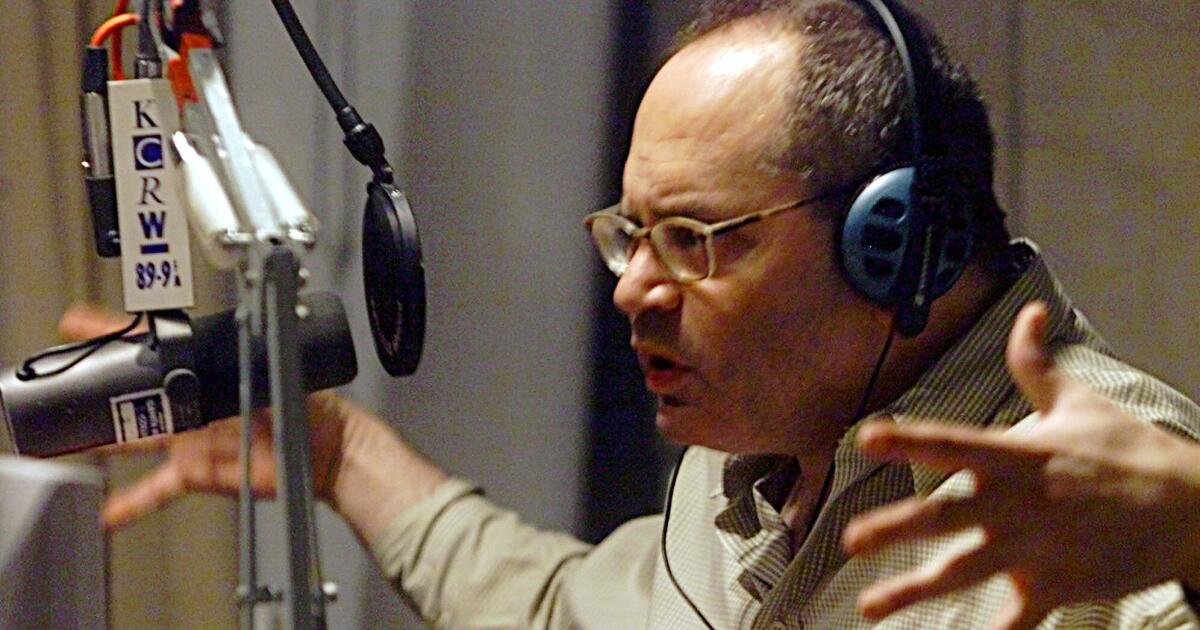

Michael Silverblatt dead: ‘Genius’ host of KCRW’s ‘Bookworm’ was 73

Michael Silverblatt, the longtime host of the KCRW radio show “Bookworm” — known for interviews of authors so in depth that they sometimes left his subjects astounded at his breadth of knowledge of their work — has died. He was 73.

Silverblatt died Saturday at home after a protracted illness, a close friend confirmed.

Although Silverblatt’s 30-minute show, which ran from 1989 to 2022 and was nationally syndicated, included interviews with celebrated authors including Gore Vidal, Kazuo Ishiguro, David Foster Wallace, Susan Orlean, Joan Didion and Zadie Smith, the real star of the show was the host himself, the nasal-voiced radio personality who more than once in life was told he did not have a voice for his medium.

His show represents one of the most significant archives of conversations with major literary powerhouses from the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

But Silverblatt knew that he was as much a character as the people he interviewed.

“I’m as fantastical a creature as anything in Oz or in Wonderland,” he said during a talk in front of the Cornell University English department in 2010. “I like it if people can say, ‘I never met anyone like him,’ and by that they should mean that it wasn’t an unpleasant experience.”

Born in 1952, the Brooklyn native learned to love reading as a child when he was introduced to “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.” Neighbors would see him walking the streets of Brooklyn with his head in a book and would sometimes call his parents out of fear he might get hurt.

But until he left home for the University at Buffalo, State University of New York, at the age of 16, Silverblatt has said, he had never met an author.

His college, however, was filled with such famous authors as Michel Foucault, John Barth, Donald Barthelme and J.M. Coetzee, who were all working as professors.

Silverblatt was shy and too embarrassed to speak during class because of his inability to clearly pronounce the letter “L,” which appears three times in his own name. Yet he considered the authors to be his friends, even if they did not know it yet, he said during the Cornell talk.

He would approach them after class to speak about their work.

Despite his interest in literature, Silverblatt’s parents wanted him to become a mail carrier, he said. The summer after his freshman year, Silverblatt worked a New York City mail route, delivering letters to the mayor’s mansion on an Upper East Side route that took him past numerous old bookstores and used-books shops. During that job, he said in the Cornell talk, he purchased the complete works of Charles Dickens.

Silverblatt moved to Los Angeles after college in the mid-1970s and worked in Hollywood in public relations and script development.

Like many young writers in Los Angeles, he wrote a script that never got made.

It was in Los Angeles that Silverblatt met Ruth Seymour, the longtime head of KCRW.

Seymour had just returned to the United States from Russia and was at a dinner party where everyone was discussing Hollywood. There, she and Silverblatt became immersed in a one-on-one discussion of Russian poetry.

“He’s a great raconteur and so the rest of the world just vanished,” Seymour told Times columnist Lynell George in 1997. “Afterward I just turned and asked him: ‘Have you ever thought about doing radio?’”

For the next 33 years, that’s exactly what he thought about.

“Michael was a genius. He could be mesmerizing and always, always, always brilliant,” said Alan Howard, who edited “Bookworm” for 31 years.

“It’s an extraordinary archive that exists, and I don’t think anyone else has ever created such an archive of intelligent, interesting people being asked about their work,” Howard said. “Michael was very proud of the show. He devoted his life to the show.”

Silverblatt once dreamed of being on the other side of the microphone, as a writer in his own right, Howard said. But he faced bouts of writer’s block through his 20s and gave up writing.

“Eventually, he came to find peace with the reality of that,” Howard said.

Instead of writing, he became an accumulator of a vast amount of other writers’ work — in his library as well as the repository in his head. He had an incredible memory for the books he read.

Silverblatt converted the apartment next to his Fairfax apartment into a library where he kept thousands of books, Howard said.

“It was heaven,” he said. “It was a fabulous library.”

“He was such a singular person,” said Jennifer Ferro, now the president of KCRW. “He had a voice you would never expect would be on radio.”

Alan Felsenthal, a poet who considered Silverblatt a mentor, called Silverblatt’s voice “sensitive and tender.”

Felsenthal said the show was about creating a space of “infinite compassion,” where writers could share things they might not share in everyday conversation.

“Michael was one of a kind, truly singular. And his voice is too,” Felsenthal said.

One of the most important tenets of Silverblatt’s approach was that he not only read the book he was discussing on his show that day, but also read the entire oeuvre of the authors he interviewed.

“A significant writer would come in and be bowled over by Michael’s depth of vision of the work at hand,” Howard said.

David Foster Wallace, in one interview, said he wanted Silverblatt to adopt him.

Silverblatt said he strove to read an author’s entire body of work, but he never claimed to have read it all if he hadn’t.

“In general I try to read the author’s complete work. … That’s not always true, and I never say it if it isn’t true. But more often than not, I have, at least, read the majority of the work. And sometimes it’s a superhuman challenge,” he said in the 1997 Times column.

The voracious reader said that the best books, those that brought him happiness, were not the ones that ease our way in this strange and difficult world.

“The books I love the most made it harder for me to live,” he said.

Silverblatt is survived by his sister, Joan Bykofsky.