For over 15 years, the Nigerian government has engaged in one of the most protracted conflicts in Africa, fighting against Boko Haram, a notorious insurgent group seeking to establish an Islamic state in the country’s northeastern region.

The ruthless insurgent group and its splinter groups, including the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), have caused the death of almost 350,000 people as of 2020, according to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Aside from the recorded deaths, the conflict has also left deep scars, with millions displaced and several communities shattered. Despite extensive military efforts by Nigeria and the African Union (AU)-backed Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), the insurgents remain a potent force, striking fear into the hearts of civilians.

In the Northwestern region, several terror groups continue to wreak havoc across states like Zamfara, Sokoto, Kaduna, and Katsina. They engage in a range of crimes, including massacres, kidnappings for ransom, rape, cattle rustling, and the illegal possession of firearms.

With an estimate of over 30,000 terrorists spread across numerous groups in northwestern Nigeria, according to former Zamfara State governor Bello Matawalle, their violent actions have had a devastating impact. Since 2019, when their violence escalated, the terror groups have been responsible for the abduction and murder of an estimated 9,200 innocent civilians in the region.

In addition to the human toll, the activities of different terror groups have also had far-reaching economic consequences, as hundreds of commercial and farming enterprises have been reduced to rubble. Many health workers have been abducted with medical supplies for locals, and the trauma of loss and displacement has forever shattered thousands of people.

While the military recorded success last year, several notorious terrorist leaders who held sway in rural communities across the region, the conflict remains far from resolved. In fact, a terror group recently demanded over ₦200 million levy from communities in Zamfara, claiming it was ‘for peace to reign’. Failure to comply, they warned, would lead to violent attacks.

As state security agencies struggle to effectively respond to these challenges in the North West and North East, self-help militias have emerged. Some groups, often driven by desperation and a sense of abandonment, have taken it upon themselves to protect their communities from the relentless onslaught of terrorist groups.

The rise of self-help militias

The emergence of self-help militias in Nigeria has become a significant phenomenon in the country’s counterterrorism efforts, raising complex questions about the nature of security, governance, and the role of non-state actors in conflict resolution.

Since late 2013, one of the most prominent vigilante groups contributing to security efforts in the North East has been the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF). The group has been credited with providing valuable intelligence to security agencies, which has led to the arrest and prosecution of several Boko Haram suspects. They have also participated in joint operations with security agencies, resulting in the rescue of kidnapped victims and the recovery of stolen properties.

Aside from the CJTF, other groups, such as the Kesh Kesh vigilante group and the Vigilante Group of Nigeria (VGN), have also played significant roles. Though these militias have no legal standing, authorities continue to support their operations with multimillion-naira donations. Their involvement extends to assisting with the resettlement of internally displaced people (IDPs) and serving as community police for many local areas.

Some of these groups have lobbied for their formal legalisation and integration into state forces. At a press conference in May 2016, Nigeria’s former President Muhammadu Buhari recommended that “for those who have received military training, it will be advised either to recruit them if they are within the age bracket of recruitment in the military or the police.”

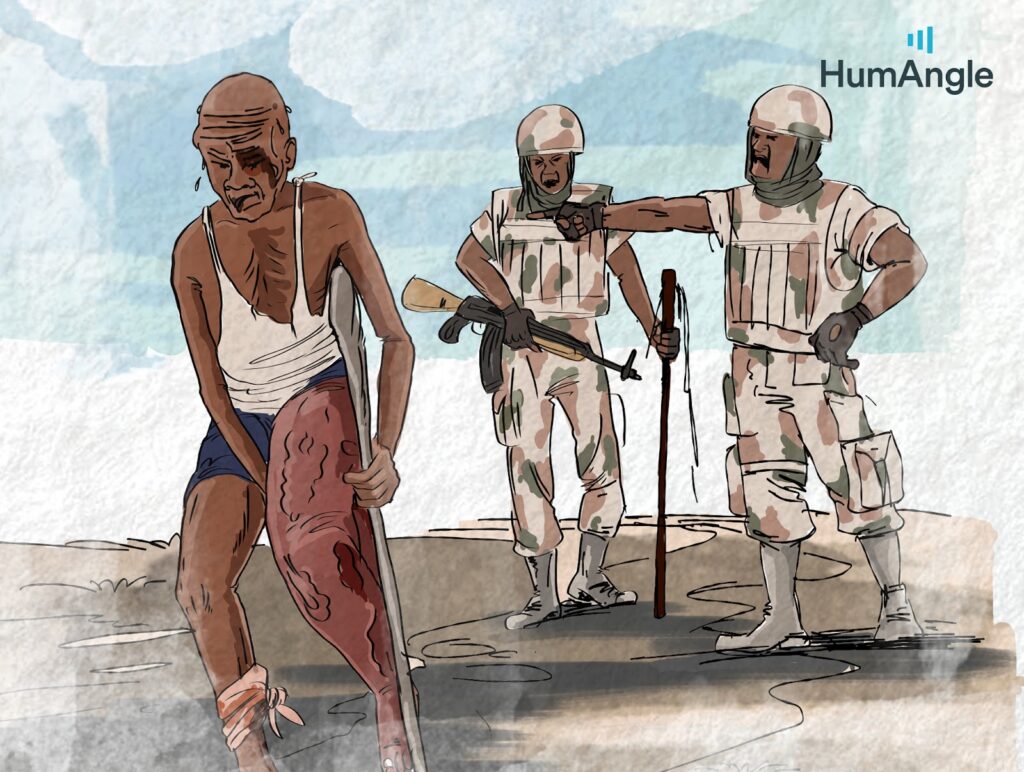

However, the rise of self-help militias presents serious challenges for local communities, particularly regarding accountability. While they provide essential security, they are not held accountable for their actions, including human rights abuses and impunity. In 2014, Amnesty International reported that CJTF was responsible for “grisly extrajudicial executions,” with video footage showing vigilantes slitting the throats of detainees alongside the army. HumAngle also obtained videos showing victims being forced to dig vast pits, after which security agents lined them up at the edge, one by one, and slaughtered them with crude machetes.

