On a cold December morning in 1931, a short, elderly Black woman set out on a 24km (15-mile) walk from her homestead in Alabama, United States, on a quest for justice. The long trek to the court in Selma was no small undertaking for a person in her mid-70s. But Matilda McCrear was determined to go and make her legal claim for compensation for the horrors that she and her family had been through.

Until her death 85 years ago on January 13, 1940, Matilda was the last surviving passenger on the last-ever slave ship bound from the West African coast to North America in late 1859.

Her story began many decades before and thousands of miles away from that sharecropping homestead. Originally named Abake – “born to be loved by all” – the girl later renamed Matilda by her American “owner” came into the world circa 1857, among the Tarkar people of the West African interior.

In 1859, at the age of two, little Abake was captured along with her mother (later renamed Grace), her three older sisters and some other relatives, by troops of the Kingdom of Dahomey, located in what is now Benin. Torn away from the rest of their family, they were victims of an age-old regional warfare which underpinned an equally ancient but persistent trade in slavery reaching across North and East Africa, the Ottoman Empire and eventually the Americas.

The precise details of her capture are unknown but, like millions before them, Abake and the other captives were very likely tied together in groups, with ropes and wooden yokes, and forced to march hundreds of miles to the coastal port of Ouidah, now a city in southern Benin. Their so-called “death march” was the first leg of a long and merciless sojourn.

Once they arrived in Ouidah, slaves would be held in “barracoons” – enclosed pens within which prisoners awaited inspection and sale to European traders, at which point they were often branded with the dehumanising mark of their new owner.

Abake and her family members were sold as part of a consignment of slaves to one Captain William Foster, of Canadian origin. He wrote in his journal: “I went to see the King of Dahomey. Having agreeably transacted [our] affairs … we went to the warehouse where they had in confinement four thousand captives in a state of nudity from which they gave me liberty to select one hundred and twenty-five as mine, offering to brand them for me, from which I preemptorily forbid [sic]; commenced taking on cargo of negroes, successfully securing on board one hundred and ten.”

Foster’s ship, Clotilda – a two-masted schooner, 26 metres (86 feet) in length – is now infamous as the last ship known to have carried slaves across the Atlantic to North America. By this time it was an illegal journey, for while slavery continued across the southeast of the US (and in parts of South America), the importation of slaves had been prohibited since 1808. The Clotilda set sail from Ouidah late in the year, purportedly carrying lumber – the 11-man crew being promised double their normal wage to keep quiet about the true contents, as per an entry in Foster’s journal.

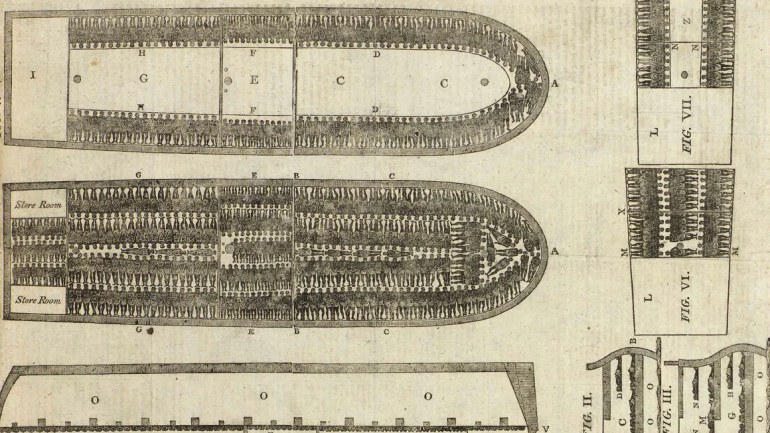

Their route across the Atlantic was known as the “Middle Passage”, making up the second part of a triangular trade route connecting Europe, Africa and the Americas. Ships carried weapons and manufactured goods from Europe to the “slave coast” of West Africa on the first part of the round trip; in the Middle Passage, that cargo was traded for enslaved Africans who were transported to the US and South America, where they were usually sold by auction; and on the final course, the vessels returned to Europe usually laden with cotton, tobacco and sugarcane.

