Connie Francis, legendary singer of ‘Who’s Sorry Now?’ and ‘Where the Boys Are,’ dies at 87

Connie Francis, the angelic-voiced singer who was one of the biggest recording stars of the late 1950s and early 1960s, has died. She was 87.

Her friend and publicist, Ron Roberts, announced the singer’s death Thursday, according to the Associated Press.

A month prior to her death, Francis was hospitalized for “extreme pain” following a fracture in her pelvic area. The singer, who shared details about her health with fans on social media, used a wheelchair in her later years and said she lived with a “troublesome painful hip.”

Francis emerged when rock ’n’ roll first captivated America. Her earliest hits — a dreamy arrangement of the old standard “Who’s Sorry Now?,” the cheerfully silly “Stupid Cupid” and the galloping “Lipstick on Your Collar” — fit neatly into the emerging genre’s lighter side. Although she targeted teen listeners with such songs as the spring break anthem “Where the Boys Are,” Francis ultimately gravitated toward the middle of the road, singing softly lit, tasteful pop for adult audiences.

Francis’ commercial peak roughly spanned from Elvis Presley’s induction into the U.S. Army to the Beatles first setting foot on American soil. Over that five-year period, Francis was one of the biggest stars in music, earning three No. 1 hits: “Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool,” “My Heart Has a Mind of Its Own” and “Don’t Break the Heart That Loves You.” As her singles offered familiar adolescent fare, her albums were constructed for specific demographics. During the early ’60s, she cut records dedicated to “Italian Favorites,” “Rock ’n’ Roll Million Sellers,” “Country & Western,” “Fun Songs for Children,” “Jewish Favorites” and “Spanish and Latin American Favorites,” even recording versions of her hits in Italian, German, Spanish and Japanese.

This adaptability became a considerable asset once her pop hits dried up in the mid-’60s. Francis continued to be a popular concert attraction through the 1960s, her live success sustaining her as she eased into adult contemporary fare. A number of personal tragedies stalled her career in the 1970s, but by the ’90s, her life stabilized enough for her to return to the stage, playing venues in Las Vegas, Atlantic City and elsewhere until her retirement in the 2010s.

Connie Francis circa 1960.

(Archive Photos/Getty Images)

Connie Francis was born Concetta Maria Franconero on Dec. 12, 1938, in Newark, N.J. When she was 3, her father bought her an accordion and she spent her childhood learning Italian folk songs. By age 10, her parents enrolled her in local talent contests. When her father attempted to book her on the New York-based television show “Startime,” producer George Scheck only agreed because Francis played the accordion and he was “up to here in singers.” Francis remained a fixture on “Startime” through her early teens — Scheck served as her manager during these formative years — during which time she also appeared on Arthur Grodfrey’s “Talent Scouts.” Godfrey stumbled over her Italian name, suggesting she shorten it to something “easy and Irish,” thereby giving birth to her stage name.

Scheck managed to secure Francis a record contract with MGM in 1955. As she received work dubbing her singing voice for film actresses — she subbed for Tuesday Weld in 1956’s “Rock, Rock, Rock” and Freda Holloway in 1957’s “Jamboree” — MGM steadily attempted to move her from pop to rock. Nothing clicked until Francis recorded “Who’s Sorry Now?” as a favor to her father, giving the 1923 tune a romantic sway.

“Who’s Sorry Now?” caught the ear of Dick Clark, who regularly played the record on his “American Bandstand,” which had just expanded into the national market. Clark’s endorsement helped break “Who’s Sorry Now?” and sent it into the Billboard Top 10. MGM attempted to replicate its success by having Francis spruce up old chestnuts, but to no avail. The singer didn’t have another hit until she cut “Stupid Cupid,” a song co-written by Neil Sedaka and Howie Greenfield, a pair of young songwriters at the Brill Building who were navigating the distance separating Broadway-bound pop and rock ’n’ roll.

