The old walls of St. Francis Xavier Catholic Church in Owo, Ondo State, South West Nigeria, shook at 9:30 a.m. on June 5, 2022. It was Pentecost Sunday, and the priest’s burning of incense hung in the air. The choir was mid-hymn when the first explosion fractured the rhythm.

Eyewitnesses recalled two men stationed by the doors, firing automatic rifles into the congregation. When the smoke cleared, over 40 worshippers lay dead — children, ushers, and the parish catechist among them. HumAngle spoke to families of the victims, including Akinyemi Emmanuel, whose wife was killed, and Christopher, whose older brother was also a casualty.

The massacre made global headlines, but beyond the horror lay a familiar pattern — the tactics, the timing, and the grim echoes of earlier carnage: Madalla’s St. Theresa’s Church (2011), Kano’s Central Mosque (2014), Kaduna’s Murtala Square (2014), and Mubi’s Madina Mosque (2017).

The data of devastation

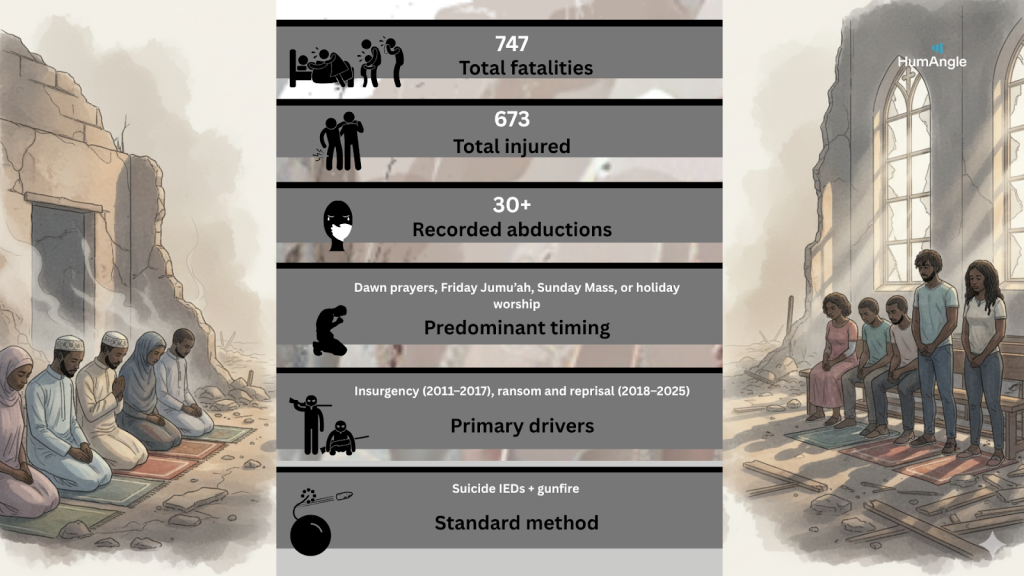

HumAngle’s field researchers verified 20 major attacks on places of worship across Nigeria between 2011 and 2025. Each incident was cross-checked against ACLED, CFR’s Nigeria Security Tracker, official statements, and humanitarian field reports.

“Every line of data is a broken family,” said a researcher who assisted in the compilation. “We tracked events, but what we found was grief mapped onto geography.”

Key Figures

From 2011 to 2015, churches bore the brunt — Boko Haram’s campaign against the state and society, often weaponising sectarian imagery. Between 2016 and 2021, mosques and Islamic gatherings became targets as extremists purged dissenting clerics. By 2022, the pattern shifted again — terrorists and militias attacked worshippers of both faiths for ransom or reprisal.

Early years of fire (2000–2010): Shari’a, riots, and mob rule

The roots of Nigeria’s religious bloodshed date back to pre-independence; however, this report will examine only the events from 2000 to 2025. In the year 2000 when 12 northern states reintroduced Shari’a law. What began as a demand for moral order soon morphed into violent attacks against non-Muslims.

By 2001, the tension had already turned deadly. Over 100 people were killed in Kano, according to The Guardian (UK), after riotous Muslim youths attacked the minority Christian population in the city. Human Rights Watch later documented the carnage of reprisal that took place in Jos, with similar riots in Kaduna.

Shari’a’s reintroduction became both symbol and signal — a moral protest against state failure but also a green light for mob justice.

