How did China’s trade surplus hit $1 trillion? | Business and Economy News

China’s trade surplus – the difference between the value of goods it imports and exports – has hit $1 trillion for the first time, a significant yardstick in the country’s role as “factory of the world”, making everything from socks and curtains to electric cars.

For the first 11 months of this year, China’s exports rose to $3.4 trillion while its imports declined slightly to $2.3 trillion. That brought the country’s trade surplus to about $1 trillion, China’s General Administration of Customs said on Monday.

Recommended Stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

Shipments overseas from China have boomed despite US President Donald Trump’s global trade war, largely consisting of sweeping “reciprocal” tariffs on most countries, which were launched earlier this year in a bid to reduce US trade deficits.

But China, which was initially hit with US tariffs of 145 percent before they were lowered to allow for trade talks, has emerged largely unscathed from the standoff by stepping up shipments to markets outside the US.

Following Trump’s 2024 election win, China began diversifying its export market away from the US in exchange for closer ties with Southeast Asia and the European Union. It also established new production hubs, outside of China, for low-tariff access.

Why does China have such a large trade surplus?

China’s exports returned to growth last month following an unexpected dip in October, rising to 5.9 percent more than one year earlier and far outpacing a 1.9 percent rise in imports, according to China’s General Administration of Customs.

China’s goods surplus for the first 11 months of 2025 was up 21.7 percent from the same period last year. Most of the surge was driven by strong growth in high-tech goods, which outpaced the increase in overall exports by 5.4 percent.

Auto exports, especially for electric vehicles, rallied as Chinese firms muscled in on Japanese and German market share. Total car shipments jumped by more than one million to approximately 6.5 million units this year, according to data from China-based consultancy Automobility.

And although China still trails US leaders like Nvidia in advanced chips, it is becoming dominant in the production of semiconductors (used in everything from electric cars to medical devices). Semiconductor exports rose by 24.7 percent over the period.

China’s technological advances have also boosted shipbuilding, where exports rose 26.8 percent compared with the same period in 2024.

So, given the hostile global trade backdrop, how has China achieved this?

Rerouting and diversifying

Though Washington has lowered tariffs on Chinese imports in recent months, they remain high. Average import duties on Chinese goods currently stand at 37 percent. For this reason, Chinese shipments to the US have dropped by 29 percent year-on-year to November.

Some Chinese companies have shifted their production facilities to Southeast Asia, Mexico and Africa, enabling them to bypass Trump’s tariffs on goods arriving directly from China. Despite this, overall trade between the two countries remains down.

In the first eight months of this year, for instance, the US imported roughly $23bn in goods from Indonesia, an increase of nearly one-third on the same period in 2024. It is widely understood that the rise is down to Chinese goods being redirected via Indonesia.

“The role of trade rerouting in offsetting the drag from US tariffs still appears to be increasing,” Zichun Huang, an economist at Capital Economics, wrote in a note to clients on Monday. Huang added that “exports to Vietnam, the top [Chinese] rerouting hub, continued to grow rapidly.”

As trade with the US has slackened, China has doubled down on developing ties with other major trading partners. That includes a 15 percent surge in Chinese shipments to the EU, compared with the year before, and an 8.2 percent rise in exports to countries in Southeast Asia.

Weaker currency

Another reason for China’s trading success is that its currency has been cheap, compared with others, in recent years. A lower renminbi makes exports relatively inexpensive to produce, and imports relatively expensive to consume.

China maintains a “managed float” of the renminbi – meaning the central bank intervenes in foreign exchange markets to maintain its value against other currencies – with the aim of keeping the price stable.

For years, many economists have argued that China’s currency is undervalued. In their view, that gives exporters a competitive edge by boosting the appeal of cheap Chinese products at the expense of other countries, leading to large imbalances in trade.

Indeed, taking into account global inflationary dynamics, the real effective exchange rate – a measure of the competitiveness of Chinese goods – is actually at its weakest level since 2012.

How has China got here?

China’s eye-watering $1 trillion trade surplus – never before recorded in economic history – is the culmination of decades of industrial policies that have enabled China to emerge from a low-income agrarian society in the 1970s to become the world’s second-largest economy today.

China established itself as a dependable producer of low-cost manufactured goods, like T-shirts and shoes, in the 1980s. Since then, it has climbed the industrial ladder to higher-value goods, such as electric vehicles and solar panels.

