Looks-wise, he had a humbleness that allowed him to play cops, working men and the president of the United States. The voice could grumble and soar, scraping the deepest recesses of evil and reaching the high-pitched cajoling of a championship schemer. Gene Hackman dodged and weaved. He bounced through early triumphs “Bonnie and Clyde” and “The French Connection” and was just getting started. As suggestive as his quiet performance is in Francis Ford Coppola’s Nixonian 1974 thriller “The Conversation,” all of Hackman’s turns have a complexity that made them endlessly fascinating. His killers told jokes; his heroes slouched. Upon the news of the actor’s death at age 95, we asked our staffers for their favorites; their answers ranged from high to low.

‘Young Frankenstein’ (1974)

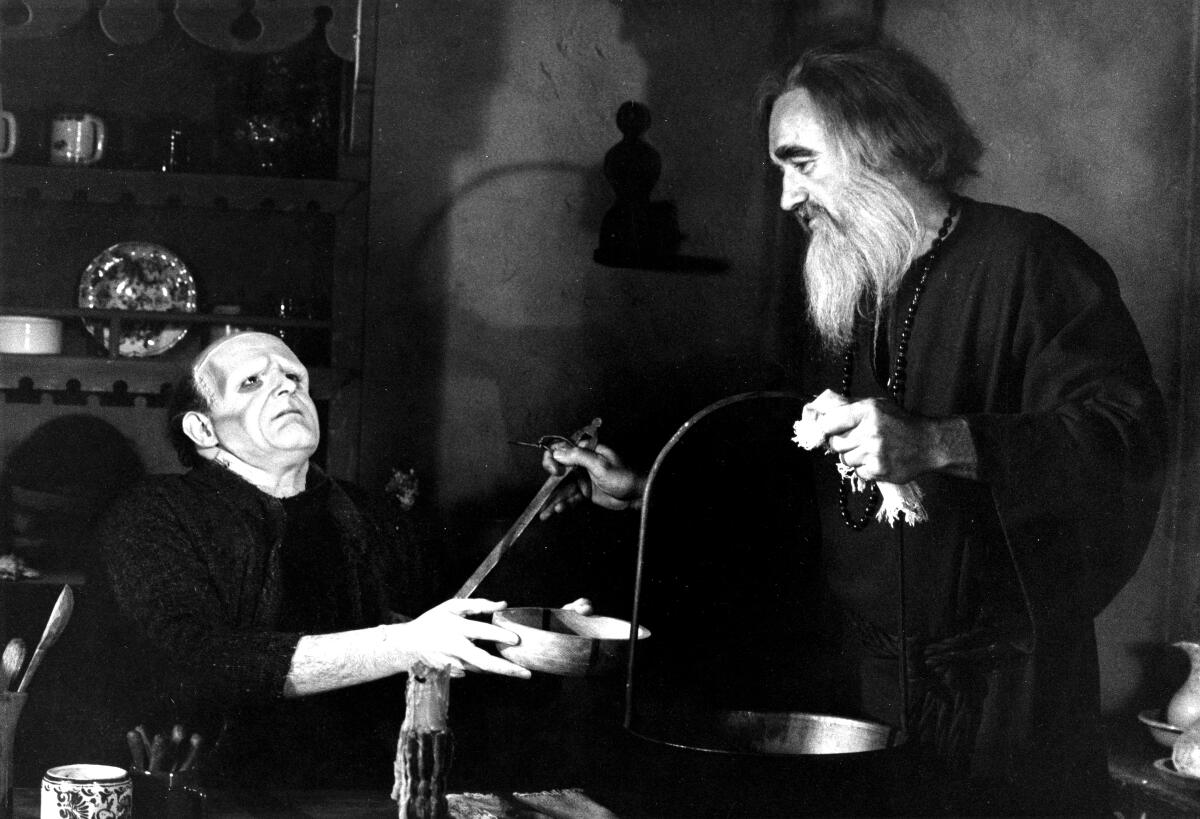

Peter Boyle, left, and Hackman in the movie “Young Frankenstein.”

(Hulton Archive / Getty Images)

“I know what it means to be cold and hungry,” Hackman stammers as his Harold the blind man ushers Peter Boyle’s monster into his shack. And he really did know. When Hackman resolved to act, he’d starved for years in an East Village walk-up with no hot water. He nearly lost a rare gig when the ingenue said he was too ugly.