The Middle Passage was a horrific journey lasting some 80 days, during which the human cargo endured cramped and filthy conditions. In the autobiography of an 18th-century slave, Olaudah Equiano, one slaving ship is described as being “so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocating us. This produced copious perspirations, so that the air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died.”

Separated and sold – a brutal but common fate

Of the approximately 12.5 million enslaved Africans transported to the Americas over some 350 years, it is estimated that at least two million souls perished during the crossing over the Atlantic. Grace would later tell her daughters how she had witnessed her nephew and others from her Tarkar village being simply thrown overboard when they became unwell, apparently to prevent any contagion.

Foster navigated the Clotilda, now carrying 108 slaves, into the port of Mobile, Alabama under cover of darkness in early 1860. He had it towed up the Mobile River to Twelvemile Island, where the captive Africans were transferred to a river steamboat. Foster wrote in his journal that the Clotilda was then burned to destroy any evidence.

Foster was ultimately prosecuted in 1861 for illegal slave importation, but the case was dismissed for lack of evidence from the ship or its manifest. It was not until 2019 that researchers found the remains of the Clotilda in the Mobile River, confirming its existence and location.

At Twelvemile Island, Abake, her mother and her 10-year-old sister were handed over by Foster to one of the financial backers of Clotilda, a wealthy plantation owner by the name of Memorable Creagh.

In another heartbreaking separation, Abake’s two other sisters (whose names are unknown) were sent elsewhere, never to be seen again – a typically brutal fate for so many of those regarded as a mere commodity.

Abake, her mother, and her sister soon found themselves on Creagh’s plantation near Montgomery, Alabama. There, Abake was given the new forename Matilda, her mother was renamed Grace, and her sister as Sally. Grace was forcibly married to a fellow survivor of the Clotilda, who had been renamed Guy.

Because the couple were classed as “property”, their marriage was not recognised by law; it was simply a means of producing more slave offspring. Even the intimacy of a man and a woman was subject to the absolute control of slave-owners. Grace and Guy were given the surname of their new owner and put to work in his cotton fields.

Matilda’s family were likely provided with the most basic kind of shelter, crammed with other families into crude wooden cabins that were leaky in wet weather and cold in the winter, and forced by their overseers to work seven days a week.

The adult Matilda had only a hazy recollection of those early years, but later recalled one episode when, aged three, she and her sister Sally escaped from the plantation to a nearby swamp where they were scented out by the overseer’s dogs and returned to their quarters.

Matilda was still a small child when the Civil War broke out in the US in April 1861. Alabama, along with Virginia, North and South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas and Tennessee, seceded from the US and formed the Confederate States of America – on the grounds that the institution of slavery, the lifeblood of southern economies, was threatened by the federal government in Washington.

President Abraham Lincoln made his Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, declaring that all enslaved people in the Confederate states were free. This had no immediate effect on Matilda and her family, as the Civil War continued to rage. But when the Confederates were defeated on June 19, 1865, Matilda and her family were liberated.

Matilda would have been about seven years old at this time. Her family headed north and settled in Athens, Alabama. It is not known how they supported themselves. Matilda later related how she learned English quickly as a small child and would help interpret for her mother and stepfather, who faced challenges with this new language.

They were free, but what would that so-called freedom mean?

Slavery in all but name

However harsh and unjust the circumstances, enslaved people had some small element of security. A slave owner was at least motivated to ensure the good health of his human chattels to ensure their productivity, which necessitated the provision of food and basic shelter.

But after 1865, freed slaves did not find themselves in a friendly world. Many white Americans reacted with indignant fury to the idea of Black people being their equals. In a harsh and unwelcoming world, there were few options for uneducated ex-slaves other than to remain on the plantations as “sharecroppers” – a system whereby a tenant farmed a portion of land in exchange for a share of the crop. Sharecropping often involved contracts that trapped tenants in debt and poverty and which in practice was not far removed from actual slavery.

