One Friday afternoon in January, I was led to the Dogon Daji mining site in Gunda, Borno State, northeastern Nigeria. There were over 20 men there. Some prostrated in prayer, others ate, cross-legged on the bare earth. A few sat, seeking a moment of rest beneath the weight of the afternoon sun.

At the entrance, two young miners crouched over a pit, dragging out a sack securely tied with a rope, its bulging shape suggesting a large rock inside. The pit they pulled from was freshly dug. Around them, more pits—some new, others abandoned—scarred the earth like open wounds refusing to heal. I stepped closer and peered into the pit where they worked. It was deep—so deep that I could not see the bottom. Below, another miner toiled, his silhouette faint, a glint of light bouncing off his forehead where a lamp was strapped. He looked up, his voice rising through the shaft as he called for another rope. Without hesitation, they tossed one down.

Not far from where I stood, another miner, perhaps in his early thirties, emerged from a separate pit. He wore a faded green jersey, darkened with sweat and clinging to his body. When his eyes met mine, he gave a slight nod.

“Welcome,” he said, wiping a hand across his face. We had spoken earlier on the phone. Now, in person, he led me toward a hump of sand where we could talk.

“The majority of us here are graduates,” Hassan Mohammed said, squatting on the sand. “There are no jobs. Farming is no longer sustainable. And this mineral–blue sapphire–is abundant in the soil, available almost everywhere in the community.”

He leaned forward, dusting his hands against his faded trousers. His palms were rough, the skin cracked from years of labour. He had been mining for 15 years. What had started as a way to maximise his sources of income, something to do when farming slowed, had become a necessity.

“I never thought I would be here this long,” he admitted. “I studied Chemistry and Biology at the College of Education in Biu. I wanted to teach.” His gaze drifted towards the pits where other miners toiled under the sun. “But teaching does not put food on the table. This does.”

In the distance, another miner emerged from a pit, stretching his back before reaching for a cigarette from a bag on the ground. He lit it, took a slow drag, and exhaled before settling onto a nearby mound of earth.

Hassan’s expression remained solemn as he spoke, his fingers tracing patterns in the sand. “I have six children to feed,” he said. “During the rainy season, we farm, but farming alone is not enough. No government aid, no support from any organisation. So, we mine.”

“We are not civil servants. We are not businessmen. During the rainy season, you would not see us here. We will all be cultivating on our farms. But this is our only option once the dry season comes,” Hassan added.

At the mines, there is no certainty, no guarantee of profit. The price of the minerals depended on their purity, dictated by buyers in distant cities. “The finer ones sell for more,” Hassan explained. “Sometimes, a gramme goes for ₦150 [$0.099] or ₦200 [$0.13].” They sold to dealers in Gunda or transported the minerals to Jos, Bauchi, or Kano, where better prices awaited. But always, the buyers dictated the terms. The miners could only accept.

I asked about safety. Hassan let out a short laugh, shaking his head. “Protective gear?” The words seemed almost amusing to him. “We do not have any.”

The mines were merciless—pits dug by hand, nothing but crude tools and ropes standing between them and disaster: no helmets, no reinforced beams, no precautions. I scanned the landscape again: the endless pits, the men working tirelessly, the quiet resignation in their movements. They all understood the risks. At any moment, the earth beneath them could give way. Some had seen it happen. Some had not lived to tell the story.

I had seen the danger up close.