We know that actors aren’t their characters. Still, you glimpse the real them in their choice of roles. Looking at Hackman’s résumé to understand how he saw himself, I’m drawn to 1974 when his success looked meteoric but he didn’t trust that Hollywood would welcome a leading man with a double chin.

Predicting the bubble would pop, Hackman said yes to too many violent roles. Then, at his busiest, with a wife and three children impatiently waiting at home, he wheedled Mel Brooks for a cameo in “Young Frankenstein.”

Brooks hadn’t offered the town’s hippest brute a part in his black-and-white spoof. Hackman’s tennis partner, Gene Wilder, told him about it.

“Is there anything in that crazy movie I could do?” Hackman asked. He’d glowered enough. Wilder told him about the small part of a blind man; Brooks told him there was no money in it.

“I just want to do it,” Hackman replied.

And I just want to watch this four-minute scene over and over again. The glassy stare, the eyebrows tilted up like thirsty caterpillars, his purr as he lights a cigar. Desperation roils off him like a lonely heart on a first date. Hackman improvised Howard’s famous last line: “I was going to make espresso.”

I shouldn’t read subtext into a cameo Hackman knocked out in two days. But it’s hard not to see the parallel between the generosity Howard heaps upon the overwhelmed stranger — hot spilled soup, shattered wine mugs, fists lit on fire — and the generosity Hollywood had thrust upon Hackman. He was fortunate to have been brought in from the cold. So why did he feel so scared?

It’s hard to know for sure when — or if — Hackman felt accepted as a movie star. There’s stretches where he stayed so hectic that I wonder if he was still insecure about his longevity, his typecasting, his face. What if Hollywood really looked at him and saw a freak?

“Young Frankenstein” is when Hackman got to come alive, when he realized he could control his image and his moves. Comedy let us know how much more he could do. And he could do it all. — Amy Nicholson

‘Night Moves’ (1975)

