How this author joined the crews fighting California’s wildfires

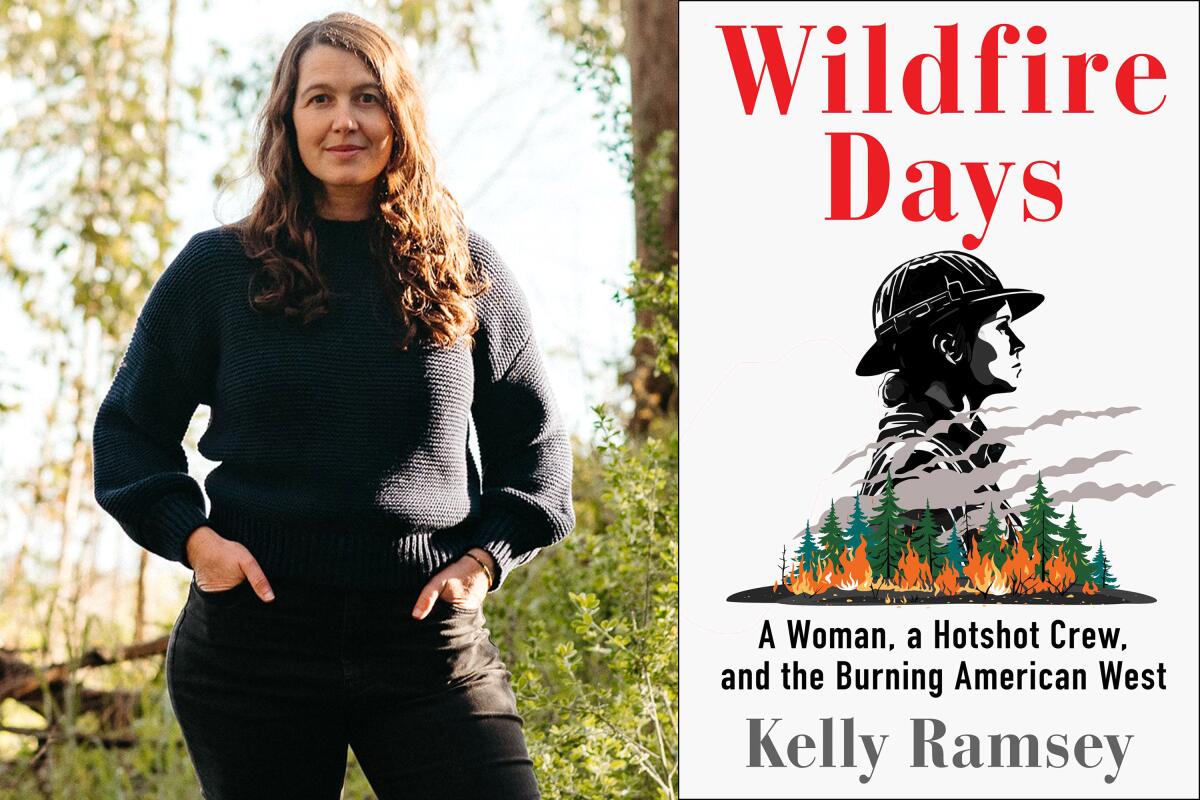

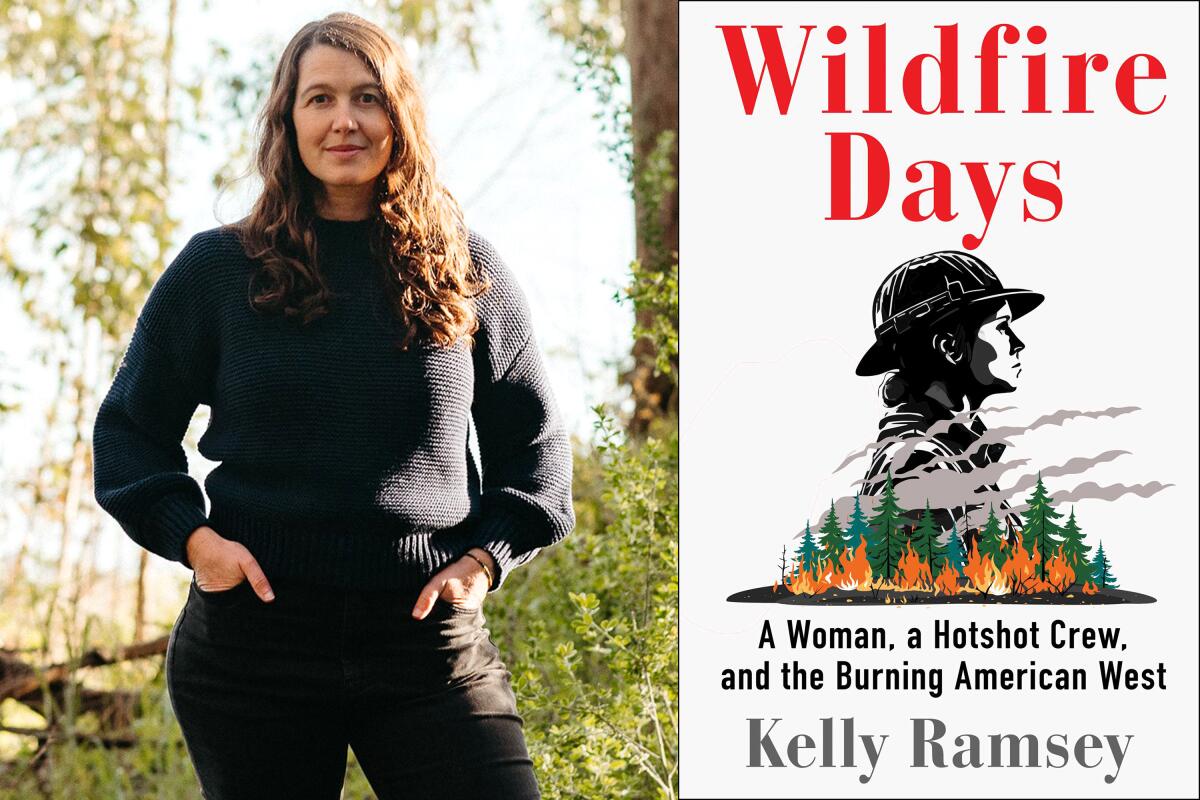

This week, we are jumping into the fire with Kelly Ramsey. Her new book, “Wildfire Days: A Woman, A Hotshot Crew, and The Burning American West,” chronicles her time fighting some of the state’s most dangerous conflagrations alongside an all-male crew of Hotshots. The elite wildland firefighters are tasked with applying their tactical knowledge to tamp down the biggest fires in the state. We also look at recent releases reviewed by Times critics. And a local bookseller tells us what our next great read should be.

In 2017, Ramsey found herself in a holding pattern. Living in Austin, with an MFA from the University of Pittsburgh under her belt, she didn’t know what or where she wanted to be. So she took a nanny job. “I was spending all my time outdoors with these kids,” she told me. “I thought, is there a job that would allow me to be outside all the time?”

Ramsey landed a volunteer summer gig working on a fire trail crew in Happy Camp, Northern California, on the Klamath River. While Ramsey was learning the delicate art of building firebreaks, a large fire broke out just outside the town. “My introduction to California that summer was filled with smoke,” says the author. “This is when I got the bug, when I started to become interested in fighting fires.”

Ramsey became a qualified firefighter in 2019, joining an entirely male crew of fellow Hotshots. Ramsey’s book “Wildfire Days” is the story of that fraught and exciting time. We talked to Ramsey about the “bro culture” of fire crews, the adrenaline surge of danger and the economic hardships endured by these frontline heroes.

Below, read our interview with Ramsey, who you can see at Vroman’s on June 23. This Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

(Please note: The Times may earn a commission through links to Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.)

✍️ Author Chat

Ramsey details how she became a qualified firefighter in 2019, when she joined an entirely male wildland fire crew, in her new book.

(Lindsey Shea; Scribner)

What was it like when you confronted a big fire for the first time?

It was the Bush fire in Arizona. I was so incredulous, just marveling at what was happening. “Look at that smoke,” and “that helicopter is making a water drop.” It was kind of a rookie move, because all the other crew members had seen it thousands of times. To see a helicopter up close making a drop, it looks like this gorgeous waterfall. I had to get acclimated to the epic nature of fires. And that wasn’t even a big fire, really.

In the book, you talk about entering into a pretty macho culture. How difficult was it for you to gain acceptance into this cloistered male world of the fire crew?