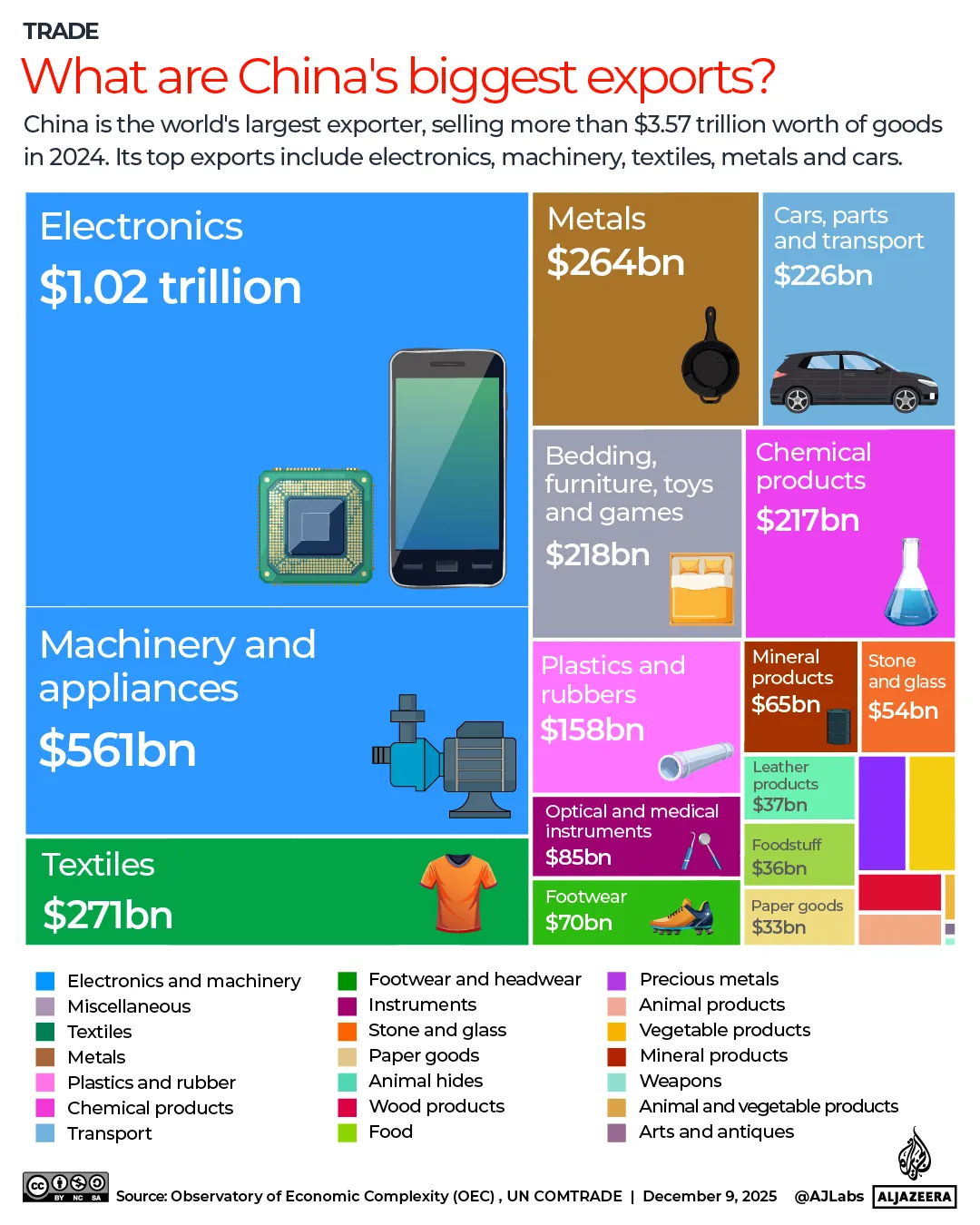

By far its largest sector in terms of exports is electronics. China exported a total of more than $1 trillion-worth of electronic goods around the world in 2024. This follows the pattern of other industrialised countries by starting with simple, labour-intensive goods and then moving into more complex sectors. However, China has done so with unusual scale and speed to cement its dominance across numerous global supply chains.

It also dominates trade in rare-earth metals, which are crucial for the manufacture of a wide range of goods from smartphones to fighter jets.

Twelve of the 17 rare earth metals on the periodic table can be found in China, and it mines between 60 percent and 70 percent of the world’s rare-earth resources. It also carries out 90 percent of the processing of these metals for commercial use.

For historical context, China’s trade surplus in factory goods is larger as a share of its economy than the US ran in the years after World War II, when most other manufacturing nations were emerging from the ruins of war.

How are other countries responding to China’s expanding dominance?

Many are looking for ways to redress the balance.

French President Emmanuel Macron, who visited China last week, warned the EU may take “strong measures”, including imposing higher tariffs, should Beijing fail to address the imbalance.

The EU already imposes additional tariffs on Chinese-made electric vehicles (EVs), which range from 17 percent to 35.3 percent, for example, on top of its existing 10 percent import duty.

Germany’s foreign minister, Johann Wadephul, arrived in China for a two-day trip on Monday this week, becoming the latest senior European official to visit for talks amid the country’s rapidly expanding goods trade with Europe.

Before his trip, Wadephul said he planned to raise the issue of tariffs with his Chinese counterparts, particularly those involving rare earths, in addition to concerns about industrial “overcapacities”, which he said are distorting global prices for industrial goods.

Will China’s exports continue to grow?

Despite efforts by the US and other wealthy countries to diversify away from China, few economists expect the country’s broad-based trade momentum to slow anytime soon.

Economists at Morgan Stanley predict China’s share of global goods exports will reach 16.5 percent by the end of the decade, up from 15 percent now, reflecting China’s ability to adapt quickly to shifting global demand.

More immediately, China’s strong trade performance means the annual growth target – set by Beijing to guide economic policy and to align regional governments – of about 5 percent is likely to be met.