The spiral continued. In 2002, Kaduna was a flashpoint again. The infamous Miss World Contest riots, triggered by a controversial ThisDay article deemed blasphemous against Islam. The riots left at least 200 dead.

As the years passed, intolerance became routine. In 2006, a Bauchi-based teacher, Florence Chukwu, was lynched for allegedly confiscating a Qur’an from a student. A year later in Gombe, another teacher, Christiana Oluwasesin, met the same fate. Then, in 2007, Kano’s Tudun Wada suburb witnessed the killing of dozens of Christians after a student was accused of alleged blasphemy.

Two decades later, the script remained tragically familiar. In May 2022, a Christian student, Deborah Samuel Yakubu, at Shehu Shagari College of Education, Sokoto State (a Muslim-majority state), was accused of blasphemy, then stoned, beaten and set on fire by a mob of Muslim students.

Even Muslims have not been spared from mob attacks due to alleged blasphemy against Islam. In 2008, a 50-year-old man was beaten to death in Kano, while Ahmad Usman, a Muslim vigilante, was burnt alive in Abuja in 2022.

In 2023, Usman Buda, a butcher in Sokoto, was stoned to death by his peers. In 2025, food vendor Ammaye met a similar fate in Niger State after an argument over religious differences.

From Pandogari to Sokoto, Facebook posts, WhatsApp messages, and street rumours have become digital triggers for extra-judicial deaths.

Nigeria’s decade of supposedly holy violence took a new form with Boko Haram’s rise. The insurgency’s ideological war turned places of worship into battlefields as they circulated videos of beheading of Christians and the Muslims they accused of spying for the Nigerian state.

The Madalla Christmas massacre — 2011

On Christmas morning, a suicide bomber detonated a car outside St. Theresa’s Catholic Church in Madalla, Niger State, killing at least 40. Boko Haram claimed responsibility, vowing more attacks against Christians “for government sins”.

Attack on COCIN Headquarters in Jos — Feb 2012

A year later, a suicide bomber drove an explosives-laden vehicle into the Church of Christ in Nations (COCIN) headquarters in Jos during Sunday service, killing at least three worshippers and injuring dozens. The blast destroyed parts of the church and nearby buildings.

Suicide Bomb Attack at St Finbar’s Jos — March 2012

Barely a month after the attack, a car bomber targeted St. Finbar’s Church in the Rayfield area of Jos during Mass. The explosion killed 14 people and wounded over 20, causing extensive damage to the church premises.

Silencing the critics — 2011–2014

In Biu, Borno State, Shaykh Ibrahim Burkui was assassinated in June 2011 for criticising Boko Haram. His death, along with that of Ibrahim Gomari in Maiduguri and Shaykh Albani Zaria in 2014, underscored the extension of the group’s wrath to Muslims who opposed its doctrine.

Kano Central Mosque bloodbath — 2014

On Nov. 28, 2014, twin suicide blasts struck Kano’s Central Mosque. As worshippers fled, gunmen opened fire. About 80 died. Boko Haram attacked Sunni Muslims loyal to the Emir of Kano, Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, who had condemned extremism.

Eid of Ashes — Damaturu 2015

A 10-year-old girl walked into an Eid prayer ground in Yobe and detonated explosives, killing 50. A morning of celebration turned into a funeral for hundreds of people.

Mutations of terror (2016–2021)

AAfter the insurgency’s initial high tide receded, violence splintered into ideological and economic strands.

- 2016 (Molai-Umarari, Borno): Two female suicide bombers killed 24 during dawn prayers.

- 2017 (Mubi, Adamawa): A teenage bomber killed 50 in a mosque.

- 2017 (Ozubulu, Anambra): Gunmen killed 12 during a Mass — incident later linked to a local feud.

- 2018 (Mubi, Adamawa): 86 worshippers were killed after two suicide bombers detonated explosives in a mosque during an afternoon prayer.

- 2021 (Mazakuka, Niger): Terrorists killed at least 18 worshippers at a local mosque during Fajr prayers.

- 2021 (Yasore, Katsina): 10 killed in evening prayers.

- 2021 (Okene, Kogi): Three people were abducted from a Living Faith Church during a prayer meeting. They were later released.

- 2021 (Fadan Kagoma, Kaduna): Terrorists attacked and kidnapped three seminarians at Christ the King Major Seminary. Michael Nnadi, one of the captives, was later killed, while the others were released.

