6 best desert books to read: Essential Southwest literature

Reading List

Reading List

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The word “desert” suggests barrenness for many, but anyone who lives in or near one knows how rich, wild and complex it can be. That’s equally true of the best books set there. The winter months are the best time to travel to the desert — but tucking into one of these titles is timeless, of course. Here is a brief selection of some of the best desert reads, old and new, that put the Southwest at their center. Whether you’re planning a road trip or reading from the comfort of home, get a glimpse of awe-inspiring vistas, rugged wildlife, tales of resilience and more.

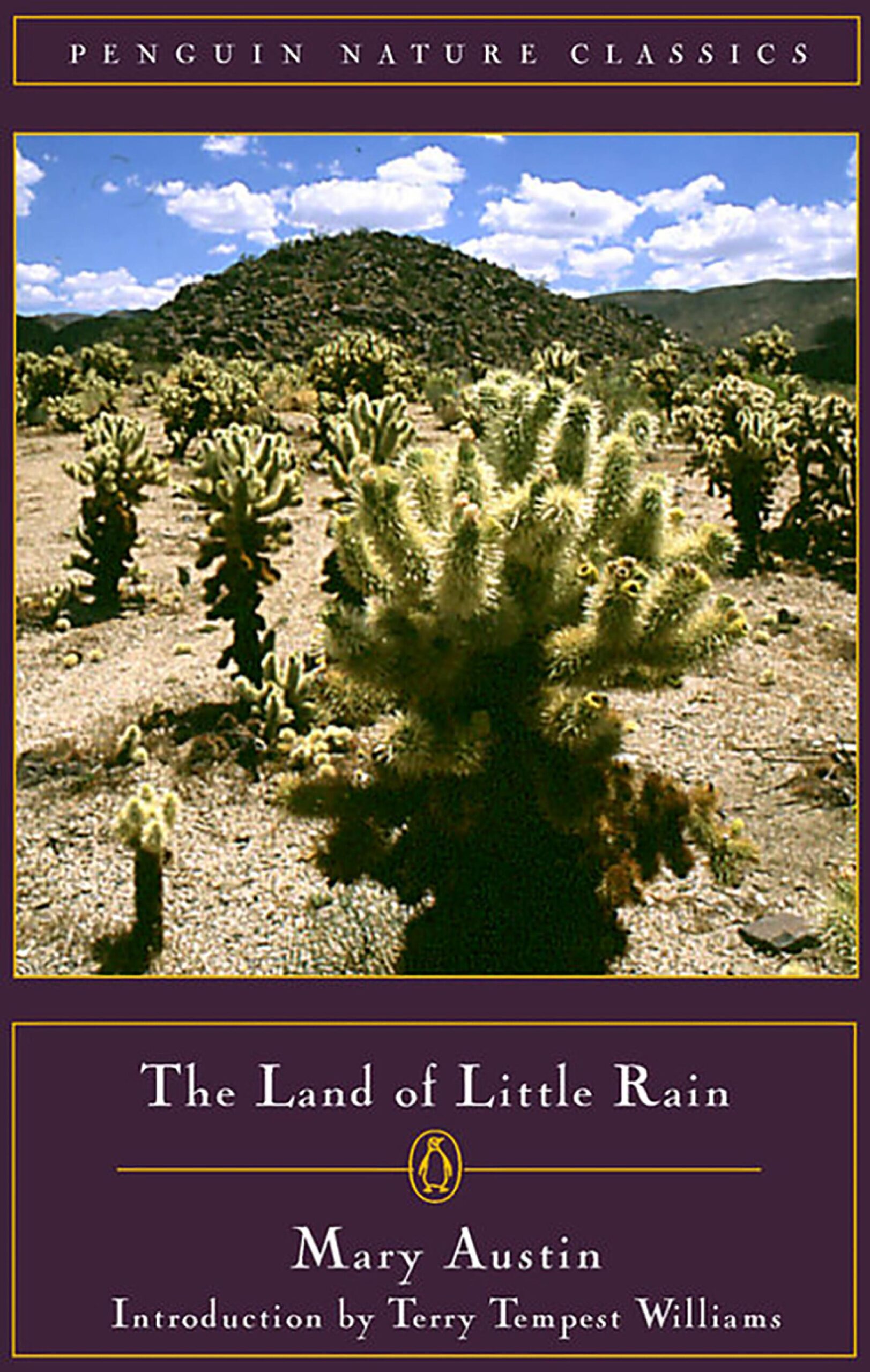

“The Land of Little Rain”

By Mary Austin

Penguin Classics: 128 pp., $17

(1903; reprint 1997)

Arguably the first collection of lyrical essay writing about the California desert, Austin drew on her travels through the Owens Valley and environs, covering mining, the Shoshone tribe, weather and water. The book is thrilling in Austin’s close attention to details, from the grasses to rivers and hard-trod trails. Here, she writes, “it is possible to live with great zest, to have red blood and delicate joys.”

“Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness”

By Edward Abbey

Ballantine Books: 352 pp., $10

(1968; reprinted 1985)

Chronicling his stint in Utah’s Arches National Park in the late ‘50s, Abbey’s bestselling memoir revealed the beauty and fragility of the Southwest to a wider American audience, depicting the punishing weather and awe-inspiring vistas while thundering against the masses of lookie-loos driving into the desert only to despoil it. It’s often likened to “Walden,” but Abbey’s flinty, darkly humorous voice gave Western literature a tone distinct from East Coast gentility and folksy cowboy writing.

“Desert Oracle, Volume 1: Strange True Tales from the American Southwest”

By Ken Layne

Picador: 304 pp., $20

(2021)

Part handbook, part folklore collection, part tribute to the Southwest, Layne’s entertaining chronicle is built on brief chapters about the outlaws, writers, singers and other characters who define the region’s hardy reputation, from the path of Western swing musicians from Texas to L.A. to UFO conspiracists who convene in New Mexico, the Manson family’s trek to Death Valley, and beyond.

“The Deserts of California: A California Field Atlas”

By Obi Kaufmann

Heyday, 576 pp., $55

(2023)

Kaufmann’s lavishly illustrated field guide to the state’s arid regions is wide-ranging both geographically (from the Great Basin to the north and the Sonoran and Mojave to the south) and in terms of the species covered, from bats to bobcats and chias to palo verdes. It’s built for both the backpack and end table, with detailed descriptions alongside pleas for the land’s preservation.

“Mecca”

By Susan Straight

V: 384, $19

(2022)

A contemporary epic set in the Imperial Valley, Straight’s novel is a cross-section of desert denizens — a motorcycle officer, a Palm Springs spa employee, a family rocked by a police shooting — set against the demands of desert life. Encompassing COVID-19 and wildfires, it speaks to the present while exploring the region’s long history.

“Mojave Ghost”

By Forrest Gander

New Directions, 80 pp., $16

(2024)

“In this xeric topography / we fold ourselves into the circumstance of desert foothills / chewed away by leprosies, toothed winds, and / sudden rains,” writes the Pulitzer-winning poet Forrest Gander in this book-length poem about his hike across the 800 miles of the San Andreas Fault after the deaths of his wife, poet C.D. Wright, and mother. Though the writing is informed by the starkness of the landscape, he writes beautifully about the desert’s healing powers.

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”