It was definitely shocking at first, to be in an entirely male space. The Forest Service had some sexual harassment scandals in 2017, so everyone was on their best behavior at first. It took me some time before I was accepted into the group. I had to perform over-the-top, irrefutably great, just to prove to them that I was OK. It’s an unfair standard, but that’s the way it was. I wanted to shift the way they saw women, or have better conversations about gender and fire.

You write about the pride and stoicism of the fire crew members, the ethos of actions rather than words. No one brags or whines, you just get on with it. Why?

When my editor was going through the book, he insisted that I mention the 75 pounds of gear I was always carrying on my back, and I resisted, because you don’t complain about that kind of thing when you’re out there. But I realized that readers would want to know these details, so I put them in. I was inclined to leave them out.

You also write about the difficulties of re-entering civilian life.

I don’t know of any firefighters who don’t struggle with the idea of living a normal, quiet life. It’s just a massive letdown after the adrenaline rush of the fire season.

What was shocking to me reading “Wildfire Days” is that fire crews are essentially paid minimum wage to work one of the most dangerous jobs in the state.

It was $16.33 an hour when I was in the crew. And most firefighters that I worked with didn’t have other jobs. They would take unemployment until the next fire season rolled around. You would just scrape by. During the first month of the season, everyone would be flat broke, eating cans of tuna. The joke is that you get paid in sunsets. But we all love being out there. The camaraderie is so intense and so beautiful.

📰 The Week(s) in Books

In this vintage photo, a man walks in front of the Italian Hall, constructed in 1908; all the structures on the block behind him have been demolished. A new book looks at Los Angeles in this time period.

(Angel City Press at the Los Angeles Public Library)

Hamilton Cain reviews National Book Award winner Susan Choi’s new novel, “Flashlight,” a mystery wrapped inside a fraught family drama. “With Franzen-esque fastidiousness,” Cain writes, “Choi unpacks each character’s backstory, exposing vanities and delusions in a cool, caustic voice, a 21st century Emile Zola.”

Jessica Ferri chats with Melissa Febos about her new memoir, “The Dry Season,” about the year she went celibate and discovered herself anew. Febos wonders aloud why more women aren’t more upfront with their partners about opting out of sex: “This radical honesty not only benefits you but it also benefits your partner. To me, that’s love: enthusiastic consent.”

Carole V. Bell reviews Maria Reva’s “startling metafictional” novel, “Endling,” calling it “a forceful mashup of storytelling modes that call attention to its interplay of reality and fiction — a Ukrainian tragicomedy of errors colliding with social commentary about the Russian invasion.”

Nick Owchar interviews Nathan Marsak about the reissue (from local publisher Angel City Press) of “Los Angeles Before The Freeways: Images of an Era, 1850-1950,” a book of vintage photos snapped by Swedish émigré Arnold Hylen and curated by Marsak. Owchar calls the book “an engrossing collection of black-and-white images of a city in which old adobe structures sit between Italianate office buildings or peek out from behind old signs, elegant homes teeter on the edge of steep hillsides, and routes long used by locals would soon be demolished to make room for freeways.”

And sad news for book lovers everywhere, as groundbreaking gay author Edmund White died this week at 85.

📖 Bookstore Faves

Diesel, A Bookstore manager Kelsey Bomba tells us what’s flying off the shelves at the Westside bookseller.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

This week, we paid a visit to the Westside’s great indie bookstore Diesel, which has been a locus for the community in the wake of January’s Palisades fire. The store’s manager, Kelsey Bomba, tells us what’s flying off the store’s shelves.

What books are popular right now:

Right now, Ocean Vuong’s “The Emperor of Gladness” is selling a ton, as [well as] Miranda July’s “All Fours” and Barry Diller’s memoir, “Who Knew.”

What future releases are you excited about:

Because I loved V.E. Schwab’s “The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue,” I’m excited to read her new book, “Bury Our Bones in the Midnight Soil.” “The Great Mann,” by Kyra Davis Lurie — we are doing an event with her on June 11.

What are the hardy perennials, the books that you sell almost all the time:

“One Hundred Years of Solitude” by Gabriel García Márquez, Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson series and the Elena Ferrante books, especially “My Brilliant Friend.”

Diesel, A Bookstore is located at 225 26th St., Suite 33, Santa Monica CA 90402.