“The violence metastasised,” said Olawale Ayeni, an analyst in Abuja. “What began as jihadist warfare became an economy of fear — raids, ransoms, and retaliations.”

The new normal (2022–2025): Terrorism meets belief

Owo, Ondo State — June 2022

On Pentecost Sunday, attackers detonated explosives and opened fire at St. Francis Xavier Church, killing 41 and injuring 70. Initially attributed to ISWAP, investigations revealed financial links to northwestern terrorist networks.

Kafin Koro, Niger State — January 2023

Isaac Achi, a Catholic priest, was burnt to death in the early hours of the morning at the presbytery of Sts. Peter and Paul Catholic Church, Kafin Koro, in Niger State. The residence was also reduced to ashes. Achi was the parish priest in charge of St. Theresa’s Catholic Church, Madalla, when it was attacked in 2011.

Kajuru, Kaduna State – September 2024

Gunmen invaded two churches in Bakinpah-Maro during service, killing three and abducting several others. Videos later surfaced showing captives reciting prayers under duress.

Bushe, Sokoto – February 2025

Terrorists invaded a mosque in Bushe Community of Sabon Birni LGA, Sokoro State. They kidnapped the Imam and 10 other worshippers during the dawn prayer.

Marnona Mosque Attack, Sokoto – August 2025

On Sunday, Aug. 12, terrorists stormed a mosque in Marnona village in Wurno LGA of Sokoto State, killing one worshipper and abducting several others.

Unguwan Mantau, Katsina — August 2025

During early morning prayers, terrorists opened fire inside a mosque, killing 27. Survivors said the attackers accused locals of tipping off soldiers.

Gidan Turbe, Zamfara State – September 2025

Terrorists stormed a mosque in Gidan Turbe of Tsafe LGA, Zamfara State, and abducted 40 worshippers during a dawn prayer. Reports indicated that the attack happened barely 24 hours after a peace deal with the gunmen terrorising the village.

In recent years, the distinction between ideology and economics has become increasingly blurred. Many southerners who are predominantly Christians living in the north are business owners; oftentimes, they are attacked, not for their beliefs but for their wealth.

Documented discrimination against Igbo Muslims

While the north burned, intolerance also took other forms in the country’s southeastern region. Minority Muslim residents, including Igbo indigenes, who practice Islam, face periodic attacks and persistent discrimination, such as institutional exclusion and social ostracism.

In Nsukka, Enugu State, mobs razed two mosques between Oct. 31, 2020 and Nov. 2, 2020, looting Muslim-owned shops after a local dispute spiralled. Though the state later rebuilt and returned the mosques to the Muslim community in 2021, the incident exposed how fragile interfaith coexistence remains.

Around the same period, in Afikpo, Ebonyi State, an Islamic school reportedly received threats of invasion, prompting nationwide Muslim organisations to condemn what they described as “a wave of attacks on Muslims in the South East”.

Beyond physical violence, Igbo Muslims speak of systemic discrimination in both public and social spheres. The Chief Imam of Imo State, Sheikh Suleiman Njoku, in March 2024, lamented how Muslim indigenes are stigmatised – denied marriage prospects, labelled traitors, and treated as outsiders in their ancestral communities.

Similar accounts featured in a 2021 Premium Times report, where Igbo Muslims detailed how even acquiring land to build mosques or express faith publicly invites suspicion and resistance.

Their testimonies mirror those of Christian minorities in majority-Muslim northern states, where churches are denied land ownership, leading to social alienation. There are also allegations of these minorities being denied state-of-origin certification.

This reciprocal intolerance across regions highlights a broader national crisis in which faith identity, rather than shared citizenship, continues to shape belonging, opportunity, and trust among Nigerians.

School segregation

In northern Nigeria, school segregation along religious lines has deeply eroded interfaith tolerance and national cohesion. Historically, Christian mission schools, Islamic schools and public institutions evolved in isolation, reflecting entrenched religious divisions rather than shared civic identity.

In many states, such as Kano, Kaduna, and Sokoto, Christian students often face discrimination or limited access to education in public schools dominated by Muslim administrators. Research shows that separate religious instruction – Christian Religious Knowledge (CRK) for Christians and Islamic Religious Knowledge (IRK) for Muslims —.has created parallel moral universes with little mutual understanding. This separation sustains mistrust and heightens communal suspicion.

