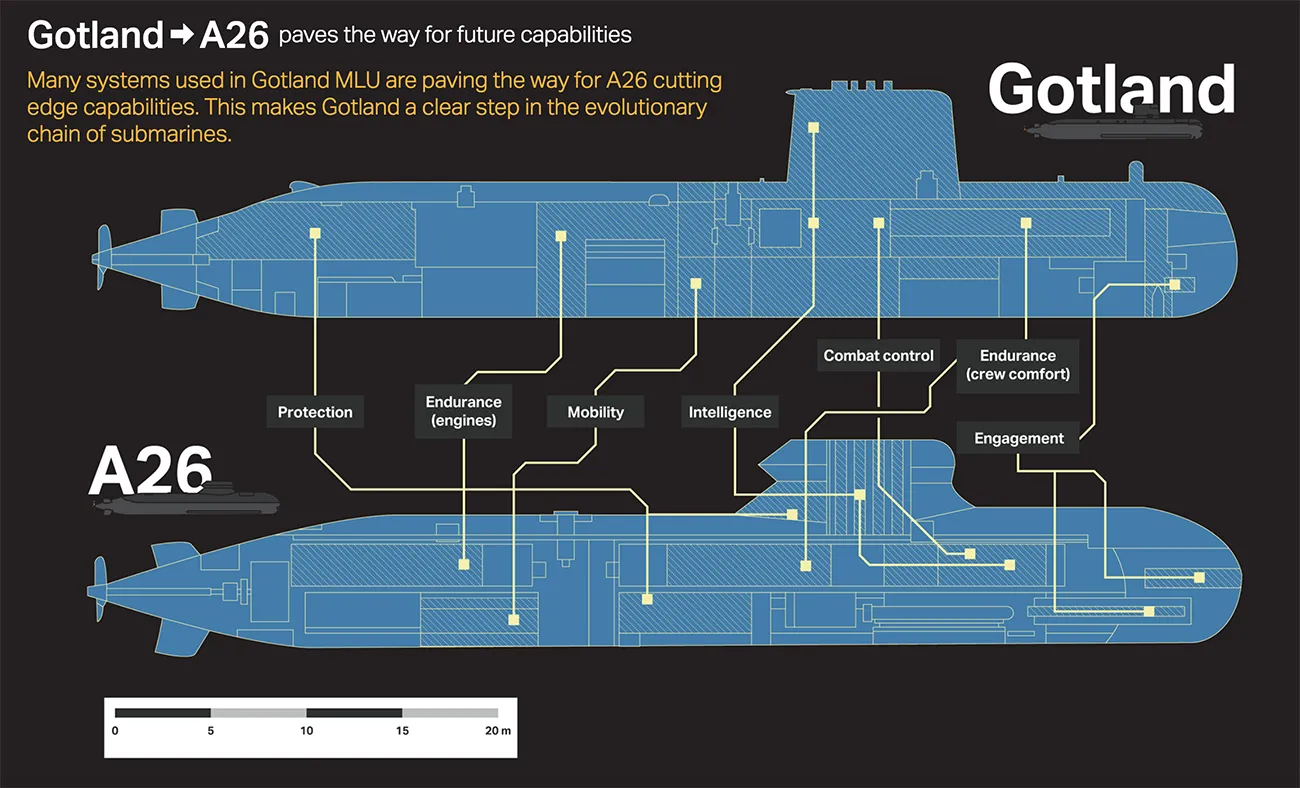

The A26 uses air-independent propulsion (AIP), a technology that The War Zone has examined in detail in the past. Specifically, as well as diesel engines, this employs a Stirling-type engine as previously used in the influential Swedish Gotland class design. The Stirling auxiliary engine burns liquid oxygen and diesel to drive electrical generators that can be used for either propulsion or charging the batteries. The result is a conventionally powered submarine that’s able to remain submerged for reportedly more than 18 days, without needing to surface or use a snorkel.

The A26 has the option of being fitted with vertical launch system (VLS) cells, compatible with Tomahawk land attack missiles, which might be of interest to Poland as it seeks to reinforce its long-range strike capabilities.

Another notable feature of the A26 design is its sail, which is raked along its leading edge and which flares out toward the top. As we have discussed in the past, this feature is understood to have been chosen to increase its stealth characteristics. The A26 also features an X-form rudder. As we have discussed in the past, this configuration provides improved maneuverability, efficiency, and safety, and also helps reduce the acoustic signature across significant parts of the submarine’s operating envelope compared to the more traditional cruciform system.

Other details of the A26 design include a length of around 217 feet and a surfaced displacement of 2,122 tons. The submarine has a standard complement of just 26 sailors but can also accommodate up to 35 more, including commandos for special forces missions. The commandos can be delivered via the Multi-Mission Portal, similar to an oversized torpedo tube, which provides access to a flexible payload lock.

The A26 is also being built for the Royal Swedish Navy, with two Blekinge class boats under construction at Saab’s Kockums shipyard in Karlskrona. Originally planned to be handed over in 2024 and 2025, it recently emerged that delays would push the delivery of the first of these boats to 2031, while increasing costs will see the program reach a price tag of 2.3 billion Euros (around $2.7 billion). The second Swedish submarine is scheduled to be delivered in 2033. Between them, the new boats will replace the Royal Swedish Navy’s two Södermanland class submarines.

Buying three advanced submarines marks a major advance for the Polish Navy, which has, for many years, only had a single Project 877E Kilo class submarine, the ORP Orzel, in its fleet. The age of this boat and the impossibility of obtaining spare parts and support from Russia mean that it’s unclear if the Orzel is currently operational.

As Saab’s Johansson pointed out, the Polish Navy will be getting a submarine that has been purpose-designed for the Baltic Sea. Notably shallow and confined, with dense littorals, including complex undersea obstacles and islands, the Baltic imposes very particular requirements on submarine designs, something that has long been reflected in successive classes built in Sweden (as well as in Germany).

In particular, the Baltic environment calls for diesel-electric submarines that are able to transit covertly in areas with a water depth of less than 82 feet and operate in an environment with a potentially high density of anti-submarine warfare forces and naval mines.

Warsaw’s investment in the three new submarines is just one part of a much larger defense spending spree — what the Polish Armed Forces themselves describe as “one of the highest levels of defense spending in NATO.”

The Polish Air Force is gearing up to receive 32 F-35A fighters, which will be armed with long-range precision weapons. Dozens of FA-50 light combat aircraft are also being delivered.

Within the air defense branch, Poland plans by 2032 to introduce new air and missile defense systems procured under the Narew and Wisła programs, which cover the short-range and medium-range air defense segments, respectively.

Meanwhile, the Polish Land Forces are getting 250 of the latest Abrams M1A2 SEPv3 tanks, worth up to $6 billion, that will serve alongside a similar number of German-made Leopard 2s already in use. The Land Forces also expect to benefit from additional investments in operational fires, including new tube and rocket artillery, which will be employed in combination with 96 new AH-64E Apache attack helicopters. Furthermore, a significant South Korean arms package includes tanks, short-range ballistic missiles, and self-propelled artillery, as well as the aforementioned FA-50s.

Alongside the new submarines, Polish naval capabilities are also being reinforced by new coastal missile units and mine warfare technologies.

All of this military buildup comes in direct response to Russian aggression against Ukraine, which has provided Poland with a salutory reminder of the importance of robust defenses. With its choice of the A26 class, Poland will be getting one of the most capable conventionally powered submarines available and making another statement about how strongly it takes its defense.

Contact the author: [email protected]