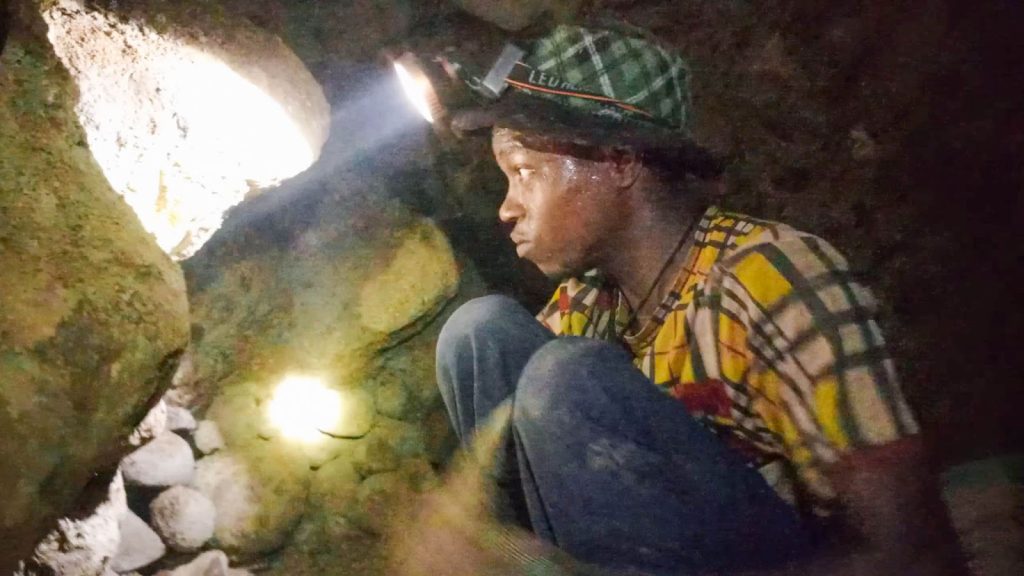

Shortly after my interview with Hassan, I climbed into one of the pits, crouching low—camera in my right hand, a lamp strapped to my forehead—as I spoke with Gidado, a young miner, inside. The air was thick with dust, the heat pressing like a second skin. He worked steadily, his torchlight flickering against the cave walls as he chipped away at the earth. Above us, a heavy rock he had wrapped in an old sack and secured with a rope was being hoisted up.

Then, suddenly, the sack tore.

The rock came crashing down.

It was a close shave, but for the miners, this was routine. They would dust themselves off, keep digging, and hope that today was not the day the earth claimed them.

