N. Korea’s Spy Agency a ‘Complex Threat’ Beyond Intelligence Role

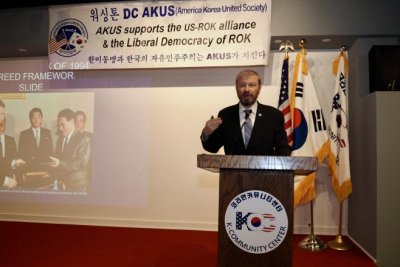

Greg Scarlatoiu, executive director of the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, speaks at an event hosted by the Washington chapter of the Korean American Union Society at the Washington Korean Community Center in Alexandria. File. Photo by Asia Today

Feb. 26 (Asia Today) — North Korea’s Reconnaissance General Bureau operates as a “complex threat entity” that merges military operations, cybercrime and terrorism under a single command structure reporting directly to leader Kim Jong Un, according to a new report from a Washington-based human rights organization.

The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea released the report Sunday, titled Reconnaissance General Bureau: The Kim Regime’s Precious Treasured Sword. It offers one of the most detailed public examinations to date of the agency’s structure, financing and global reach.

The report was authored by Robert Collins, a former U.S. Army strategist with extensive Korea-related experience, including serving as chief of strategy at the ROK-U.S. Combined Forces Command – the joint military structure that oversees the defense of South Korea.

Collins argues that the RGB defies easy comparison to conventional intelligence agencies. Unlike South Korea’s National Intelligence Service or the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, which operate within defined mandates, the RGB consolidates military reconnaissance, special operations, cyberwarfare, espionage, psychological operations and operations targeting South Korea under one centralized chain of command.

The bureau reports to North Korea’s State Affairs Commission and ultimately to Kim Jong Un, who the report says treats it as a core instrument of regime survival. Kim has personally referred to its cyber units as a “precious treasured sword,” according to the report.

Seven Bureaus, One Command

Established in February 2009 through the merger of several intelligence and operations units, the RGB currently operates through six main bureaus and a seventh logistics unit.

The first bureau oversees agent training and infiltration missions. The second conducts military reconnaissance along the Demilitarized Zone and coastal areas. The third manages overseas intelligence and alleged international operations. The fourth handles inter-Korean dialogue and related policy support. The fifth directs cyber operations, including hacking and communications interception. The sixth provides technical support and electronic warfare capabilities, while the seventh handles rear services and logistics.

Taken together, the report assesses that the RGB maintains operational capacity across land, sea, air and cyberspace – a multi-domain reach that few comparable organizations possess.

Cyber Operations as a Revenue Engine

A substantial portion of the report is devoted to North Korea’s cyber activities, which Collins describes as both strategically and financially central to the regime.

The report estimates that North Korea maintains approximately 5,900 cyber personnel and identifies hacking groups Lazarus, Andariel and Bluenoroff as operating under the RGB’s organizational umbrella. These groups have been linked by U.S. and international authorities to some of the most significant state-sponsored cyberattacks in recent years.

Drawing on international assessments, the report alleges that North Korean-linked hackers stole approximately $1.7 billion in cryptocurrency in 2022 alone – funds it says are funneled into the country’s nuclear and missile programs, helping Pyongyang sustain its weapons development despite sweeping international sanctions.

The report also raises concern about reported cooperation between North Korean operatives and foreign cybercriminal networks, suggesting the bureau’s reach may extend further into the global criminal ecosystem than previously documented.

Human Rights in the Crosshairs

The report draws an explicit connection between the RGB’s security operations and human rights, an angle that sets it apart from purely strategic assessments of the bureau.

It argues that cyber intrusions, surveillance and information disruption campaigns may violate international covenants protecting privacy and freedom of expression. It further contends that revenue generated through cybercrime – redirected to weapons programs rather than civilian welfare – could breach obligations under international agreements on economic and social rights.

The report also revisits a series of past incidents attributed to North Korean operatives, including armed infiltrations, bombings and assassinations, characterizing them as violations of the right to life and other fundamental protections under international law.

A Threat Beyond the Peninsula

In its conclusion, the report warns that the RGB can no longer be viewed solely as a regional security concern. The integration of its cyber capabilities with emerging technologies – including drones and advanced reconnaissance systems – could significantly complicate the security environment in coming years, the report said.

The committee said the study is intended as a reference for policymakers, researchers and security specialists seeking to understand the bureau’s expanding operational scope.

No response from the North Korean government was immediately available. Pyongyang does not typically comment on reports issued by foreign organizations.

— Reported by Asia Today; translated by UPI

© Asia Today. Unauthorized reproduction or redistribution prohibited.

Original Korean report: https://www.asiatoday.co.kr/kn/view.php?key=20260226010007781