India-China Rapprochement: Between Pragmatic Engagement and Enduring Skepticism

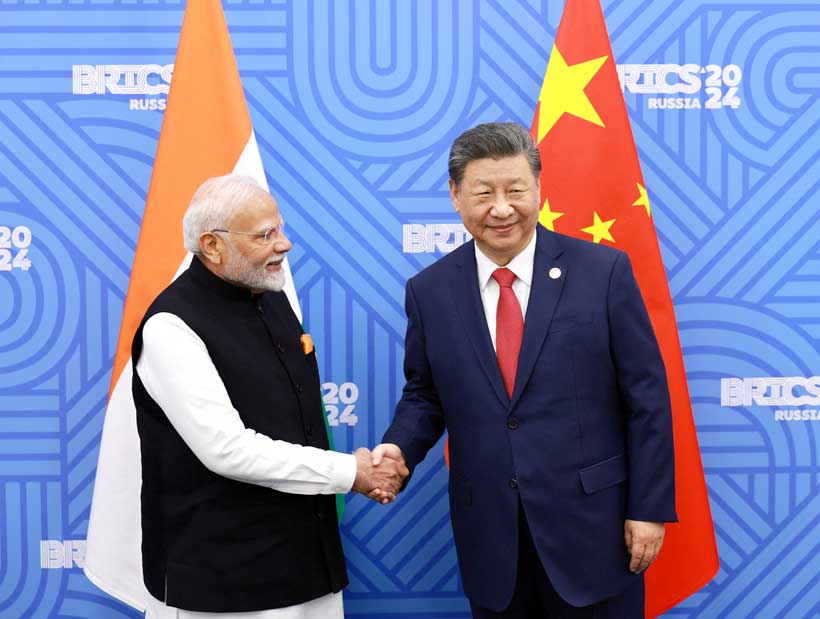

Lord Palmerston’s maxim that “We have no eternal allies nor perpetual enemies. “Our interests are eternal and perpetual,” aptly describes the rapidly changing nature of India-China relations. Border strife has been the norm between the two nations for decades, shaping their strategic stances. However, October 2024 saw a minor thaw in relations, with New Delhi and Beijing coming to terms with a major agreement on patrolling protocols along the disputed LAC. This breakthrough led to a series of high-level diplomatic engagements in a carefully measured but pragmatic manner. More importantly, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping engaged in direct bilateral talks at the BRICS Summit in Kazan, which was followed by a defense ministers’ conversation during the ASEAN Defense Ministers’ Meeting in November. The momentum then carried over into December in the form of the revival of the India–China Special Representatives Meeting, one of the important strategic platforms that had been asleep for five years. Although these developments do not eliminate deeply ingrained strategic distrust, they demonstrate a realist convergence; both nations are putting national interests ahead of ideological or historical animosities, embracing engagement rather than isolation as a way to manage competition and maintain regional stability.

In August 2025, Mr. Wang Yi, China’s Foreign Affairs Minister, visited India after three years for the improvement of the relationship between the two nuclear and emerging regional states. During his stay in India, Wang Yi co-chaired the 24th round of the Special Representatives’ Dialogue on the Boundary Question between India and China with the National Security Advisor, Ajit Doval. He also had bilateral discussions with Minister of External Affairs S. Jaishankar and met Prime Minister Modi. His visit after the 2020 Galwan clashes between India and China primarily concentrated on bilateral issues like border stabilization, economic cooperation, and regional security.

Therefore, Mr. Wang Yi’s visit to India marks a recalibration of ties based on a healthy and stable India-China relationship that serves the long-term interests of both countries.Secondly, the visit preceded PM Modi’s trip to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in Tianjin, his first visit in seven years, thereby laying the groundwork for stronger bilateral engagements. Thirdly, the visit came at a crucial time, as both countries face pressure from shifting US trade orientations, resulting in a push for pragmatic recalibration of ties and a strategic embrace on both sides.

However, during the month of February 2025, the Indian government ordered the erasure of 119 Chinese applications from the Google Play Store and, by June, announced a five-year tariff on imports of Chinese industrial inputs, which read as putting up a false facade of resistance against Beijing. However, the most compelling contrast comes from the diplomatic posture of India; calling for normalization with China while acting tough on them quite literally sounded like shouting at a neighbor while still borrowing sugar from them. Abandonment by America becomes evident for Modi; therefore, his choice of dialogue with Beijing reinforces both strategic weakness and duplicitous diplomacy. After many years during which warnings on Chinese expansionism were issued, the border may remain tense, but New Delhi seems determined to maintain good relations with China. This very decision of shaking hands underscored India’s inability to match China on political, strategic, and economic fronts. Meanwhile, Wang Yi’s parallel visits to Pakistan and Afghanistan highlight Beijing’s much broader regional priorities, reminding New Delhi just how far it is from being at the very center of China’s diplomacy.

The SCO Summit in Beijing saw the attendance of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who sought to mend ties between China and India after a period of tension; however, unresolved grievances cast serious doubts on the sustainability of this rapprochement. In the short term, ties may improve, since India has realized how great the necessity for cooperation with China has become in pushing its economic ambitions. This necessity to engage China more aggressively is driven especially in light of strained relations with the US under Trump’s steep tariffs. However, deep sensitivities on sovereignty and territorial integrity argue against any form of a sustainable relationship with China, beginning at the Sino-Indian border conflict and continuing through Arunachal Pradesh and Kashmir to China’s stance on Tibet. Mutual suspicion over regional engagements also exists, fueled by Beijing’s relations with Pakistan and New Delhi’s burgeoning naval cooperation in Asia. Contrasting language in the Modi–Xi meeting readouts, with India stressing a “multi-polar Asia” while China glossed over it, further reflects differing perspectives on the regional order. Through the stopover of Modi in Japan before going to Beijing and participation in the SCO Summit while skipping China’s Victory Day celebrations, it shows India’s cautious attempts to consolidate strategic autonomy, moving closer to both China and Russia while not disturbing the US or the West. If there is not any forward movement on the substantive disputes, the tensions will resurface in time, making any sustainable rapprochement between India and China again very unlikely, even if large-scale conflict does not seem to be a strong possibility.

In short, India and China may converge temporarily out of pragmatism, but without resolving core disputes, trust will remain elusive. New Delhi’s balancing act between Beijing, Washington, and Moscow highlights both its ambitions and vulnerabilities. Lasting peace requires more than symbolic summits—it demands substantive compromises on sovereignty, security, and regional influence. Until then, rapprochement will remain fragile, an uneasy truce rather than a genuine transformation.

![Police officers stand guard in front of the Tiananmen Gate, in an area temporarily closed to visitors due to construction, in advance of a military parade marking the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, in Beijing, China, on August 20, 2025 [Florence Lo/Reuters]](https://www.occasionaldigest.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/2025-08-25T084236Z_2025718761_RC2WAGAF3U1R_RTRMADP_3_WW2-ANNIVERSARY-CHINA-ARMS-1756523046.jpg)