Upon her emancipation, Matilda and her family thus became supposedly free people. But, as Martin Luther King Jr pointed out in a 1968 sermon, “Emancipation for the Negro was only a proclamation. It was not a fact. The Negro still lives in chains: the chains of economic slavery, the chains of social segregation, the chains of political disenfranchisement.”

During the post-Civil War period of “Reconstruction”, many new federal laws promoting racial equality were quickly met by local state measures designed to keep Black people “in their place” and ensure that white people remained ascendant. This is seen in the reaction, at the state level, to the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the US Constitution.

The 13th Amendment of 1865 officially ended slavery in all US states and territories. Formerly enslaved people were legally freed, while the Freedmen’s Bureau was established to aid freed slaves through the provision of food, housing, medical aid, schooling and legal support.

To counter this, southern states, including Matilda’s home of Alabama, enacted the so-called “Black Codes”, curtailing the right of African Americans to own property, conduct business, buy and lease land or move freely in public spaces. The Black Codes forced many Black people into newly exploitative labour arrangements such as sharecropping.

A central element of the Black Codes was “vagrancy” laws. Through a system known as “convict leasing”, many African-American boys and men were arrested for minor offences such as vagrancy, imprisoned, and then leased out to work for private businesses. This created a new system of forced labour which again was little more than slavery. Convict leasing was legally rooted in the so-called “exception clause” of the 13th Amendment which states, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States.”

Convict leasing is prevalent in the US to this very day, with most working prisoners – still overwhelmingly Black and Hispanic – being paid only a few cents per hour. And even upon their release, ex-convicts have always faced immense hurdles to finding employment, getting credit, doing business or buying property due to their prison records.

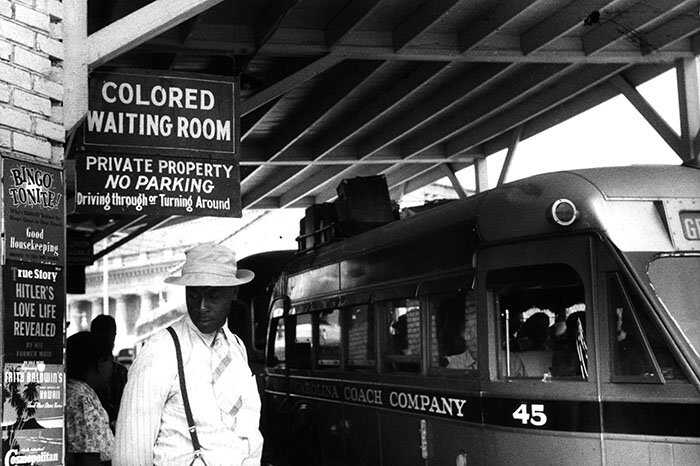

The 14th Amendment of 1868 granted full US citizenship to African Americans, with states being legally required to provide equal protection under the law. One response to this was the “separate but equal” ruling in the landmark 1896 case of Plessy v Ferguson, which legalised racial segregation in the public sphere. A New Orleans man by the name of Homer Plessy, who was one-eighth Black, had refused to sit in a train car designated for Black people. Plessy was arrested and claimed that his 14th Amendment rights were being contravened.

The case went to the Supreme Court, which infamously ruled that racial segregation laws did not violate the US Constitution as long as the facilities for African Americans were equal in quality to those of white people.