“Stupid Cupid” was the first of many hits she’d have with the songwriters, including the slinky ‘Fallin’” and the ballad “Frankie.” She later said, “Neil and Howie never failed to come up with a hit for me. It was a great marriage. We thought the same way.” Sedaka and Greenfield weren’t the only Brill Building songwriters to command Francis’ attention: She developed a romance with a pre-fame Bobby Darin, who was chased away by her father.

Over the next few years, Francis recorded both standards and new songs from Sedaka and Greenfield, along with material from other emerging songwriters, such as George Goehring and Edna Lewis, who wrote the lively “Lipstick on Your Collar.” Within less than two years, her popularity was such that MGM released five different Connie Francis LPs for Christmas 1959: a set of holiday tunes, a greatest-hits record, an LP dedicated to country, one dedicated to rock ’n’ roll and a set of Italian music, performed partially in the original language.

Connie Francis and Neil Sedaka in 2007.

(George Napolitano / FilmMagic / Getty Images)

With her popularity at an apex, Connie Francis made her cinematic debut in the 1960 teen comedy “Where the Boys Are,” which also featured a Sedaka and Greenfield song as its theme. Francis appeared in three quasi-sequels culminating in 1965’s “When the Boys Meet the Girls,” but she never felt entirely comfortable onscreen, preferring live performance. “Vacation” became her last Top 10 single in 1962 — the same year she published the book “For Every Young Heart: Connie Francis Talks to Teenagers.” Too young to be an oldies act, Francis spent the remainder of the 1960s chasing a few trends — in 1968, she released “Connie & Clyde — Hit Songs of the ’30s,” a rushed attempt to cash in on the popularity of Arthur Penn’s controversial hit film “Bonnie and Clyde” — while busying herself on a showbiz circuit that encompassed Vegas, television variety shows and singing for troops in Vietnam.

A comeback attempt in the early 1970s was swiftly derailed by tragedy. After appearing at Long Island’s Westbury Music Fair on Nov. 8, 1974, she was sexually assaulted in her Howard Johnson’s hotel room; the culprit was never caught. Francis sued the hotel chain; she’d later win a $2.5-million settlement that helped reshape security practices in the hospitality industry. As she was recovering from her assault, she underwent a nasal surgery that went astray, leading her to lose her voice for years; it took three subsequent surgeries before she regained her ability to sing. Francis spent much of the remainder of the ’70s battling severe depression, but once her voice returned, recordings happened on occasion, including a disco version of “Where the Boys Are” in 1978.

