Changing Venezuela’s Amnesty Law to Address Decades of Repression

Venezuela’s National Assembly has passed an amnesty law amid the political, economic, and social shifts the country has been experiencing following the removal of Nicolás Maduro by the United States. On February 5, the first debate on the amnesty bill took place, and after two weeks of consultations it was unanimously approved on February 19. Although the law includes significant changes compared to the version approved in the first stage, it still contains gaps that make it impossible to speak of genuine reconciliation.

Throughout the entire process, the ruling party’s narrative has been that chavismo “forgives” those who committed crimes, rather than acknowledging that the judicial system acted in a biased, arbitrary manner and contrary to the law. This is important to underscore because amnesty laws arise as special justice mechanisms through which the State recognizes its partial use of the justice system, especially in political contexts.

This newly approved amnesty law cannot be perceived as a sign of reconciliation. On the contrary, it seems to be a mechanism that allows the Rodríguez siblings to manage the release of prisoners without recognizing the State’s responsibility for more than two decades of political persecution. At the same time, however, we must view the consultation processes—promoted from within the structures of chavista power—as spaces where sectors of civil society and civic organizations raised their voices and, in one way or another, managed to be “heard” and “taken into account” to some extent.

To “forgive” prisoners, the presidency already has the authority to decree pardons under Article 236 of the Venezuelan Constitution. If the Executive Power is already able to order releases, what function does this law actually serve?

The answer to that question reveals the structural insufficiency of the law that was passed. It establishes no mechanisms for reparation and continues to exclude hundreds of individuals who have been persecuted. At its core, the law does not correct injustice. It merely attempts to cloak in legality the discretionary manner in which power has exercised persecution. It follows the same logic that has been used for years with pardons (the last of which came on Christmas 2025, days before the US military intervention) which are presented as gestures meant to project a “goodwill” image of the State while avoiding any acknowledgment of the harm caused.

Changes and silences

From the outset, we expected an imperfect law that would at least have room for improvement. In that regard, the law introduced important changes compared to the draft approved in the first debate, such as providing legal representation for those abroad. It also revised the list of excluded crimes, narrowing it to the crime of corruption (previously referred to as “crimes against public assets”), incorporated the possibility of appeals against court decisions on amnesty, and ordered notification to foreign bodies to lift international alerts or arrest warrants. It can even be said that it broadened the scope of acts eligible for amnesty. However, it also made significant omissions.

The statute could be amended to create a commission entirely independent from State bodies, composed of representatives of civil society, relatives of victims, and experts capable of making binding decisions.

The law must include all persecuted individuals. There can be no distinctions or exclusions, because persecution itself made no such distinctions. For this reason, any meaningful improvement of the current law must begin by eliminating the exclusion set out in Article 9 concerning “persons who are or may be prosecuted or convicted for promoting, instigating, requesting, invoking, favoring, facilitating, financing, or participating in armed or forceful actions against the people, the sovereignty, and the territorial integrity of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, on behalf of States, corporations, or foreign individuals.” If the crime of rebellion is generally defined as an uprising against authority, then it is a political act like any of the other amnestiable offenses.

Recognition, inclusion, and non-discrimination must be the minimum standards for any amnesty that seeks to be considered a step forward in the pursuit of justice.

Lacking external oversight

In transitional justice contexts, international frameworks are clear in their assessment of amnesties: they cannot be left in the hands of the very institutions that participated in the persecution. The approved law establishes that verification of amnestiable cases falls to the courts and the Public Prosecutor’s Office, whose highest-level official stated in November 2024 that there were no political prisoners in Venezuela (nor minors unjustly imprisoned), only individuals who committed crimes and were prosecuted in accordance with the law. This underscores a problem as obvious as it is serious: this amnesty law cannot, on its own, correct the very bodies responsible for human rights violations.

The final text incorporates an advisory body to monitor the law’s implementation, one of the recommendations made by experts who engaged with the Interior Policy Commission. This body takes the form of a Special Commission of the National Assembly composed of figures directly linked to the State’s control and coercive apparatus, including Nicolás Maduro Guerra and Iris Varela, the former Minister of Prisons.

