Deadly drone attacks on civilians continue in Sudan’s Kordofan, UN says | Sudan war News

United Nations human rights chief also decries ‘preventable human rights catastrophe’ in Sudan’s el-Fasher.

Published On 9 Feb 2026

Fatal drone strikes on civilians persist in Sudan’s Kordofan, as the central region has emerged as the latest front line in Sudan’s nearly three-year conflict, the United Nations has said.

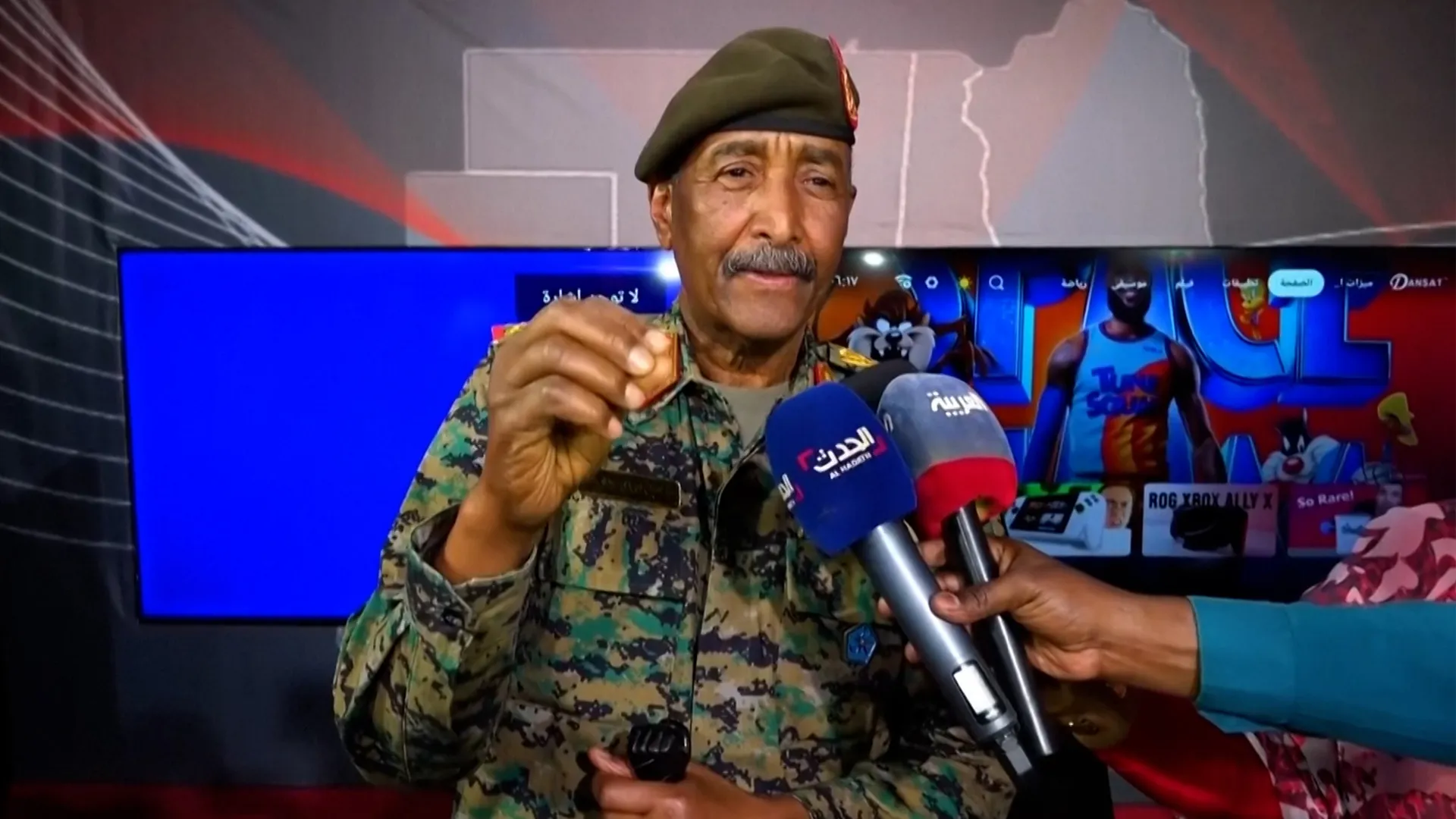

Addressing the Human Rights Council in Geneva on Monday, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Turk painted a grim picture of the conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which has plunged the country into widespread bloodshed and humanitarian catastrophe.

Recommended Stories

list of 3 itemsend of list

“We can only expect worse to come” unless decisive steps are taken by the international community to stop the fighting, Turk said, emphasising that inaction would lead to even greater horrors.

Turk also highlighted harrowing survivor testimonies from el-Fasher, the capital of North Darfur, which fell to RSF forces in October following an 18-month siege. He described accounts of atrocity crimes committed by the paramilitary after it overran the city, including mass killings and other grave violations targeting civilians.

“Responsibility for these atrocity crimes lies squarely with the [RSF] and their allies and supporters,” he said

As Sudan’s devastating civil war expands beyond the western Darfur region into the central Kordofan areas, Turk cautioned that the shift in fighting is likely to bring even more severe violations against civilians, expressing deep concern over the potential for additional grave abuses, specifically highlighting the increasing use of “advanced drone weaponry systems” by both warring parties.

“In the last two weeks, the SAF and allied Joint Forces broke the sieges on Kadugli and Dilling,” Turk said. “But drone strikes by both sides continue, resulting in dozens of civilian deaths and injuries.”

Turk’s office has documented more than 90 civilian deaths and 142 injuries caused by drone strikes carried out by both the RSF and the armed forces from late January to February 6, he said.

Among those incidents were three strikes on health facilities in South Kordofan that killed 31 people last week, according to the World Health Organization.

On February 7, a drone attack carried out by the RSF hit a vehicle transporting displaced families in central Sudan, killing at least 24 people, including eight children, the Sudan Doctors Network said.

The latest attacks follow a series of drone attacks on humanitarian aid convoys and fuel trucks across North Kordofan.

The UN human rights chief said he has witnessed the destruction caused by RSF attacks on Sudan’s Merowe Dam and its hydroelectric power station.

“Repeated drone strikes have disrupted power and water supplies to huge numbers of people, with a serious impact on healthcare,” he said.