At Giwa Barracks in Maiduguri, many detainees were tortured to death in a manner so secretive that the victims’ families could not verify the fate of their arrested loved ones. Even when U.N. Special Rapporteur for Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions acknowledged that human rights violations had decreased in northeastern Nigeria in 2019, the Rapporteur stressed that accountability for past abuses—especially those committed during the conflict against Boko Haram—remained elusive.

Vigilantes take laws into their hands

Criminal elements, who make up only a tiny fraction of the Fulani population, have created a significant image problem for the entire ethnic group in the North West. The media have, at times, exacerbated this issue by blanketly labelling all criminal herders as “Fulani”.

This ethnic profiling has led to the murder of some innocent Fulani people by vigilante groups in the region, many of whom were killed for alleged involvement in terrorism simply because they belonged to the Fulani ethnic group. Despite being victims themselves, they are being stigmatised and ostracised by other communities. The stories of those who spoke to HumAngle revealed a complex web of suffering, where entire communities are being unfairly judged and punished for the actions of a few. As the abuse of these innocent people by self-help militias intensifies, they are seeking to rebuild their lives and restore their dignity.

Legal experts have also raised concern about the involvement of vigilante groups in Nigeria’s security landscape, explaining that they often encroach on the constitutional duties of state security agencies. Even locals interested in the harassment of others employ their services and embolden them to take the laws into their own hands.

“The encroachment on constitutional duties of state security forces has significant implications for the rule of law, accountability, and human rights,” said Suleman Akano, a legal practitioner. “The Nigerian Constitution is clear about the roles and responsibilities of state security agencies. We all know that the police are constitutionally mandated to maintain law and order, while the military is responsible for defending the country’s territorial integrity.”

“How do we explain the role of self-help militias that are not constitutionally recognised? It would be difficult to be subject to the same level of accountability and oversight as state security agencies. Without proper oversight, they will continue to engage in extrajudicial killings, which undermines the rule of law,” the lawyer explained.

Proliferation of firearms

According to a United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR) research, about 55,000 self-help militias (otherwise referred to as Volunteer Security Outfits, VSOs) possess roughly 25,000 firearms in northeastern Nigeria.

Eric Berman, the Director of Safeguarding Security Sector Stockpiles, said these firearms include domestically-made dane guns, foreign-manufactured hunting rifles and pump-action shotguns. Some are also said to own industrially produced assault rifles, which were mostly recovered from battlefields with the insurgents.

The UNIDIR research raised concern about the extent to which legal and regulatory frameworks, including the 1959 Firearms Act, are being followed when it comes to arming these groups. “In some cases, the arming of VSO members resembles basic training for military conscripts, rather than an authorisation process for civilian possession of firearms. Overall, it has proven challenging to understand the conditions imposed on recipients of assault rifles,” part of the research read.

Berman, in the research, mentioned that efforts to account for arms provided to self-help militias between 2015 and 2019 proved abortive, explaining that authorities seemed to prioritise the security situation in the region over adhering to the 1959 Firearms Act, which prohibits providing most types firearms to civilians. Following the development, officials failed to follow record-keeping practices, making it difficult to understand the scope of firearms management.

What happens after insurgency?

The question that weighs heavily on the minds of analysts, policymakers, and citizens is: “what will be the fate of the militias and their weapons after insurgency?” The most definite answer is deeply concerning. If left unchecked, these groups could significantly threaten national security, stability, and the rule of law. The widespread availability of weapons in their possession has the potential to fuel further violence, crime, and instability.

At the time of filing this report, there’s no clear plan for demobilisation, disarmament and reintegration. Hence, some militias with records of human rights abuses may turn to criminal activities.

To mitigate these risks, the Nigerian government must develop a comprehensive plan to address the fate of the militias and their weapons. Key recommendations from the UNIDIR research: there’s a need to clarify the types of weapons provided to militias, their documentation, and measures to avoid misuse and diversion. The research also urged authorities to check the number of firearms distributed to militias with each Divisional Police Officer (DPO) and the number of weapons still held by those who have received them.

The research also advised the military to mark firearms provided to militias based on Article 18 of the ECOWAS Convention on Small Arms and Light Weapons (SALW) Convention, and also keep details about distributed firearms in a “centralised secure database or register in accordance with Articles 9 and 14 of the ECOWAS SALW Convention. Additional information to include in the database can include the location of the arms.”

Although the National Centre for the Control of Small Arms and Light Weapons has yet to respond to HumAngle’s enquiries about records of small arms and weapons in the country, the government must strengthen state security agencies. Experts say these agencies must be held accountable to the public, and self-help militias should be regulated appropriately to ensure they do not undermine the constitutional responsibilities of state security forces.