To ensure impartiality and credibility, oversight of the law’s implementation should fall to an independent body. Given that Venezuela lacks a genuine separation of powers, the statute could be amended to create a commission entirely independent from State institutions, composed of representatives of civil society, victims’ families, and experts in human rights and transitional justice, with powers to review case files, request information, and make binding decisions. In other words, technical specialists must be able to effectively oversee the application of the law.

Memory and non-repetition

If we aspire for the amnesty law to contribute to Venezuela’s reconciliation process, it cannot be limited to releasing individuals. The law must repair the harm caused and guarantee that persecution will not occur again.

Article 14 maintains the elimination of records and criminal histories of beneficiaries. This provision, far from promoting reconciliation, may erase evidence necessary to reconstruct patterns of persecution. Preserving documentation is a cornerstone of transitional justice. An amnesty that erases archives risks becoming a mechanism of impunity. Thus, while cases must indeed be extinguished, the files should be preserved and made available so that the Commission responsible for verifying the amnesty can confirm that victims have been repaired.

The discussion is no longer about whether persecution occurred, but about how it will be repaired and what independent mechanisms are needed to review each case.

Moreover, the law does not prescribe any mechanism for reparation. But all of this depends on the State recognizing its victims, restoring their rights, providing both symbolic and material reparations, and adopting institutional reforms that serve as safeguards to prevent the justice system from once again being used in a partisan manner.

One element removed from the draft approved in the first debate was the extinction of administrative actions. While this may seem minor, in the Venezuelan context it is vital. Amnesty should not apply only to criminal cases. In Venezuela, administrative mechanisms—such as political bans on opposition figures—have been used arbitrarily and constantly

Without these elements, the amnesty risks becoming a clean slate rather than a commitment to truth, justice, and non-repetition.

Political signals

The US has not issued a statement on the approved law. Representatives of the Trump administration, including the president himself, have primarily insisted on the release of political prisoners and the safe return of those in exile. We will see whether there is a statement (which, in my view, will come and will amount to a “green light”) and whether this law fits within the steps announced by Washington to evaluate the conduct of those in charge of the Venezuelan government.

