Tourism, Power, and Dependency: The Case for a Mercantilist Gambia

Tourism has been said to be The Gambia lifeline. The Smiling Coast has been receiving thousands of visitors who come to the region due to its warm reception and lively culture. Tourism has been touted as one of the greatest success stories in the country with almost a fifth of the national GDP and with thousands of employees in the formal and informal sectors. But it is a silent fact, seldom admitted, that beneath the smiling faces and the colorful postcards there is a lot more to be lost than gained by the Gambia in its tourism business. Tourism appears as a treasure of the state, however, to a great extent it turned out to be a trap in the economy.

The Gambia imported into its own country has followed an economic paradigm of liberalism, despite the fact that it idealizes open markets, deregulation, and foreign investment as the fastest way to development. The premise was straightforward, with opening up the tourism industry to foreigners, the nation would acquire employment, expertise, competition and eventually general prosperity. The tourism situation in Gambia today however tells a different story. It is not romantic, empowering or lucrative as many make it out to be. Interdependence has not brought about mutual prosperity; it has brought dependence.

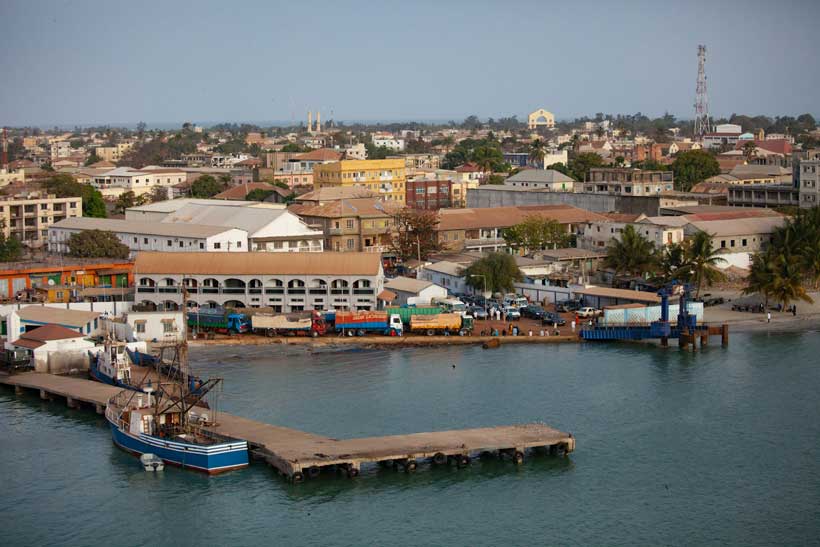

A report released by UNCTAD (2022), the Gambia is losing up to 70 percent of its tourism income to foreign owned hotels, offshore booking systems, imported goods, airlines and repatriation of earnings. Most of the payments that are made by many tourists are made in Europe prior to getting on the plane. The government of Gambians has lost most of the potential earnings by the time they find themselves in Banjul.

This trend in the economy is not solely possible. It is indicative of a world dynamic as such as defined by dependency theorist Andre Gunder Frank (1966) who opined that developing countries tend to provide labour, culture, and even resources, as wealth and power is drained to more dominant players in the global arena.

Control of tourism in Gambia by the foreigners is not merely a matter of cash but a question of power. Major tour operators, international booking networks and foreign hotel chains are often in charge of the decisions of marketing, pricing, target groups and national branding. The industry involves local stakeholders, such as guesthouse owners, tour guides, craft sellers, musicians, farmers, taxi drivers, etc., who are not architects of the industry.

According to Robert Gilpin, a political economist (1987) cautioned that the global marketplace does not operate in terms of morality and fairness but on the basis of power, interests and strategic advantage. The adoption of liberal optimism in Gambia presupposed that the openness would bring about prosperity by default. But openness lacks strategy, and interdependence has no bargaining power; it is easy to exploit such weaklings. Well-intended policies without strategic protection are now yielding their results on the Gambia.

This does not imply that The Gambia should isolate and give up tourism. Tourism is one of the most feasible pillars of development of the country with limited natural resources, small domestic market, small industrial capacity and its geographical location. The problem of the model is not its structure, but its structure. The problem is not the existence of the foreigners but the lack of Gambians in the core of the industry. The issue is with ownership and control, unequal distribution of ownership, control and value.

Here the contemporary mercantilistic approach applies. Global engagement is not rejected in mercantilism but there must be strategic engagement. It does not see national wealth as the by-product of open markets, but a resource that has to be maintained and nurtured. A state that is mercantilist does not just watch over markets, it controls them. This is not to shut the borders but to make sure that national interests take precedence, relationships have to be founded on equal footing and economy has to feed its own citizens before it feeds others.

According to Peter Evans (1995), a political economist, refers to this as embedded autonomy a model, in which the state is strong, capable and visionary, but is also tightly related to society and local industries.

Three strategic pillars on which a mercantilist turn in Gambian tourism must be based are:

The ownership of the Gambians should be central and not peripheral.

The government assistance should be in form of available financing, taxation reforms, tourism incubators, land protection policies, investment literacy and procurement reforms which will favor Gambian owned hotels, lodges, transport organizations, tour agencies and tourism academies. No country can establish long term prosperity based on leased platforms.

Tourism has to be associated with agriculture, manufacturing, and creative industries.

Importation of food, drinks, furniture, art, souvenirs, and building materials has been a significant missed opportunity to most tourist hotels. The hospitality industry should be provided by Gambian farmers, carpenters, craft makers, tailors, artists, and designers. Once tourism sustains other industries, the money circulates and multiplies and is retained in the country.

The Gambia has to regain its tourism identity and branding.

It is now being promoted as a cheap winter resort to the rest of the world instead of a cultural giant. The Gambian culture, heritage, and values should become the driving force of the new tourism narrative, developed by Gambians themselves.

Critics tend to believe that The Gambia is too small to make bargaining power. However, size is not as important as strategy in international politics. Through ECOWAS and the African Union, small states are able to form regional blocs and speak with one voice.

The current trends in the world are not towards economic liberalism blindly. Even countries that were once the proponents of open markets are currently reshoring their industries, subsidizing, and empowering national value chains.