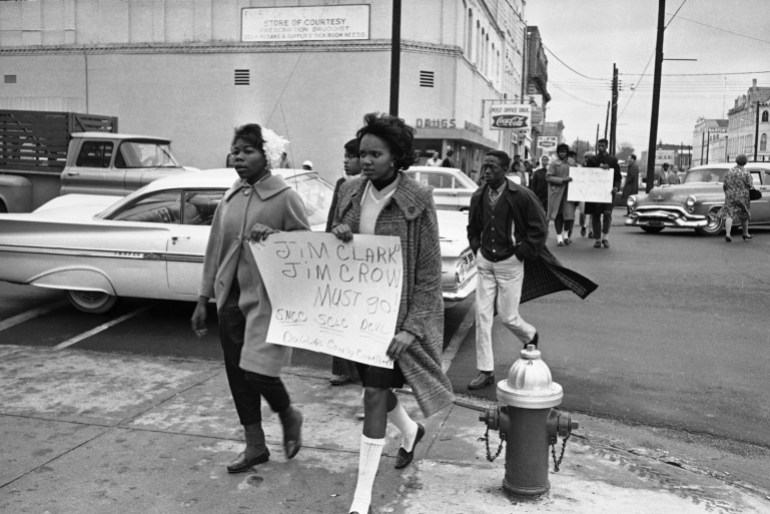

The Plessy ruling ushered in a raft of so-called “Jim Crow” laws, which reinforced racial segregation across the American South right up until the 1960s. Stemming from a derogatory term for an African American, these laws mandated separate schools and transport, effectively denied African Americans the right to vote, outlawed interracial marriage and introduced the use of signage such as “Whites Only” to enforce the racist order.

And while the 15th Amendment of 1869 prohibited the federal and state governments from denying citizens the right to vote based on “race, colour, or previous condition of servitude”, it was countered by manipulative practices such as literacy tests, poll taxes and so-called “grandfather clauses” which restricted voting rights to men who had been able to vote or whose male ancestors could vote prior to 1867.

While the Jim Crow statutes were in theory meant to provide “separate but equal” treatment of white and Black peoples, in practice, African Americans received far inferior treatment; and concurrent with these laws were other forms of societal racism, for example barring the “wrong type” of people from clubs and institutions, city planning measures ensuring that Black people remained on the “other side of the tracks”, and “redlining” by banks whereby credit was denied to the inhabitants of Black-majority neighbourhoods.

Even places of worship were strictly segregated according to the colour of their congregations. Indeed, novelist James Baldwin noted in 1968, almost a century after the 15th Amendment was passed, “…we have a Christian church which is white and a Christian church which is black … [and] the most segregated hour in American life is high noon on Sunday.”

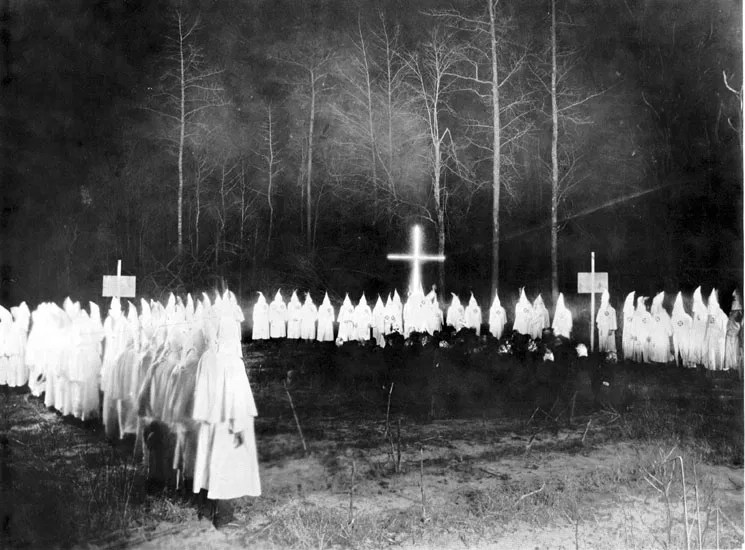

All these laws, policies and social attitudes were enforced, frequently with extreme violence, by white supremacist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, often with the direct or tacit support of the police.

Such were the harsh conditions in which Matilda grew up. Her childhood ended abruptly at the age of 14, when she first gave birth, likely as the result of rape, given the prevalence of white male sexual violence towards Black girls and women in the south at that time.

Matilda later entered a common-law partnership with a German-born man called Jacob Schuler and had a total of 14 children, 10 of whom survived into adulthood. What befell the other four is unknown. Whether she was prevented from marrying her partner by the ban on interracial marriage, or chose that arrangement, is also not known. In any case, Matilda appears not to have benefitted financially from the relationship, as she remained a sharecropper, living in the vicinity of Selma, Alabama, for most of her working life. At some point, she changed her surname from Creagh to McCrear, perhaps to distance herself from her enslaver and as an assertion of her own identity. Over the generations, the family surname has seen a number of further variations, including Crear, Creah, Creagher and McCreer.