The Deborah Samuel case in 2022, where a Christian student was lynched in Sokoto over alleged blasphemy, exemplifies how intolerance fostered from childhood schooling silos can erupt violently in adulthood. Studies by the EU Asylum Agency highlight that exclusion from inclusive schooling deprives youth of empathy across faiths, embedding prejudice into the social fabric. When children never learn together, they rarely learn tolerance. Unless education in northern Nigeria becomes deliberately integrative through mixed enrollment, pluralist curricula and interfaith engagement, religious segregation will continue to reproduce the fear, inequality and division that weaken Nigeria’s fragile unity.

Mass school abductions

Over the past 12 years, Nigeria has witnessed a series of mass school abductions that expose the evolving tactics of both terrorists and armed groups. Notably, on April 14, 2014, Boko Haram abducted 276 girls from Government Girls’ Secondary School, Chibok, Borno State, sparking the global #BringBackOurGirls campaign.

Years later, in February and March 2021, a wave of similar attacks swept across the north: 279 girls were taken from Government Girls’ Science Secondary School, Jangebe (Zamfara); 27 students and staff were kidnapped from Government Science College, Kagara (Niger); and 39 students were seized from the Federal College of Forestry Mechanisation, Afaka (Kaduna).

The cycle continued in March 2024, when gunmen abducted about 287 pupils from a school in Kuriga, Chikun Local Government Area, Kaduna State — one of the most significant of such incidents in recent years.

These abductions mark a clear shift from Boko Haram’s ideology-driven kidnappings to the ransom-motivated tactics of armed groups operating across the North West and North East. Christianity and Islam were affected by these abductions, and adherents have endured rape and psychological struggles following their ordeals.

Among these tragedies, Leah Sharibu’s story remains one of the most haunting.

On Feb. 19, 2018, the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), a Boko Haram offshoot, abducted 110 schoolgirls from Government Girls’ Science and Technical College, Dapchi, Yobe State. While most were later freed, Leah was held back for refusing to convert from Christianity to Islam. Now in her seventh year of captivity, she has become a symbol of religious persecution and the wider suffering of abducted girls. Her story underscores how Nigeria’s school kidnapping crisis intersects with issues of faith, gender and insurgency.

In contrast, Lillian Daniel’s ordeal highlights the hundreds of lesser-known victims whose abductions pass with minimal notice. The 20-year-old zoology student of the University of Maiduguri, originally from Barkin Ladi, Plateau State, was kidnapped on Jan. 9, 2020, while travelling along the Benisheikh–Jakana–Maiduguri road.

Her abductors were ISWAP terrorists who disguised themselves as security personnel. Another passenger was released, but Lillian remains missing. Her case, briefly reported but soon forgotten, reflects the anonymity of many victims caught in transit through conflict zones.

In summary, Leah Sharibu embodies the now globally recognised face of Nigeria’s school abduction crisis, shaped by ideology and prolonged captivity. At the same time, Lillian Daniel represents its hidden dimension — solitary, underreported, and tragically routine. Together, their stories reveal the spectacle and the silence of Nigeria’s enduring tragedy of school abductions.

When clergy became premium kidnapping targets.

Each ransom funds further raids. Analysts estimate that up to 15 per cent of ransom payments flow back into logistics for insurgents in Zamfara and Katsina.

Faith and identity: The shari’a factor revisited

The Shari’a revival was more than a legal reform; it was a reclamation of identity amid state collapse. Many Muslims saw it as a return to the moral order of the Sokoto Caliphate; others viewed it as the spark of two decades of religious strife.

Public institutions that once integrated faiths became segregated. Teachers and traders were attacked or expelled. The divide deepened, from classrooms to markets.

Shari’a, in principle, reserves blasphemy trials for qualified jurists. But in practice, mobs assumed divine authority, executing citizens in the name of faith. Many Christians and a few Muslims became victims of this street theocracy.

The justice vacuum

Out of the 20 worship-site attacks recorded, only one — Owo 2022 — reached federal arraignment. Fourteen remain unprosecuted; five are stalled as “unknown gunmen” cases.

On the Kano Central Mosque attack, no suspect has faced trial, while the Madalla bombing file remains “under review”.

“Justice in Nigeria moves slower than grief,” said a human rights lawyer in Abuja. “When the killers are never named, the dead are never remembered.”

Impunity has become policy. Each unsolved massacre guarantees the next.

