MICHAEL Booth watched dementia slowly rob his mum of her ability to talk or identify objects before she eventually died in 2020.

Months later, he too was diagnosed with the condition – aged just 46.

Michael, from Hartlepool, County Durham, said: “The diagnosis was a real blow, especially as I’d just watched my mum go through it.

“One of the hardest parts was to tell my dad that, after losing his wife to dementia, I now had it too.

“It felt like a kick in the stomach at the time, and still does.

“It’s a terminal disease, there is no cure, so it was a case of coming to terms with it.”

Eventually, Michael came to accept his fate and now gives talks around the world on early-onset dementia.

He has also written a book on the condition, and works with Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust.

The author of Dementia: You Are Not Alone said: “If the book helps just one person, either someone with Alzheimer’s or their carer, to accept the disease and live the best they can, then as far as I’m concerned, it has done its job.”

Michael was born in the North East but moved to South Africa as a child.

He returned to the UK when his grandfather developed what appeared to be dementia.

“Although it was a sad situation, my grandfather was in his 80s at the time – an age when you might expect people to have some loss of memory function,” he said.

“He never got a formal Alzheimer’s diagnosis, but he did have the symptoms.

“None of the family realised back then that the disease could be genetic.”

Michael’s mother, Christine, started struggling with her mental health not long afterwards, when she was in her early 50s.

Initially, her loss of speech was put down to stress and anxiety.

Eventually, aged 55, she was diagnosed with young-onset Alzheimer’s – by which time she couldn’t talk or identify objects and was losing her memories quite rapidly.

“I helped my dad care for my mum and, as time went on, I found myself forgetting where I was going, forgetting my words and having problems with my balance,” Michael said.

“My mum was in palliative care by this time, and I put it down to stress.

“But one of the Trust mental health nurses caring for my mum suggested I get tested, so I did.”

I thought I had a whole future ahead of me, until I didn’t

Michael Booth

Christine died just before the first Covid lockdown of 2020, at the age of 65.

Only a few months later, Michael received his own devastating diagnosis.

“I was 46 at the time – an age where I thought I had a whole future ahead of me, until I didn’t,” he said.

“Strangely, the peace of the Covid lockdowns helped me come to terms with my health.

“Lockdown gave me a chance to reflect and research.

“I had lost my driving licence with the diagnosis, couldn’t work and it was a lot to deal with, but my wife was such a great support.”

Michael, a former project manager, found that his speech and balance, rather than memory, were affected at the start of his illness.

He often forgot, or got stuck on, words while talking.

His balance issues also landed him in A&E with broken bones on several occasions, which prompted The Bridge dementia charity in Hartlepool to suggest he move to assisted housing.

CHANGE OF DIRECTION

“After the move, The Bridge asked me to write about my experiences,” Michael said.

“I thought about it for a while and, once I started writing, I never stopped. That work has become my book.

“Writing gave me something to do at first, helped keep my brain active – then I realised it might help other people in the same situation as me. I really hope it does.”

Michael has drawn on the expertise of those he has met while giving talks and volunteering for charities to ensure his book is both factual and practical.

It is now available on Amazon and has been written as a guide to the support, help and advice which has helped Michael on his dementia journey.

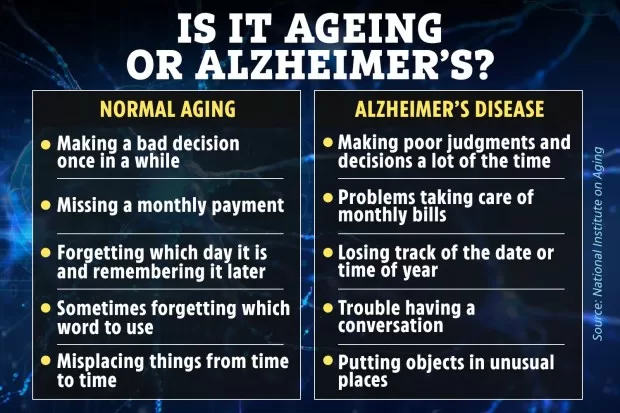

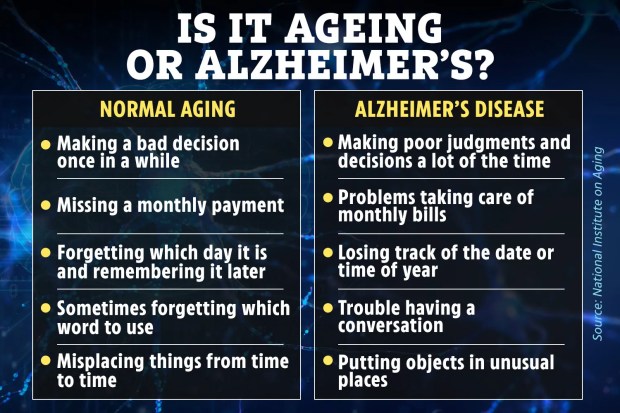

Is it ageing or dementia?