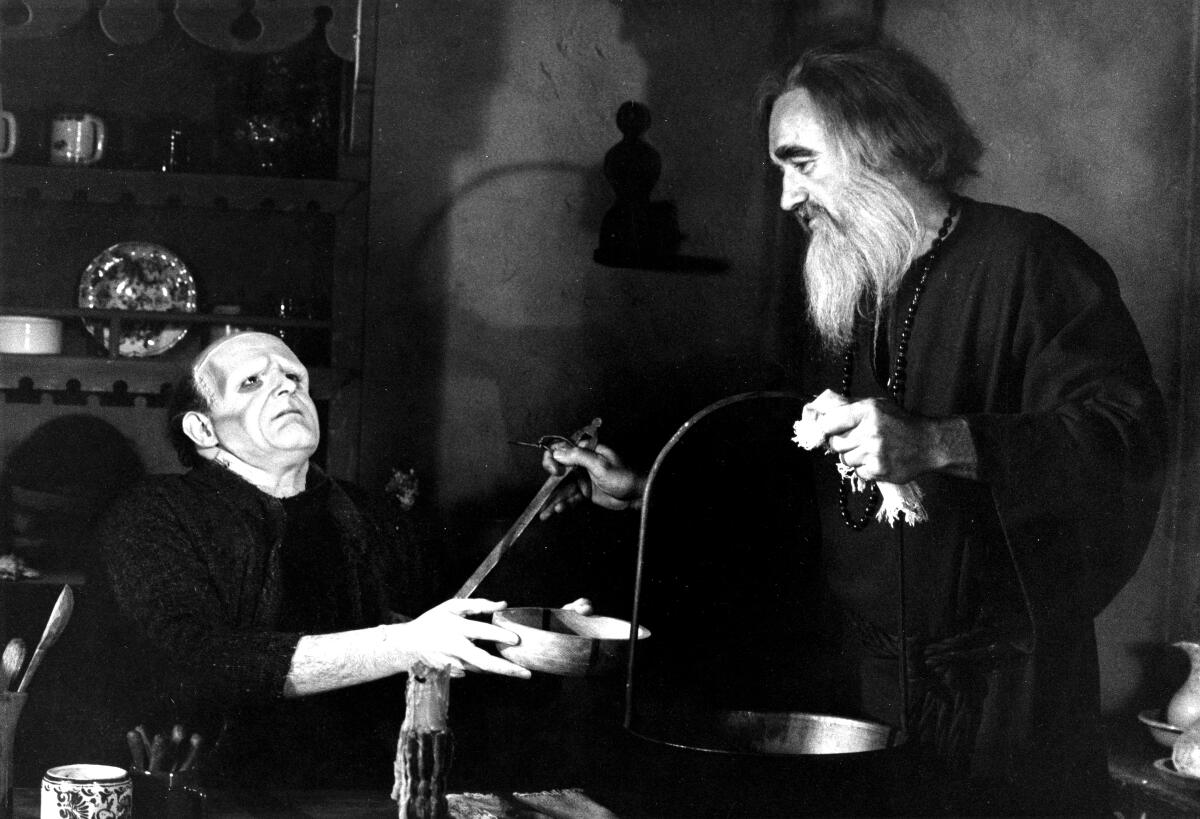

Hackman in the movie “Night Moves.”

(United Archives via Getty Images / FilmPublicityArchive)

Especially during his heroic run of work in the 1970s, Hackman was an astonishingly versatile actor, whether in the perverse satire of “Prime Cut,” the downtrodden naturalism of “Scarecrow” or countless other roles. Yet he also somehow always remained very much himself. Perhaps the greatest expression of the wounded, melancholy masculinity at the core of so much of Hackman’s work was in 1975’s “Night Moves.” (And that is to say nothing of the film’s fantastic wardrobe of tweeds, suede, slacks and turtlenecks that make for some enviable movie fits Hackman wears with a casual athletic grace.) In the film directed by Arthur Penn, who had previously worked with the actor on his breakthrough role in “Bonnie and Clyde,” Hackman plays Harry Moseby, a former pro football player turned L.A. private detective. He is hired by a faded actress to retrieve her wayward daughter, a job that takes him to the Florida Keys. Moseby doesn’t enter the story with any sort of idealism and yet he is still unmoored by just how cynical, sordid and despicable the world he is drawn into turns out to be. At one point, as Moseby is desperate to avoid confronting his wife over her infidelity, he glumly watches a ballgame on TV. Hackman wrings an entire shaken worldview from his response when she simply asks who’s winning. “Nobody,” he says. “One side’s just losing slower than the other.” — Mark Olsen

‘Superman’ (1978)

