Welcome to the L.A. Times Book Club newsletter.

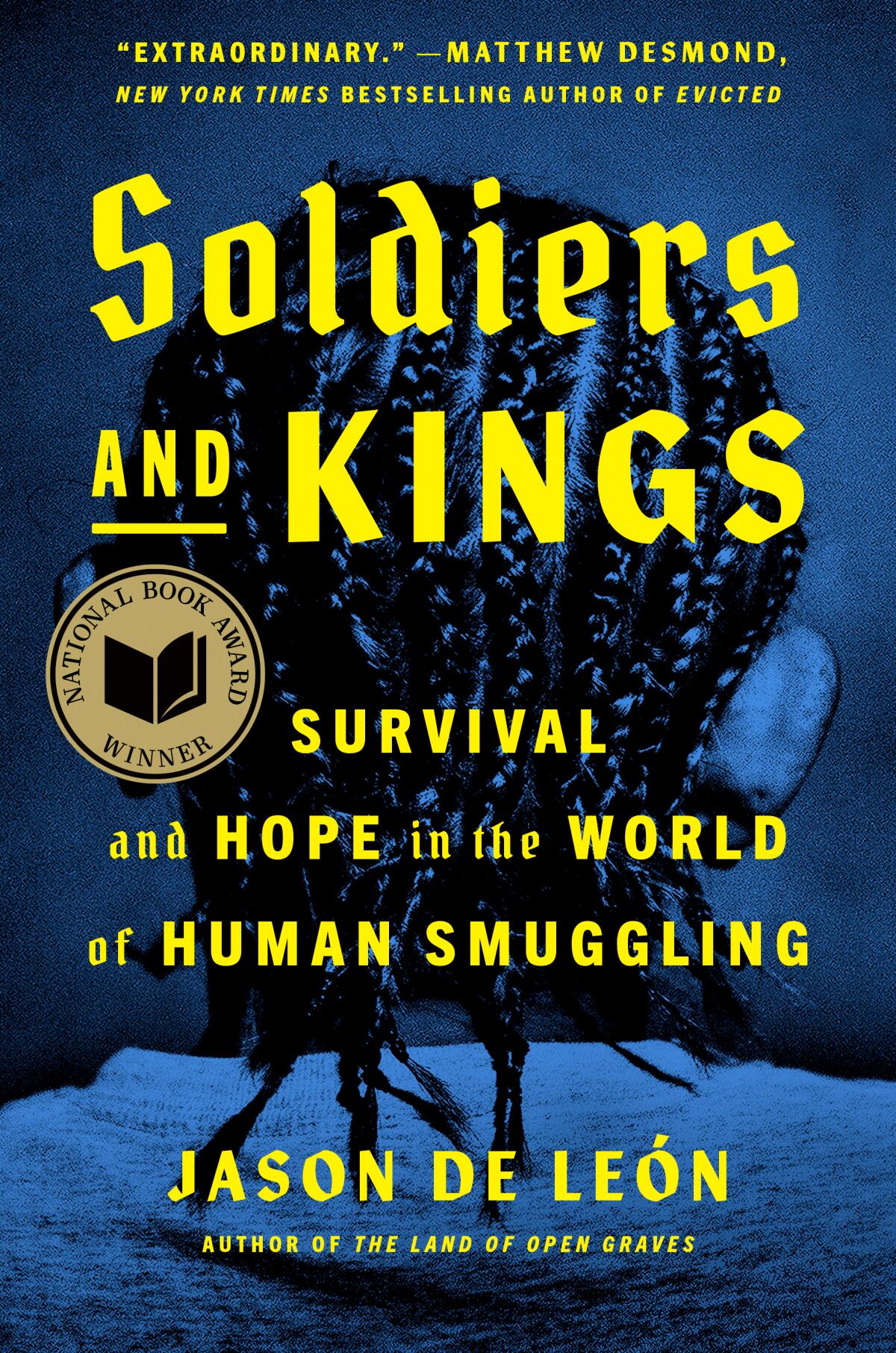

Hello, fellow readers. I’m culture critic and fervent bookworm Chris Vognar. This week we speak with lifelong Angeleno Jason De Leon, whose book “Soldiers and Kings,” a harrowing and deeply empathetic study of smugglers guiding migrants (mostly Central American) across Mexico, recently won the National Book Award for nonfiction. We also look at recent releases reviewed by Times critics and take a look at other stories about those who undertake arduous border passages.