Waiting all her life for justice that never came

In 1931, Matilda heard a rumour that people like her were receiving compensation for being illegally smuggled as slaves into the US. That was when she decided to embark upon the 15-mile journey on foot to the Selma court in Alabama to make her claim.

The judge declared the rumour to be “false” and dismissed her case. But fortunately for modern historians, an account of her lawsuit was published by the Selma Times-Journal. This was the article discovered by Hannah Durkin, a Newcastle University historian specialising in the transatlantic slave trade and author of the 2024 book, Survivors: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the Atlantic Slave Trade.

The Selma Times-Journal news story provides a vivid description of Matilda: “She walks with a vigorous stride. Her kinky hair is almost white and is plaited in small tufts and with bright-coloured string … Her voice is low and husky, but clear. Age shows most in her eyes … yet her … skin is firm and smooth.”

The article went on to relate that “Tildy has vigor and spirit in spite of her years … endurance and a natural aptitude for agriculture inherited from the Tarkar tribe, made [her] a thrifty farmer.”

Durkin writes that Matilda’s story is particularly remarkable “because she resisted what was expected of a Black woman in the US South in the years after emancipation. She did not get married. Instead, she had a decades-long common-law marriage … Even though she left West Africa when she was a toddler, she appears throughout her life to have worn her hair in a traditional Yoruba style, a style presumably taught to her by her mother.”

Matilda fell ill after a stroke and died at the age of 83 on January 13, 1940.

One participant at Matilda’s funeral was her little grandson, John Crear. “I was about three years old and I got away from my parents and almost fell in the grave,” he told National Geographic in 2020.

John Crear, a retired hospital administrator and community leader now in his late 80s, was born in the house Matilda resided in, and her funeral is one of his earliest memories. His grandmother’s strong character apparently passed into family lore. “I was told she was quite rambunctious”, he said.

He discovered more about Matilda when he and his wife carried out some research of their own into the family history. “I had no idea she’d been on the Clotilda”, he said. “It came as a real surprise. Her story gives me mixed emotions because if she hadn’t been brought here, I wouldn’t be here. But it’s hard to read about what she experienced.”

Matilda waited all her life for some form of justice and it would be another 14 years before the civil rights movement began to challenge the systemic racism she faced. Iconic leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X pointed out the hypocritical gap between the ideals of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments and the actual lived reality of African Americans.

In a 1964 speech, Malcolm X demanded: “… our right on this earth … to be respected as a human being, to be given the rights of a human being in this society … which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary.”

Although Matilda missed out on witnessing any of this, her grandson was active in the civil rights movement. “You can read about slavery and be detached from it,” he told National Geographic. “But when it’s your family that is involved, it becomes up close and very real.” During the Civil Rights movement, he was arrested and imprisoned on charges of assault and battery – for the offence of stopping a white man who attempted to stuff a live snake down his throat.

Indeed, many civil rights campaigners faced extreme violence from the police and the National Guard, leaving many injured, imprisoned or even dead, as in the case of both Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X.

But their sacrifices were not in vain. By the mid-1960s, the entire plethora of Jim Crow statutes had been taken down. Segregation in public schools was deemed unconstitutional in the 1954 case of Brown v Board of Education; discriminatory electoral practices such as literacy tests and grandfather clauses were banned by the Voting Rights Act of 1965; and all other forms of segregation and employment discrimination were outlawed by the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

These were statutory measures aiming to eradicate prejudice in the official sphere. However positive their effect, deeper-rooted racism at the societal level remains a feature of US life. “As long as people can be judged by the colour of their skin, the problem is not solved,” talk show host Oprah Winfrey said in 2021.

Ninety years before that, Matilda seemed to recognise this when she seemed unsurprised by the Selma court’s denial of her claim for compensation.

“I don’t expect I need anything more than I got,” she said after thanking the judge for his time.