The artisanal mining economy in Borno

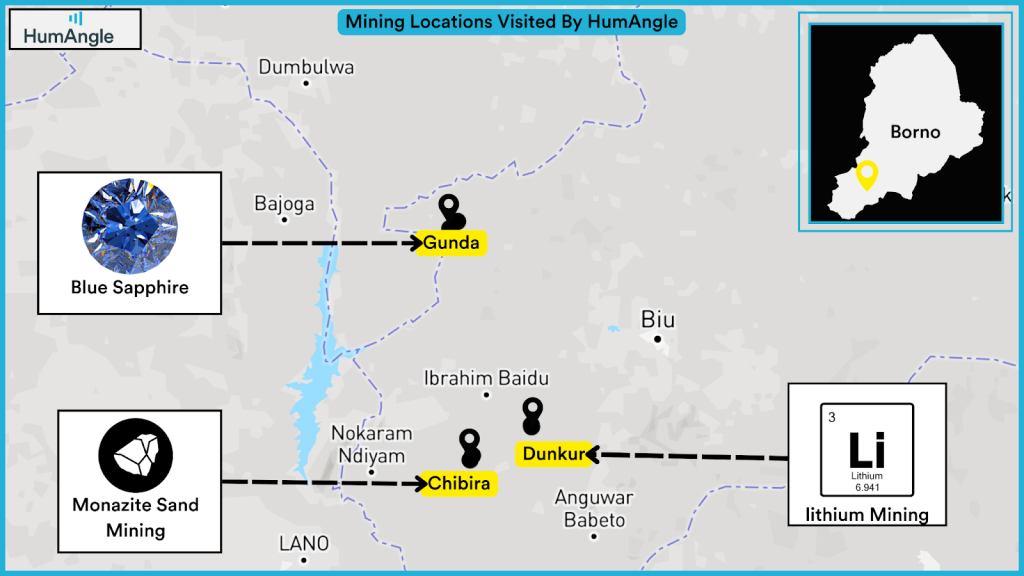

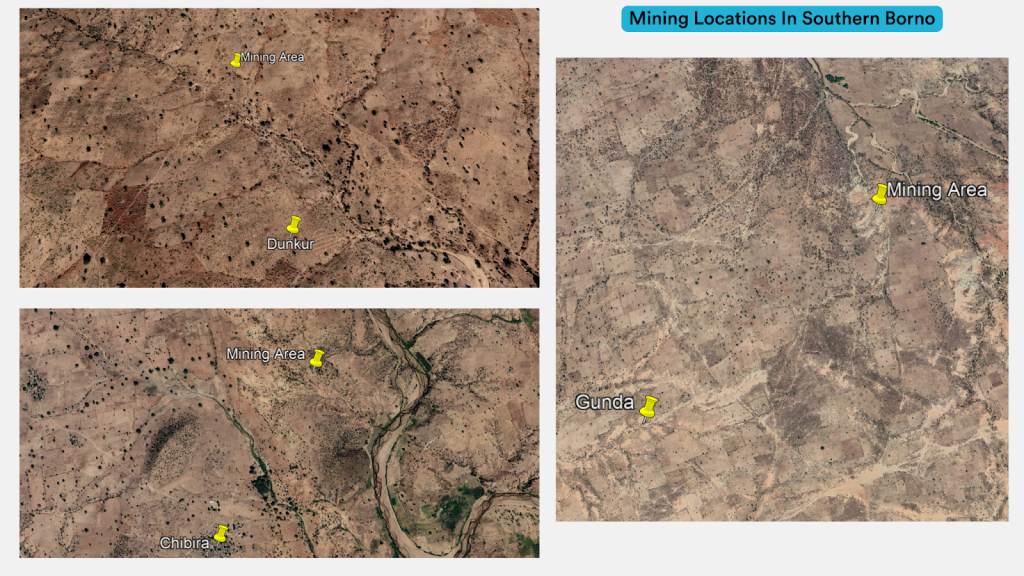

Before reaching Hassan in Gunda, HumAngle travelled across three other mining communities in Southern Borno—Chibra and Dunkur in Kwaya Kusar LGA and Bayo LGA—each with mineral wealth and its own story of struggle and survival.

In Chibra, the earth yields monazite sand—a mineral used in permanent magnets, phosphors for lighting and screens, catalysts, glass polishing powders, nuclear fuel (thorium), and specialised aerospace and defence alloys. The land also gives up fluorite, an essential mineral in refining hydrofluoric acid, aluminium smelting agents, optical lenses, gemstones for jewellery, flux for steelmaking, ceramics, and specialised glass.

Dunkur, on the other hand, is rich in lithium, a mineral increasingly sought after in global markets for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, glass and ceramics, lubricants, pharmaceuticals, aluminium alloys, air treatment systems, and even nuclear reactors.

Bayo shares Chibra’s deposits of monazite, while Gunda’s prize is blue sapphire, valued for its use in fine jewelry, watch crystals, optical components, semiconductor substrates, scientific instruments, and scratch-resistant windows for high-tech applications.

For most miners in Borno, the work is born out of necessity rather than choice. With few job opportunities and farming becoming increasingly unsustainable, mining, despite its dangers, remains one of the only ways to make a living.

“I grew up in a community of miners and saw how it sustained their livelihoods. So, I became a miner, too,” said Musa Abubakar, a 27-year-old monazite sand miner in Chibra. From sunrise to sunset, he and his fellow miners would work at the stream, meticulously washing away mud and sand to extract monazite. Their tools are crude—a shovel, a digger, a plastic container, and old cement bags spread flat on the riverbank to filter out the mineral. But even after the long hours and gruelling labour, they have little control over the value of their work. As in Gunda, prices are dictated by the dealers. “We sell a kilogramme at ₦700 [$0.47] and ₦1000 [$0.67],” Musa said, far below the mineral’s actual worth on the global market.

In Gunda, Suleiman Toro, a respected elder, has witnessed this cycle for decades. “Mining has been going on in this area for over sixty years,” he told me. He estimated that the region, with its 149 settlements, had up to 15,000 people engaged in mining, either directly or indirectly. While many are locals, others come from Jos, Bauchi, Lagos, and even neighbouring Cameroon and Niger Republic, drawn by the promise of minerals. But the real power lies elsewhere. The dealers—often outsiders—control the trade, set the prices, and reap the biggest profits, while the miners at the bottom of the chain struggle to survive.