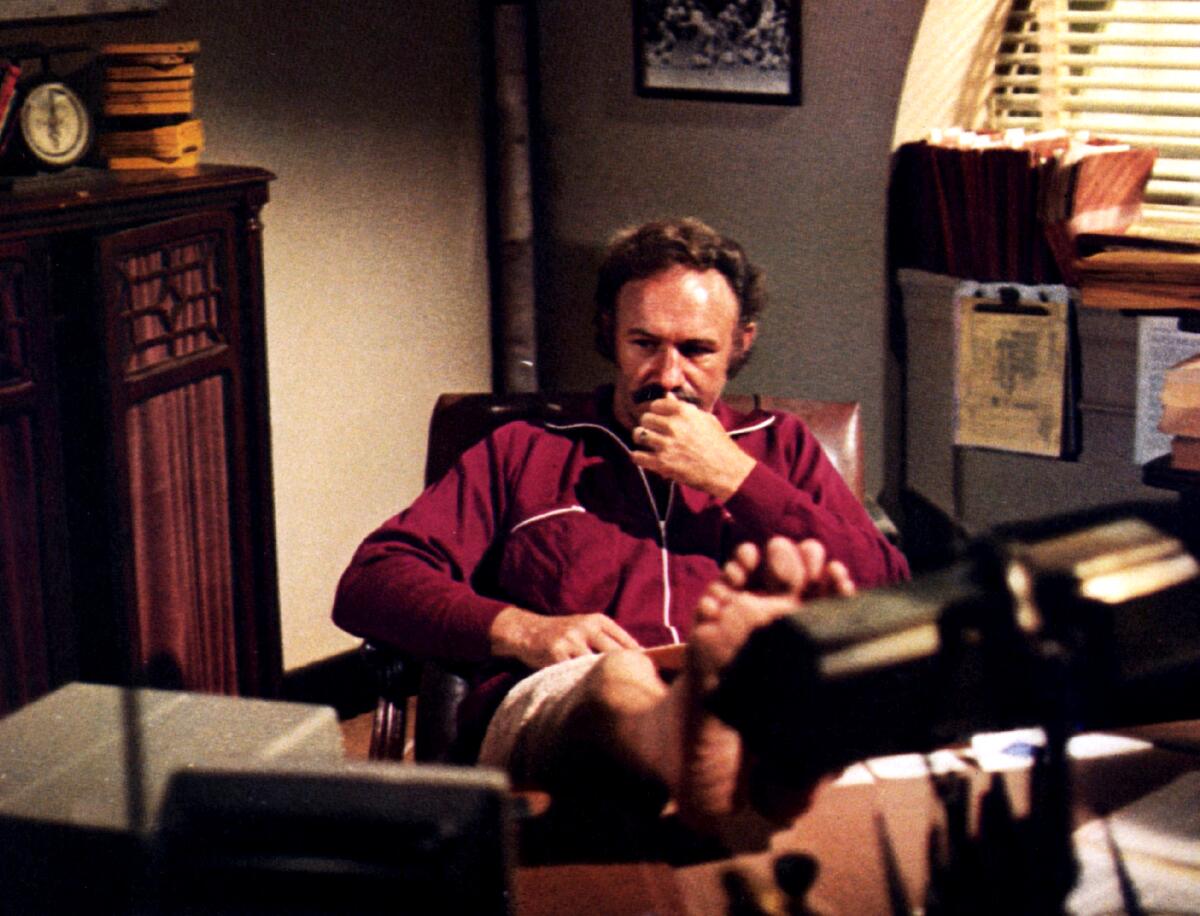

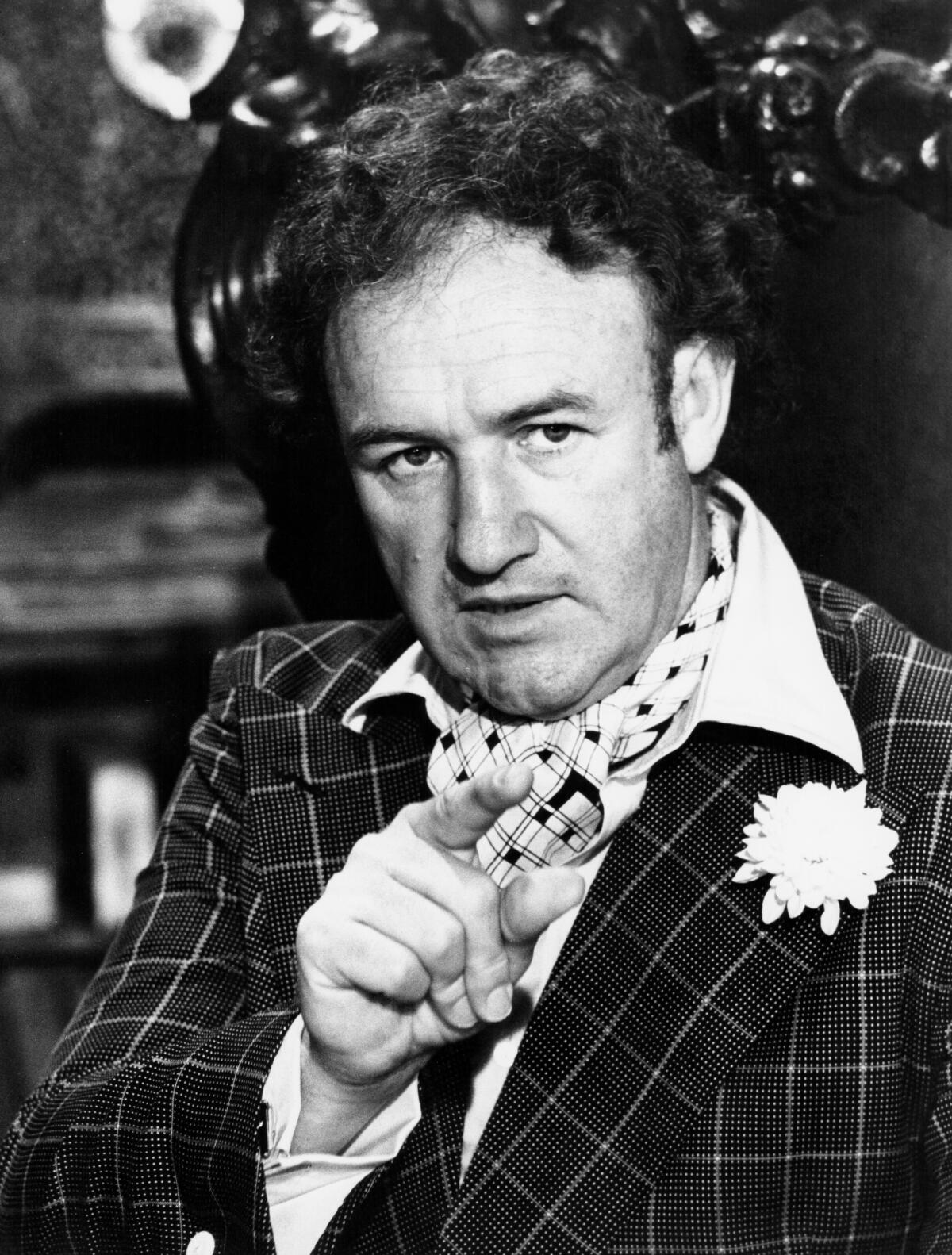

Gene Hackman as Lex Luthor in the movie “Superman.”

(Stanley Bielecki Movie Collection / Getty Images)

At the tender age of 6, long before I saw Hackman in his more serious, nuanced roles, his iconic turn as Lex Luthor in Richard Donner’s “Superman” hit me like a superpowered punch. With his goofy, slightly pathetic wig and gleeful malevolence, Hackman’s Luthor was as absurd as he was menacing — a villain you couldn’t help but root for, even as he plotted to destroy California by triggering the San Andreas Fault with a missile detonation. Compared to the grim interpretations of later Lexes, like Jesse Eisenberg’s twitchy, unhinged take or Kevin Spacey’s cold, corporate villain, Hackman’s Luthor was more like a campy Bond villain, ridiculous, vain and irresistibly funny, reveling in his schemes with theatrical flair. With Ned Beatty serving as the perfect comic foil as his bumbling henchman Otis, Hackman’s playful brand of evil mastermindery would go on to set the template for future comic-book antagonists, from Jack Nicholson’s Joker to Tom Hiddleston’s Loki. As Hackman later said of the role, “It’s like a license to steal. Almost anything you do is going to be OK because he’s kind of flamboyant and deranged and all the things actors love to play. I wouldn’t play Superman for anything.” — Josh Rottenberg

‘Mississippi Burning’ (1988)

Hackman, left, and Willem Dafoe in the movie “Mississippi Burning.”

(David Appleby / Orion Pictures Corp.)