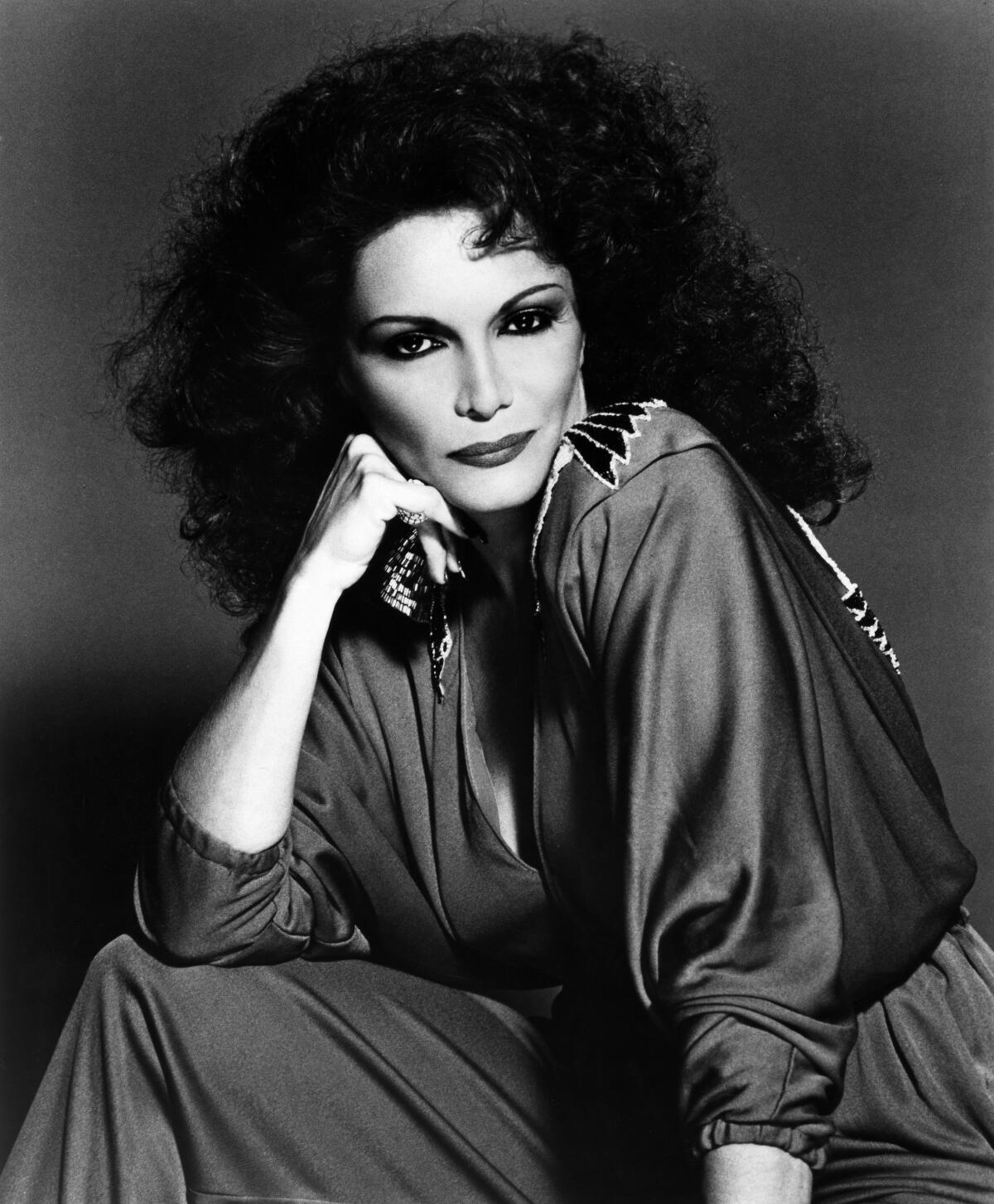

Connie Francis.

(ullstein bild via Getty Images)

Francis returned to the public eye in the early 1980s, first as a victims rights activist, then as a live performer. Her comeback was marred by further tragedy — the murder of her brother George, a lawyer who became a government witness after pleading guilty to bank fraud; the police indicated the killing was related to organized crime.

Francis continued to work in the wake of his death, playing shows and writing her 1984 autobiography, “Who’s Sorry Now?,” but she continued to be plagued with personal problems. She told the Village Voice’s Michael Musto, “In the ’80s I was involuntarily committed to mental institutions 17 times in nine years in five different states. I was misdiagnosed as bipolar, ADD, ADHD, and a few other letters the scientific community had never heard of.” After receiving a diagnosis for post-traumatic stress disorder, Francis returned to live performances in the 1990s; one of her shows was documented on “The Return Concert Live at Trump’s Castle,” a 1996 album that was her last major-label release. When asked by the Las Vegas Sun in 2004 if life was still a struggle, she responded, “Not for the past 12 years.”

Francis regularly played casinos and theaters in the 2000s as she developed a biopic of her life with Gloria Estefan, who planned to play the former teen idol. The film never materialized. In 2010, Francis became the national spokesperson for Mental Health America’s trauma campaign. By the end of the 2010s, she retired to Parkland, Fla., and published her second memoir, “Among My Souvenirs: The Real Story, Vol. 1,” in 2017.

Connie Francis married four times. Her first marriage, to Dick Kanellis in 1964, ended after three months; her second, to Izzy Marion, lasted from 1971 to 1972. She adopted a child with her third husband, Joseph Garzilli, to whom she was wed from 1973 to 1978. Her fourth marriage, to Bob Parkinson, ended in 1986 after one year.