‘Good farming seasons are rare’

Yet, Gunda is not just a mining town. It is, first and foremost, an agrarian community. Its people cultivate mostly grains and tomatoes. Maize and millet dominate the harvest, with some farmers producing up to 2,000 bags in a good season. But good seasons are becoming rare.

Suleiman, who studied environmental health at the College of Health in Maiduguri and now works at the primary healthcare center in Gunda, has seen the transformation firsthand. His harvest has declined—37 bags of maize and six bags of beans this season, a fraction of what the land once yielded. “The rains did not come as they used to,” he said. Climate change has made farming unpredictable and unstable. Mining has become the reluctant alternative for a community where agriculture was once a guarantee.

A 2020 report by the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI) estimated that artisanal and small-scale mining contributes significantly to local economies but remains largely undocumented in official records. In Borno alone, thousands rely on mining for their livelihood. The influx of buyers from different states and neighbouring countries underscores the sector’s economic significance.

Another report by NIETI indicated that Nigeria had 1,273 Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM) sites in 2020. Of these, 184 were in the northeast, making up 14.45 per cent of subsistence mining activities that year.

Despite its importance, government presence in these communities is almost nonexistent. “There are no projects here, either by the government or [non-governmental] organisations,” Suleiman said, frustration evident in his voice.

The roads are barely passable. Electricity is absent. Water comes from three boreholes—two solar-powered, one reliant on fuel. The community clinic, Comprehensive Health Centre (CHC), Gunda, struggles with limited resources. The primary school, Gunda Central Primary School, is one of the few educational institutions. The secondary school, however, ends at Junior Secondary Schoo level, forcing students to travel to Biu or Kwaya Kusar to continue their education.

Every Tuesday, the town springs to life on market day. Farmers and traders from Biu and Dadin Kowa arrive to buy and sell, but even here, climate change is making its mark—farm yields are shrinking, and food prices are rising. For many farmers, mining offers an alternative source of income. However, the long-term sustainability of this alternative remains questionable due to its environmental and health risks.

More risks

Across Nigeria and beyond, mining disasters have claimed countless lives, leaving entire communities in mourning. In 2024, at least 22 miners were buried alive when a pit collapsed at a mining site bordering Gashaka LGA in Taraba State and Toungo LGA in Adamawa State, northeastern Nigeria. The tragedy prompted the Minister of Solid Minerals Development, Dele Alake, to call for stronger collaboration between stakeholders and the National Parks Service to combat illegal mining and prevent further collapses.

Yet, the dangers of artisanal mining extend far beyond cave-ins. While miners in Gunda insist that pit collapses have not occurred in their area, the risks remain alarmingly high. Working without protective gear, miners constantly face the threat of suffocation, rock falls, and prolonged exposure to harmful substances.

The invisible dangers of mining are just as lethal. Long-term exposure to toxic dust and heavy metals poses severe health risks, even in communities where mining has existed for decades. A 2021 study analysing soil and crop samples from mining communities in Kwara State, North Central Nigeria, found elevated levels of arsenic, a highly toxic metal linked to cancer and organ failure. Similarly, in 2023, researchers tested water sources in Arufu, a mining community in Wukari, Taraba State, and found high concentrations of heavy metals, making the water unsafe for consumption.

The increasing presence of lithium mining in Nigeria introduces another layer of concern. A 2024 study indicates that lithium extraction depletes and contaminates water sources, worsening water scarcity and triggering severe health issues. The hazardous by-products of lithium mining, such as heavy metals and toxic chemicals, contribute to air pollution, environmental degradation, and respiratory illnesses.

Further studies have linked artisanal mining to respiratory diseases like silicosis and pneumoconiosis—both caused by inhaling fine mineral dust over extended periods. Lead poisoning, another grave consequence, has claimed the lives of hundreds of children in Zamfara, North West Nigeria, where gold mining contaminates entire villages. While Borno’s minerals differ, the risks remain—fluoride exposure, for instance, can cause severe skeletal deformities over time. A 2014 study found that dental fluorosis, marked by permanent staining and weakening of teeth, was widespread in fluoride-rich mining communities. The study recommended filtering drinking water through evaporation, a simple and cost-effective method adaptable to most Nigerian households.