“Mississippi Burning” was, for me, the ultimate Gene Hackman film. Not just because its story — the 1964 investigations into the murders of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner — remains horrifically powerful and still (alas) resonant, but because Hackman’s role personifies just what made him one of the few leading men who remained unquestionably a character actor. Director Alan Parker’s 1988 film captures a time when many small Southern towns were tightly gripped by the violent racism of the KKK. After three civil rights workers go missing, two FBI agents are sent to investigate: Alan Ward (Willem Dafoe), a young, uptight Northerner who wears his anger on his sleeve, and Rupert Anderson (Hackman), a former Mississippi sheriff who understands that there is nothing to be gained, and much to be lost, by a full-frontal attack. Anderson’s ability to use neighborly charm to gain access and trust mirrors Hackman’s own talent for creating characters who, good or evil, were always deeply human — no matter the role, we followed him because we recognized him. The scene in which Anderson single-handedly faces down both the corrupt deputy and the Klan’s most murderous henchman is a master class in range. Hackman enters with a genial familiarity only to make it very clear that the Klan will underestimate him at its peril. In less than three minutes, we are reminded that the same was always true of Hackman himself. — Mary McNamara

‘Unforgiven’ (1992)

Hackman, left, and Clint Eastwood in the movie “Unforgiven.”

