When he was declared wanted in 2016, many teeth tattled that another man had “fallen into the Nigerian government’s net”. Accused of fraternising with Boko Haram terrorist leaders, Ahmad Salkida, then 41, left the United Arab Emirates (UAE) for Nigeria to clear his reputed name.

Salkida had left his country on self-exile to protect himself from the wrath of powerful people who wanted to silence him. After settling down with his family in Sharjah, UAE, he was compelled to return home to be grilled by the military. Those who were declared wanted in this manner were either charged with terrorist financing or treason.

Upon arrival, the military detained him for interrogation, after which the Department of State Security (DSS) took over. He was let go after ticking all the boxes proving his innocence. But how did a journalist known for revealing the clandestine operations of Boko Haram leaders end up in the trap net of authorities in the first place?

At a time when darkness overwhelmed northeastern Nigeria following the emergence of Boko Haram, Salkida persistently reported the human cost of insurgency in the region. He provided insights into the terror group’s inner workings through exclusive interviews, footage, and on-site reporting.

First, his reporting was stunning, providing intelligence about impending attacks and the Boko Haram Islamist conspiracies. Then, Salkida’s hyperlocal journalism style became a thorn in the flesh of those in power—as it exposed their lack of capacity to end the insurgency.

He had, for instance, alerted the authorities that Boko Haram was planning to deploy women and girls as suicide bombers. This warning would later manifest as described in Salkida’s reporting series. His exclusive interviews with Boko Haram’s founding leaders, Muhammad Yusuf and Abubakar Shekau, offered rare insights into the group’s rise at the time.

However, Salkida faced severe backlash for narrating stories that influenced media perceptions of Boko Haram’s actions.

In 2013, he disputed former President Goodluck Jonathan’s claim that Boko Haram insurgents were “ghosts.”

“They are human beings like us,” Salkida said. “I told you about my contact with many of them. So am I in contact with ghosts?”

He also questioned Jonathan’s efforts to negotiate with the group:

“When I single-handedly facilitated Datti Ahmed’s attempts to dialogue by the special Grace of God, did I have meetings with ghosts? Do Nigerians believe in ghosts?”

In 2015, Salkida again challenged the then-Chadian President Idriss Déby, who claimed that Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau was dead. “Idriss Déby is wrong now as before when he deceived former President Jonathan in phantom negotiation. Shekau is alive and leads ISWAP or Boko Haram,” he responded.

He also criticised former President Muhammadu Buhari’s handling of the Chibok schoolgirls’ abduction after Buhari claimed he had no intelligence on the girls.

“What happened to the video evidence former President Jonathan received less than two months into the abduction of the girls… or is everything Jonathan too dirty for this government to try its hands on?” he pondered on his social media handles. “My understanding of the Buhari administration as it relates to the negotiations of the abducted school girls is that they are living in a bubble. They want everything to work for them like ABCD: no hitches, no obstacles.”

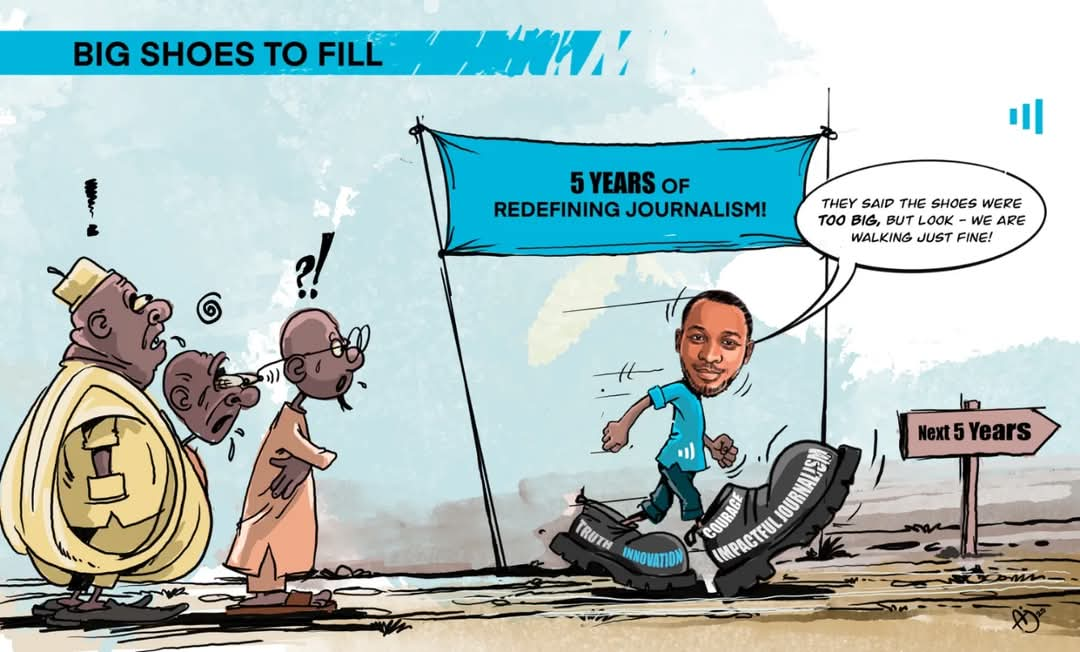

Like a football passed between amateur players, Salkida was played back and forth among authorities. He was forced out of the country and later repatriated, compromising his security. However, he turned adversity into opportunity. Four years after being declared wanted, he founded HumAngle to focus on conflict and humanitarian reporting in Africa.