Despite these dangers, safety measures are virtually nonexistent. Miners in Gunda admitted they take only rudimentary precautions: checking for cracks in the pits and looking for signs of animals or reptiles before entering. Helmets, masks, and reinforced supports remain unheard of.

Beyond health risks, artisanal mining has devastating environmental consequences. In Gunda, HumAngle visited four active mining sites—Dogon Daji, Aji Shiru, ATM, and Daban Hororo–all of which had deep, abandoned pits scattered across the terrain. Similarly, we noticed little vegetation cover–which Suleiman Toro attributed to activities of loggers and miners–which have stripped the land bare.

Yet, miners argue that their activities do not hinder farming. Hassan believes rainwater naturally fills abandoned pits during the wet season, making the land fertile again. “During the rainy season, the water washes the extracted soil and buries the pits,” he explained. Others nodded in agreement, reinforcing their belief that nature heals itself.

However, this notion is not only misleading—it is scientifically unfounded. As HumAngle travelled across the region, the landscape told a different story: Land that once sustained farming is now pockmarked with pits, stripped of fertility. “The land is no longer the same,” Suleiman Toro said. “We used to have fertile soil, but the pits left behind by miners make farming nearly impossible.”

A 2015 study on sapphire mining in Taraba reinforces these concerns, revealing that mining has generated wealth for some communities but has also led to severe environmental degradation. Entire forests have been lost, agricultural land has shrunk, and water sources have become polluted.

Women and children: The invisible workforce

Across the mining communities HumAngle visited, women and children do not descend into the pits; instead, they work in the streams, filtering minerals from stones. “There are a lot of women and children who come to the stream to filter,” said Musa Abubakar in Chibra. “You will see even more during the rainy season when the stream is full.” Buratai Yusuf*, a fluoride and monazite miner in Chibra, added, “Most of them are nine years and above. If a family has up to three children, the father may decide to farm while the children come to the stream to help with separation.”

In Gunda, this filtration process happens in a single stream. There, HumAngle met Ibrahim, a boy no older than ten, tirelessly sifting through sand and stone. His parents, who are in Gombe, had sent him to Borno as an Almajiri to acquire Islamic knowledge. Instead, he spends his days knee-deep in water, sorting through minerals alongside other children. His earnings—between ₦500 ($0.33) and ₦1000 ($0.67) daily—are just enough for food or basic necessities like soap to wash his clothes.

Borno’s situation is not unique. In Jir, a mining community in Bauchi, children like Suleiman endure the same daily grind. In Maru, Zamfara State, 15-year-old Abdulwahab Salisu spends his days mining gold instead of sitting in a classroom. Across Nigeria, entire generations are growing up not with books in their hands but with shovels, sieves, and the weight of survival on their shoulders.

For women, the struggle is different but no less punishing. Unlike men, who descend into the pits, they work on the periphery—gravel sifters, water carriers, food vendors—always on the margins, yet never untouched by the risks. Many are widows, divorcees, or displaced women with no other means of survival.

“They labour with their children at the streams, separating the extracted resources from other stones. Whatever they manage to gather, they sell to buy food,” Buratai said about the women in Chibra.

Unlike men, women do not dictate the trade—they exist within it, at the mercy of dealers who determine what their labour is worth. The income they earn is meager, influenced by the volume and quality of minerals they extract. Yet, without formal job opportunities or government support, this backbreaking work remains one of their only options for survival.

In many conflict-affected regions where artisanal mining thrives, reports of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) have emerged, with women and children often exploited in mining settlements. However, miners and women in Borno deny such claims. While the risk remains—given the lack of oversight and protection mechanisms—miners insist that economic hardship, not coercion or abuse, is what forces women and children into mining.

Even so, the unregulated nature of the industry leaves them vulnerable. With no government intervention, no formal labour protections, and no alternative means of income, these women and children remain invisible—statistical footnotes in the larger narrative of Borno’s mining economy.