(Warner Bros.)

David Webb Peoples wrote a legendary script in the late 1970s, a time when westerns could have running gags, cynical wisdom and big-time reversals of fortune. Right at its center is a two-scene knockout about the making (and unmaking) of reputations that only an actor of Hackman’s deftness could pull off. Both scenes take place in a jail; they’re built out of the same kind of conversational fireworks that Howard Hawks used to make “Rio Bravo.” In the first, Hackman’s local sheriff, Little Bill Daggett, already cemented in our brains as vicious, reveals himself to be a shrewd mocker of the written word as well. The “Duck of Death,” he insists on calling his prisoner, English Bob (Richard Harris), and it takes him only a couple of times before you realize he’s not mispronouncing the word duke. (A fawning biographer watches his book get torn to shreds in real time.) By the next scene, we see that Little Bill has grabbed the spotlight for himself, ballooning into a gasbag of self-importance. But watch those eyes widen when suddenly there’s a test of guts and his meanness flares again. Only Hackman could shift like that, from raconteur to angel of death. He lives rent-free in my head for these minutes of screen time alone. — Joshua Rothkopf

‘The Firm’ (1993)

Hackman, left, and Tom Cruise in the movie “The Firm.”

(Francois Duhamel / Sygma via Getty Images)

He was my earliest memory of the reluctant villain, the character who is both decent and corrupt. And it was mesmerizing to watch. As Avery Tolar, the senior partner at a Memphis law firm deeply entrenched in the criminal enterprises of a Chicago mob family, Hackman brought depth in the shades of a tortured man in too deep. A young Tom Cruise may have been the star of Sydney Pollack’s adaption of the John Grisham novel about a fresh-out-of-college associate, Mitch, whose money-focused ambition allows him to get bamboozled into joining the firm’s ranks. But Hackman’s Avery was the more intriguing character as the guy, his own fate already set, who is tasked with leading Mitch on the crooked path. He’s older and wears the years of corruption in a stretched smile that could be both disarming and uncomfortable, masking a conscience that’s been buried but still within reach. The scene that came to mind upon learning of Hackman’s death was the moment near the end of the film when Avery, thinking of a life taken from him by his sins for the firm, is alone with Mitch’s wife, Abby (Jeanne Tripplehorn), in her attempt to distract him so she can secure evidence to bring down the firm. The henchmen are onto her, but Avery gives her the out she needs to get away. “What are they going to do to you?” she asks. “Whatever it is, they did it a long time ago,” he replies. It’s a brutal truth that Hackman delivers with subtle yet painful intensity. It opened my eyes to how complicated humanity can be. — Yvonne Villarreal

‘The Royal Tenenbaums’ (2001)

Ben Stiller, left, Jonah Meyerson, Grant Rosenmeyer, Gwyneth Paltrow and Hackman in the movie “The Royal Tenenbaums.”

( James Hamilton / Touchstone Pictures)

I have watched Wes Anderson’s “The Royal Tenenbaums” countless times over the years, and the ending of that movie never fails to get me. And that’s all Gene Hackman. Playing Royal, the family’s deeply flawed patriarch, Hackman makes this man — a father who abandoned his family and, even when he was around, acted like a jackass — into a charming rascal whom you root for as he attempts to make up for lost time and past sins. “Can’t somebody be a s— their whole life and try to repair the damage?” Royal asks. At first, it’s all an act. Literally. He says he’s dying from stomach cancer. Of course, he’s soon discovered to be lying. (His daily three-cheeseburger diet is a tipoff.) As he slinks off, Royal says that the past six days have been the best of his life. And he’s surprised because he means it. You see that astonishment on Hackman’s face, which sells Royal’s redemption and makes the movie’s tender denouement work. Hackman didn’t want to make “The Royal Tenenbaums.” It was a lot of work, the pay was scale and Anderson wasn’t yet a brand-name director. Thankfully, Hackman’s agent sold him on doing it. So many scenes from this legend’s career are indelibly etched in my mind. But none brings me more joy than watching Royal and his two grandsons go-karting through the streets of New York to the sounds of Paul Simon’s “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard.” I’m smiling now just thinking about it. — Glenn Whipp