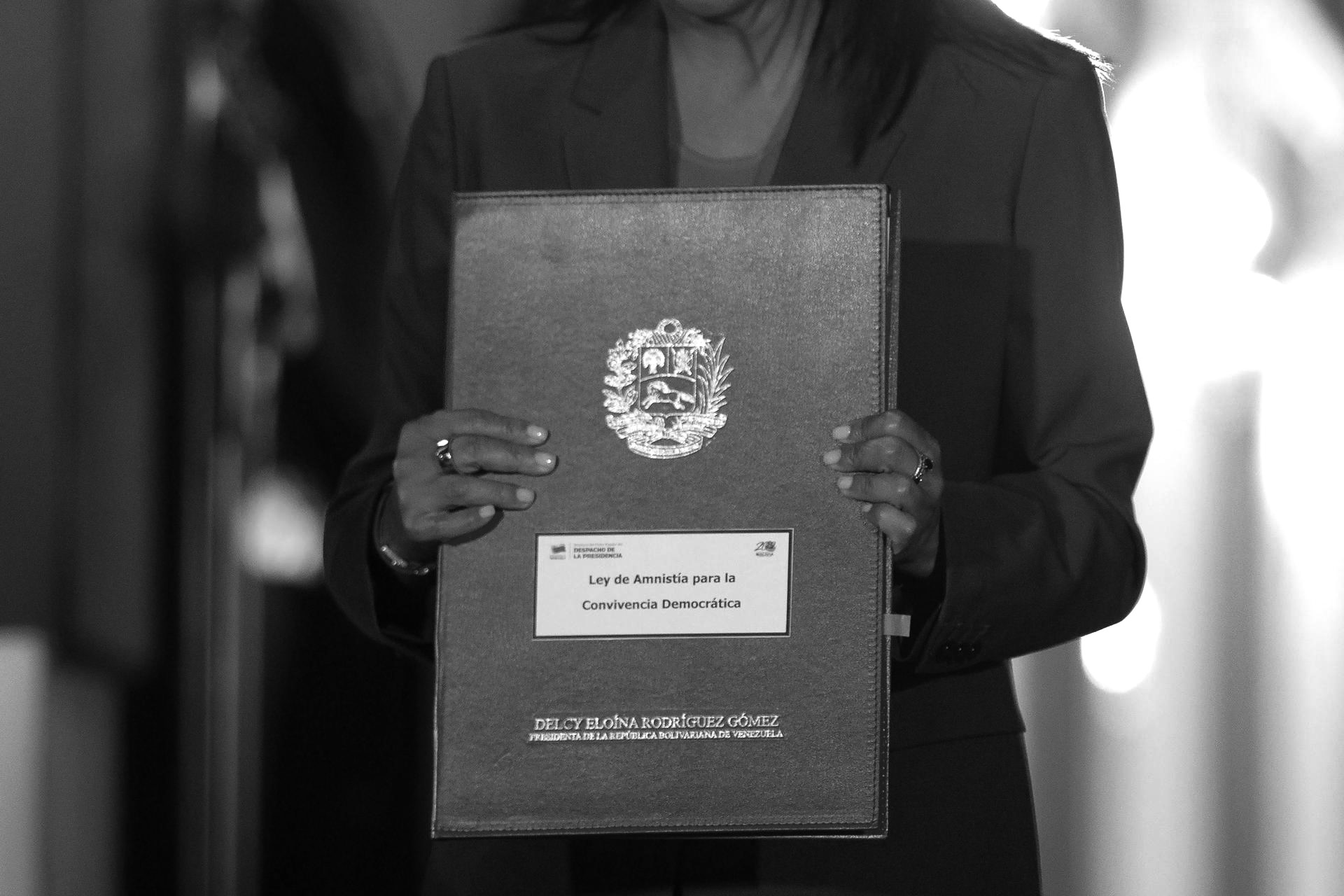

After the law was approved in the chamber, lawmakers immediately presented it to the Executive. Delcy Rodríguez signed it publicly and, in her speech, called for speed in evaluating cases that do not fall under the law. That call can take several paths: issuing final convictions, granting pardons, or decreeing dismissals. The difference among the three is enormous. The first would mean completely forgetting those who are not amnestiable and keeping them imprisoned; the second would amount to a simple pardon, without acknowledging injustice; and the third would be an admission that there is insufficient evidence to proceed.

Jorge Rodríguez’s statements are also important to note: he publicly acknowledged the unjust application of the Anti-Hate Law and the possibility of reforming it. He also recognized that there are more than 11,000 cases linked to political persecution. That acknowledgment, although it did not come with an admission of responsibility, dismantles the narrative that these are “isolated” incidents or that the amnesty concerns only “individual cases.” Whether this is a gesture of “democratization” or simply the result of international oversight now conditioning the government, admitting the magnitude of persecution creates a crack in the official discourse. A crack that civil society and the opposition must seize.

When we speak of reconciliation and pacification in Venezuela, we mean that it’s the State that must cease to be a violent actor. Today, with an insufficient amnesty law in place, we cannot speak of such reconciliation. But considering these signals, the discussion is no longer about whether persecution occurred, but about how it will be repaired and what independent mechanisms are needed to review each case.

Venezuela needs real reconciliation. And such reconciliation is only possible if the State acknowledges that it systematically used the justice system to persecute those who think differently. The approved law is insufficient, but it may yield partial results. That is why it is important for civil society to be present at every public forum to demand truth, reparation, and review of case files. The more contradictions those interventions induce among powerful factions, the greater the pressure to make decisions that would not be made voluntarily. This amnesty law does not resolve persecution, but it does create a space for persistence, oversight, and civil society coordination that can push for real change. As the transition advances and the political landscape shifts, the amnesty law can be adjusted, expanded, and corrected. Its enactment is not an endpoint. It is a starting point that can evolve.