‘No more mining in the state’

In 2023, the Borno State Government banned all mining activities, citing security concerns and the need to prevent mineral exploitation by terrorists. Officials argued that unregulated mining could serve as a funding stream for armed groups and announced plans to establish the Borno Mineral Resources Commission in Bayo to harness the state’s mineral wealth for job creation and economic stability.

The security concerns are not far-fetched. Across Nigeria, artisanal mining has been linked to the funding of armed groups. In neighbouring Taraba, reports indicate that illegal mining fuels kidnapping, terrorism, and boundary disputes between Taraba and Benue States. In Zamfara, terror leaders like 49-year-old Sani Black force villagers to work in illegally acquired mining sites in Tunani and Duka communities, funnelling the proceeds into organised crime and terrorism.

Yet, miners in Borno insist their reality is different. Unlike in Zamfara, where armed groups have seized control of mining operations, artisanal miners in Southern Borno insist that neither faction of the Boko Haram terror group—Jama’atu Ahlussunnah Lidda’awati Wal Jihad (JAS) nor the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP)—has ever subjected them to taxation.

“I have been in this profession for over 30 years, and there has never been a crisis over these resources. Similarly, no criminal, gang, or terror group is involved in the activities,” claimed Idrisa Ali*, a blue sapphire dealer in Gunda. Hassan confirmed this: “We are one community. There has never been conflict here.”

The terrorism taxation system is largely confined to the northern and central parts of the state, far from the southern region where these communities operate. This distinction is critical in understanding the realities of mining in Borno. While the state government justifies its 2023 ban by citing security concerns, there is little evidence that artisanal mining in Southern Borno funds terrorism.

For miners like Hassan, the ban has only deepened their struggles. “It will have a great impact on us, the poor,” he said. “If this is taken away from us, some may turn to crime.”

Buratai echoed this frustration. “Since the ban, we lack peace of mind. Security operatives patrol the sites, arresting miners. If you are unlucky, you end up in Biu or Maiduguri.” His fears are not unfounded—in March 2024, military troops attached to the 331 Battalion in Bayo arrested four suspected illegal miners and handed them over to the police.

With the industry now criminalised, miners like Hassan believe the government must either provide alternative jobs or allow them to continue mining under regulated conditions. “Nobody would risk his life and go into a pit if there were jobs,” he said. “Most of us here have families. If our source of survival is cut off, there will be a problem.”

The real threat appears to lie elsewhere—in the unchecked smuggling of minerals, corruption in enforcement, and the failure to regulate an industry that could provide legitimate economic opportunities. By conflating Borno’s mining economy with the terror-linked mines of Zamfara, policymakers risk punishing struggling miners rather than addressing the root causes of insecurity.

Who really profits from their toil?

The Borno State government’s ban on mining has not stopped the trade—it has merely driven it underground. Artisanal miners, desperate to make a living, have turned to smuggling networks that bypass official scrutiny, ensuring that minerals still flow from remote pits to international markets. These miners work in gruelling conditions, extracting minerals worth millions on the global market.

Yet, despite their backbreaking labour, they see only a fraction of the wealth their work generates. The real profits go to middlemen, dealers, and shadowy networks that control the illicit supply chain.

Miners told HumAngle that the minerals are smuggled out of Borno through Gombe, with networks expertly concealing them to evade detection. Once outside the state, they enter dealer hubs in Plateau, Kano, and Bauchi States, where they are processed and sold to international buyers from Sri Lanka, China, and Thailand.

“They would then export it by air or water. There are Chinese mining companies in Plateau State,” said Aliyu Abubakar, a 27-year-old miner in Chibra.

Idrisa in Gunda described the trade in even greater detail. “After buying from the miners here, we sell to major dealers in Jos, who in turn sell them to either the Sri Lankans, Chinese, or Thai, depending on the variety. Besides here in Gunda, we get this variety of sapphire in Garubula and Dadin Kowa under Biu and Ngulde in Askira-Uba.”