A vision for conflict reporting

Established in March 2020, at the onset of the pandemic, by Salkida and Obiora Chukwumba, HumAngle has focused on covering the challenges faced by displaced persons, the insecurity in Nigeria’s northeast due to Boko Haram, and the organisations actively addressing these concerns.

“Our journey in this field is a pioneer work because this is the first time in Nigeria and the West African sub-region that any major platform was dedicating its entire vision and resources to reporting insecurity [and] humanitarian issues,” Chukwumba told the International Journalists’ Network. “Within six months of our operation, we reported the situation in northwest Nigeria as terrorism and not banditry. We did an editorial and gave examples and intelligence information.”

Back in 2017, Chukwumba said Salkida had discussed starting an outlet that would focus on insecurity, crises, violence, kidnappings, insurgency, displacement, and humanitarian issues across the country.

“Someone needs to constantly paint a picture of what these [issues] mean and connect with the voices of victims so that we will have a sense of where we are as a nation. That is part of what we have been doing,” Chukwumba said.

For Salkida, the HumAngle idea stemmed from his daily updates on insecurity and terrorism on social media, especially on X. He had mulled the idea of starting the platform in 2014 but as a general interest newsroom.

“Considering my long and rough experience with the Nigerian security sector, the escalating insecurity across the country, and the media blackhole surrounding various dimensions of the conflicts, it made more sense for it to be a niche platform,” HumAngle’s Founder and Editor-in-Chief said. “So, when I, together with Dr Obiora Chukwumba, founded HumAngle, the focus was to produce a unique platform that would predominantly report insecurity and conflict, starting with the Lake Chad countries.”

Six months into operations in 2020, HumAngle had broken the establishment barriers with media innovations, extensive storytelling, reliable and verifiable exclusive stories that shook the firmament of Nigeria, and appealing graphics and headlines that grabbed readers by the neck. However, the COVID-19 pandemic brought distress at a time when the HumAngle project was thriving, limiting its financial capabilities to operate at its maximum capacity.

The risks only escalated when Abubakar Shekau publicly threatened HumAngle and Salkida.

“Angle,” Shekau mispronounced the outlet’s name.

“Wallahi, you should listen. You, Salkida, whom we have known for a long time, wallahi, should be careful.”

Shekau, one of Boko Haram’s deadliest leaders, was responsible for some of Nigeria’s most horrific attacks and abductions. HumAngle later became the first newsroom to break the news of his death.

In an article titled ‘The Significance of September 6,’ Salkida vividly described how he moved from being declared wanted to shaping the HumAngle idea. He also reflected on his journey as a journalist in self-exile and his contribution to achieving peace and security in Nigeria.

“It is a battle I promised to fight with everything I had, and I couldn’t afford to lose. I firmly believe that one of the biggest loopholes the military used against me in 2016 was that I had no affiliation with any media institution beyond my microblog on Twitter. I was a freelance journalist, and freelance journalists are sitting ducks in this part of the world,” he reminisced.

Five years after its establishment, HumAngle has moved from being a microblogging platform to an innovative pan-African newsroom. Transitioning from just an idea, HumAngle Media became a newsroom with a diverse team focusing on insecurity and conflict in the region, using the most innovative solutions.

The last five years

What has HumAngle achieved in the past five years?

HumAngle has made significant impacts through its reporting and advocacy efforts, particularly its consistent coverage of vulnerable groups. Its reporting on the arbitrary detention of men accused of being Boko Haram members led to the release of hundreds of detainees, reuniting them with their families, including the Knifar Women who had been raising their children alone.

HumAngle’s crisis signalling efforts have provided early warnings to authorities, helping to mitigate crises. Its reporting has also influenced policy, as seen in the Federal High Court’s 2021 designation of certain armed groups in North West Nigeria as terrorists, a stance HumAngle had taken as early as June 2020.

Additionally, HumAngle’s work has been recognised through several awards, including the Wole Soyinka Award for Investigative Journalism, the Michael Elliott Award for Excellence in African Storytelling, and the Sigma Award, as well as being shortlisted for the African Fact-Checking Awards and the Livingston Award, and being named first runner-up in the CJID Awards.

“I am glad to have brought together and worked with a group of young men and women, a few of whom have left to start careers elsewhere. I am glad to have held up a conducive environment for them to be innovative and do things differently from the average newsroom in Nigeria. I am proud of the incredible work of my team,” Salkida said in a Sep. 6, 2021, article.

“I hope Nigeria and Africa will find the peace and security we yearn so much for but have been deprived of so that publications like HumAngle will move from reporting the impacts of wars to reporting the gains of peace.”