Over a period of seven years, De Leon, a professor of anthropology, spent time embedded with a group of people like those depicted in his book.“That’s pretty standard for any kind of ethnographic project,” he said. “These are long-term time commitments. So when I began the project, I knew that it was going to be for the long haul.”

At a time when debates over immigration often carry more noise than substance, “Soldiers and Kings” puts the reader on the ground, among real people with real stories. I spoke with De Leon — a professor of Chicana, Chicano and Central American Studies in addition to anthropology at UCLA — about building trust, the difference between smuggling and trafficking, and what it is exactly that an anthropologist does.

We’re trying to understand the human condition from as many different perspectives as possible.

— Jason De Leon, author of “Soldiers and Kings”

Jason De Leon writes about his ethnographic study of human smugglers in his book “Soldiers and Kings.”

(Viking)

You spent a lot of time in some pretty dangerous situations working on this book. Trust must be an important part of that day-to-day process.

Yeah, you’re dealing with a lot of sketchy folks. I just really had to trust the people that I was working with and writing about. I don’t want to call it blind trust because you kind of figure out as you’re going who to trust, how much to trust. But there really is a bit of a leap of faith that these folks are going to take care of me at the end of the day. So I really had to work to find the right people that I thought I could spend time with, and people who understood the project and who really wanted to show me as much as they possibly could.

These are people whose lives depend on being able to read the room correctly. So when I walk into this space and say, “Hey, I’m an anthropologist, I want to be here, I want to record everything,” they have to make a pretty quick assessment of whether or not I’m a threat, and how much they trust me.

What are common misconceptions about human smugglers?

It feels like 90% of the time people conflate trafficking with smuggling, and they are two radically different things that get used interchangeably. People who are trafficked have that happen against their will. And people who are smuggled are paying someone to get them to where they want to go. That’s a huge misconception, and it’s one that really undermines our ability to understand what smuggling is and how it actually functions globally.

How does Los Angeles play a part in the book?

It shows up in the book in different ways. One of the main guys that I write about was a Honduran who settled in L.A. after Hurricane Katrina. He ends up joining [the international criminal gang] MS-13. He sort of has this kind of MacArthur Park L.A. experience and gets deported and sent back to Honduras after being incarcerated in California, and he sort of falls in with these smugglers, For me, there were different moments in the book where Los Angeles would come up on the train tracks in southern Mexico or in Honduras.

You have devoted your life to anthropology. How would you describe the field to someone who is unfamiliar?

We’re trying to understand the human condition from as many different perspectives as possible, whether that’s through ethnographic work, or working with contemporary people, or through archeology or through linguistics. All of the different things that anthropologists do are attempts to understand humans. We really try to make the familiar strange and the strange familiar. We look at the world from different perspectives as a way to kind of shine a light on what’s actually happening.

(Please note: The Times may earn a commission through links to Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.)

Newsletter

You’re reading Book Club

An exclusive look at what we’re reading, book club events and our latest author interviews.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The week(s) in books