This covert trade indicates that Borno’s mineral wealth is enjoyed elsewhere. While miners endure hazardous conditions for meager wages, the real profits are made higher up the chain—by dealers who manipulate prices, security operatives who likely turn a blind eye, and foreign buyers who acquire Nigerian minerals at far below their global market value. The government, which imposed the mining ban under the guise of national security, has failed to address the glaring gaps that allow this illicit economy to thrive.

The Nigerian government has long struggled to regulate informal mining despite the sector’s economic significance. Instead of implementing structured policies to integrate small-scale miners into the formal economy, authorities have relied on outright bans—a tactic that often pushes mining operations further underground.

Among the most glaring failures in addressing the mining crisis is the mismanagement of the Ecological Fund, a federal initiative meant to mitigate environmental damage and support communities affected by mining, deforestation, and climate change.

In 2024, the 36 states in the federation received ₦39.6 billion ($26,4 million) from the Ecological Fund. Of this, Borno received ₦1.68 billion ($1.1 million)—an average of ₦140 million ($93,438) per month. It was the highest allocation in the entire Northeast and the second-highest in the country. Between 2021 and 2022, the state received over ₦2 billion ($1.33 million). This funding was designated for environmental restoration, reforestation, and support for communities impacted by mining-related degradation.

Yet, despite these substantial allocations, little evidence exists that the money has been used effectively. Reports indicate that while Borno received ₦816.34 million ($544,840) between Jan. and June 2024, only ₦20 million ($13,348) was utilised–for flood and erosion control. This lack of investment proved disastrous when, in September 2024, Maiduguri suffered one of its worst flooding crises, destroying homes, farmland, and livelihoods.

The state’s poor handling of Ecological Funds drew national scrutiny. The Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP) called on the federal government to investigate Borno’s spending of Ecological Funds from 2001 to June 2024.

In rural mining communities like Gunda, Chibra, and Dunkur, there is no sign of ecological interventions. Roads remain impassable, access to clean water is scarce, and deforestation continues unchecked.

Suleiman Toro, a community elder in Gunda, lamented the toll on agriculture. “Before, our lands were fertile. But after years of mining, the soil has become weak. The water sources are polluted, and farming has suffered. Yet, we have not seen any government projects to help restore the environment.”

As long as government neglect persists, the cycle of illegal mining, smuggling, and environmental destruction will continue—forcing communities to fend for themselves in a system designed to keep them on the margins.

Beyond the ban: a path to sustainable mining

The outright ban on artisanal mining in Borno has done little to curb illegal extraction or protect local communities. Instead, evidence suggests that it has pushed mining operations further underground, increasing risks for those involved while making the industry harder to regulate. This pattern is not unique to Nigeria—studies on artisanal mining regulations in sub-Saharan Africa indicate that blanket bans often drive miners into informal networks, where oversight is weaker and exploitation is rampant.

Experts and policymakers have long advocated for a more structured approach. Research by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) highlights the success of community-led mining cooperatives in countries like Zambia. These cooperatives formalise artisanal mining, ensuring safer working conditions, fair pricing, and legal recognition, benefiting the miners and the economy. Nigeria has explored a similar model—in 2013, the Federal Government registered 570 artisanal and small-scale mining cooperatives across the country as part of an effort to regulate the sector. However, implementation has been uneven, and many miners in Borno remain outside the legal framework.

A well-structured cooperative system in Borno could provide miners with protective equipment, training in safe extraction methods, and access to direct markets—reducing dependence on exploitative middlemen. By integrating artisanal miners into the legal economy, the government could not only improve safety and earnings but also generate revenue through taxation and licensing fees.

Furthermore, allocating a portion of mineral revenues to local development projects—such as reforestation programmes, water sanitation initiatives, and education—could help mitigate the damage caused by mining. The Ghanaian government has explored similar interventions, incorporating environmental restoration efforts into mining policies.

The real question is whether Nigeria’s government is willing to move beyond reactive bans and toward a structured, long-term solution—one that safeguards both the state’s mineral wealth and the livelihoods of its most vulnerable workers.

*Names with asterisks were changed to protect the sources.