Dementia – the most common form of which is Alzheimer’s – comes on slowly over time.

As the disease progresses, symptoms can become more severe.

But at the beginning, the symptoms can be subtle or mistaken for normal memory issues related to ageing.

The US National Institute on Aging gives some examples of what is considered normal forgetfulness in old age, and dementia disease.

You can refer to these above.

For example, it is normal for an ageing person to forget which word to use from time-to-time, but difficulting having conversation would be more indicative of dementia.

Katie Puckering, Head of Alzheimer’s Research UK’s Information Services team, previously told The Sun: “We quite commonly as humans put our car keys somewhere out of the ordinary and it takes longer for us to find them.

“As you get older, it takes longer for you to recall, or you really have to think; What was I doing? Where was I? What distracted me? Was it that I had to let the dog out? And then you find the keys by the back door.

“That process of retrieving the information is just a bit slower in people as they age.

“In dementia, someone may not be able to recall that information and what they did when they came into the house.

“What may also happen is they might put it somewhere it really doesn’t belong. For example, rather than putting the milk back in the fridge, they put the kettle in the fridge.”

“I’d only ever written work reports before, so this was a real change of direction for me,” he said.

“I just hope the book sparks conversations. It’s so important to be open about dementia.

“Holding the book in my hand for the first time was quite a surreal experience.

“It was a special moment. I just hope that people read it and that it helps them.

“I want people living with dementia to know that it’s not the end.

“It might feel like it is, but it’s not.

“I have a few problems, I struggle with a few things, but I’m still me.”

Gemma Gray, an involvement and engagement facilitator who works with Michael on projects within the Trust, said: “Michael is a well-respected member of our participation group in Tees.

“He uses his experience to continuously help others and our services.

“We are very grateful for all that he has done, and his book is testament to the person he is – an inspiration.”

Lifestyle hacks to ward off dementia

WHILE there is currently no cure for dementia, lifestyle changes can help ward off some of the symptoms.

Dr Marilyn Glenville, from Natural Health Practice, identified seven of the best.

- Diet (studies have previously shown that the Mediterranean diet – rich in fresh fruit and vegetables, olive oil and oily fish – is linked to a reduced incidence of cognitive decline)

- Vitamins and nutrients (fish oil supplements contain DHA, one of the major omega 3 fatty acids in the brain, which has been found to have a protective effect against Alzheimer’s)

- Sleep (research has shown that people who get less than five hours of sleep each night have double the risk of developing dementia)

- Exercise (an eight-year study found people who were the most active had a 30 per cent lower risk of memory and cognitive decline – and walking distance is more important than speed)

- Brain training (doing crosswords has been found to be beneficial in delaying memory decline by 2.5 years)

- Over-the-counter medicines (cold and flu, heartburn, and sleep remedies contain anticholinergics, which have been linked to brain shrinkage and poor memory performance on tests)

- Health checks (tests can look for metals such as mercury and aluminium, which can be toxic to your brain, as well as checking for nutritional deficiencies and homocysteine levels, which have been linked to a greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s)

Around 900,000 Brits have dementia, with Alzheimer’s responsible for two in three cases. It is the UK’s top killer.

Cases are on the rise, with still no hope of a cure as current medications can only reduce symptoms.

The majority of dementia is not inherited, according to Alzheimer’s UK.

But in rarer types of dementia, there may be a strong genetic link.

This is more commonly the case in young-onset dementia – when the condition is developed before the age of 60.

In these cases, the condition is much more likely to have been caused by a faulty gene being passed down from parents to children,” the charity says.

“In general, the earlier a person develops Alzheimer’s disease, the greater the chance that it is due to a faulty inherited gene.

“So in the really rare cases of a person developing Alzheimer’s disease in their 30s and 40s, it’s almost always because of a faulty gene.”

The most important risk factor for Alzheimer’s is age.

“Because Alzheimer’s disease is so common in people in their late 70s and 80s, having a parent or grandparent with Alzheimer’s disease at this age does not change your risk compared to the rest of the population,” the charity adds.