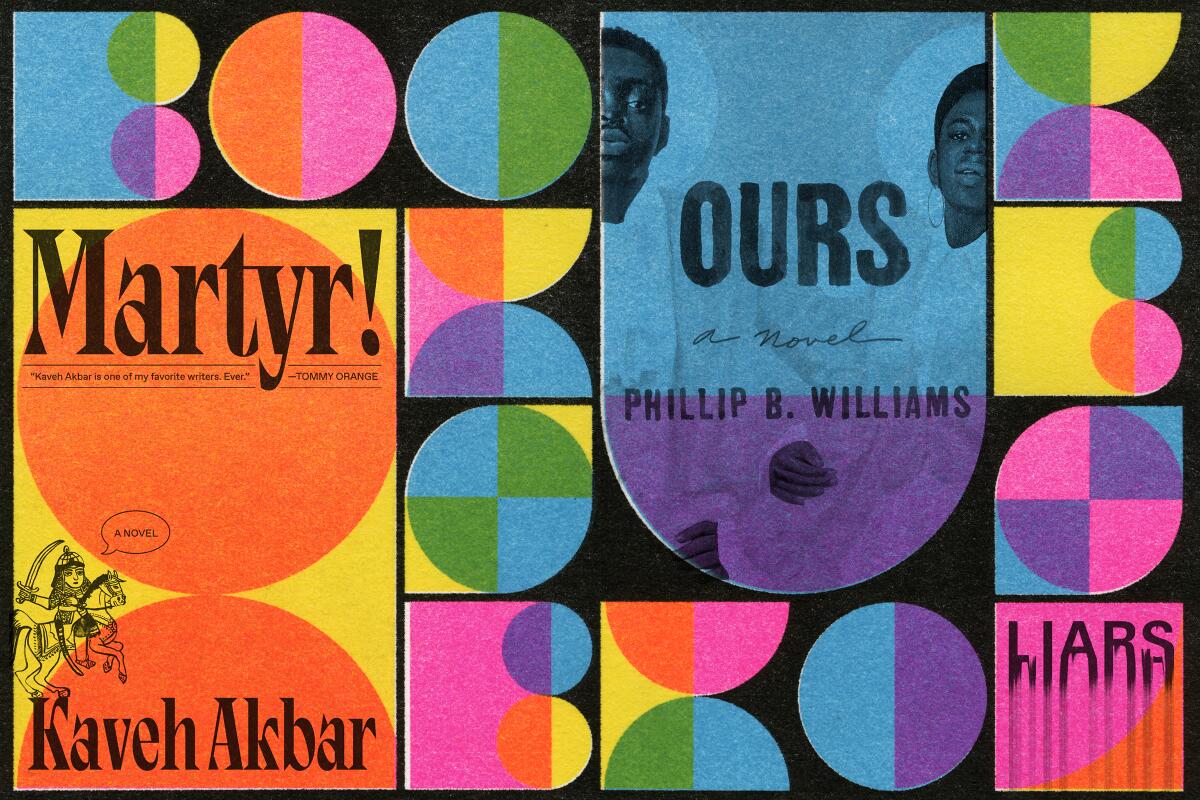

We asked three of our book critics for their favorite books of 2024. Here are their picks.

(Illustration by Julia Schimautz / For The Times. Images by Knopf, Viking and Hogarth.)

Times critics pick the 15 best books of 2024.

Charles Arrowsmith reviews Anita Felicelli’s story collection “How We Know Our Time Travelers.” “Though these 14 miniature crises contain numerous fantastical or science-fictional elements,” Arrowsmith writes, “they are fundamentally explorations of this stubborn, very human attachment to things that cannot be.”

Mark Athitakis reviews “Sleepaway,” the new novel by Kevin Prufer. In this dystopian vision, Athitakis writes, “Instead of abject peril, humanity is thrust into a state of anxiety, like being stuck in the middle of a wobbly bridge.”

Jenny Gold writes about book bans’ frightening chill on children’s book sales. “During the 2023-24 school year, there were more than 10,000 book bans in public schools — a 200% rise over the previous year,” Gold writes.

And Gustavo Arellano looks at recent books by and about Southern California Latinas, ranging from “a history of gangs in East L.A. to a gorgeous coffee table tome about the cult classic ‘Blood In Blood Out’ to a delightful children’s tale on the late Los Angeles Dodgers legend Fernando Valenzuela.”

Crossing

Gregory Nava’s 1983 film depicts siblings making their way from Guatemala to Los Angeles.

(Cinecom International Films)

“Soldiers and Kings” is one of many books about the perils and realities of crossing borders. Here are some of the essentials.

“Solito,” by Javier Zamora: A potent and poetic memoir about a 9-year-old’s harrowing trek from El Salvador through Guatemala, Mexico and, finally, the U.S.

“The Crossing,” by Cormac McCarthy: A boy, a wolf, and a journey to Mexico, rendered in incandescent prose.

“Crossing the Line: Finding America in the Borderlands,” by Sarah Towle: Towle takes on the broken U.S. immigration system, focusing on the human rights trampled amid the rubble.

“Signs Preceding the End of the World,” by Yuri Herrera: A short novel about the border as both physical space and state of mind.

“El Norte,” directed by Gregory Nava: OK, so this one is a film. But its depiction of a brother and sister making their way from Guatemala to Los Angeles, and what is lost once they arrive, is both timeless and timely.

That’s all for now. Keep turning those pages.