A geography of grief

Nigeria’s worship-site attacks reveal a tragic spatial logic:

- North East (Borno, Yobe, Adamawa): Insurgent bombings, suicide IEDs, and procession attacks.

- North West (Katsina, Zamfara, Niger): Terrorists storming mosques during fajr prayers.

- North Central (Benue, Plateau, Kaduna): Reprisal killings and clergy kidnappings.

- South (Ondo, Anambra): Rare, symbolic assaults for national impact.

These are not frontlines of faith but fault lines of governance — places where the state’s absence defines daily life.

At a mosque in Konduga, the imam now carries a walkie-talkie. In a church in Makurdi, ushers rehearse evacuation drills. Security has become as sacred as scripture. Concrete barriers line entrances. Metal detectors hum where choirs once sang. Pastors rotate parishes weekly to confuse abductors.

“When we gather,” said a priest in southern Kaduna, “someone must always watch the door. It used to be an usher. Now it’s a man with a rifle.”

Multiple faces of mob justice, one failure of the state

Mob justice in Nigeria takes many forms. In the north, a whisper of blasphemy or even sexual orientation can summon a crowd to lynch anyone to death. In the south, a cry of “Ole” (thief) or even an allegation of witchcraft can become a death sentence, with tyres and fire replacing the courtroom and the judge.

The motives differ, but the barbarity does not.

Accused of robbing point of sale (PoS) machine operators, for instance, three women were burnt to death along the Aba-Owerri road in Aba, Abia State, on July 3, 2022. In March of this year, 16 hunters travelling from Rivers State capital Port Harcourt to Kano State were tied to used tyres and set ablaze in Uromi, Edo State, on suspicion of kidnapping.

What unites these episodes is a simple truth: they are crimes, yet their prosecutions are rare. That gap between law and practice isn’t a cultural quirk; its Local Security Equals High Fatality Rates.

Across faiths, executioners signal that citizens expect neither safety nor fairness from the state. Each unpunished lynching teaches the next crowd that there will be no price to pay.

Lessons in numbers

From 15 years of blood and rebuilding, four insights emerge:

- Predictable Patterns: Attacks cluster around worship hours and feast days.

- Declining Ideology: Ransom and revenge now outweigh religion.

- Governance Gaps: Weak local security equals high fatality rates — across faiths.

- Institutionalised Impunity: No justice, no deterrence.

Policy paralysis

Successive Nigerian administrations have treated worship-site attacks as isolated tragedies, not system failures. Troops arrive shortly after each attack. Condolences flow. Then silence.

“There is no single desk in Abuja tracking attacks on religious sites,” admitted a senior intelligence official. “The data is fragmented, politicised, and rarely analysed.”

Without institutional memory, the nation is condemned to repetition.

Reconstructing faith’s refuge

HumAngle analysts recommend modest, achievable reforms:

- Architectural retrofits: Two outward exits for every 150 congregants; Eid checkpoints relocated from dense zones.

- Safety training: Rotating volunteer marshals during peak services.

- Clergy protection: GPS-tracked parish vehicles and secure communications.

- Public case tracker: Government–media collaboration to document investigations and trials.

Each measure is a step toward rehumanising worship in a country where prayer itself is perilous.

Faith beyond fear

In Konduga, survivors of a 2013 mosque attack still gather under a patched tarpaulin. In Owo, St. Francis Church has reopened — some survivors sit by the very pews where they once fell to the ground.

“They wanted to destroy faith,” said Sister Agatha, who lost her niece in Owo. “But faith is the only thing that made us rebuild.”

Nigeria’s crisis of worship-site violence is neither a Christian nor a Muslim story. It is a national failure of protection and justice.

When a mosque burns in Borno and a church is bombed in Ondo, the message is the same: extremism recognises no creed. The silence that follows — the absence of trials, the forgetting of names — has become a form of complicity.

Faith in Nigeria today is more than belief. It is resistance — quiet, fearful, and defiant. From Madalla to Owo, from Kano to Katsina, the faithful still gather. Each whispered prayer in a bullet-scarred hall is an act of remembrance and a testament to resilience.

To remember both streams of suffering in one chronicle is to reject the propaganda of division. It is to insist that faith, stripped of politics, can still illuminate what violence seeks to obscure: our shared humanity.

Data collection by Abdussamad Ahmad Yusuf