Amid fierce debates around abortion and challenges with access to healthcare, women in the United States face another battle: the increasing risk of death associated with pregnancy.

The US has the highest maternal mortality rate of all high-income countries, at 22 deaths per 100,000 live births, according to analysis published by the Commonwealth Fund in June. It based this assessment on data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as well as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), of which the US is a member.

Some studies suggest that the high rate of US maternal mortality can be attributed to specific shortcomings in the country’s healthcare system, including one that especially impacts women from minority groups.

So what does the US maternal mortality crisis look like? Is there a way forward? And will abortion bans make it worse?

What is maternal mortality?

Maternal mortality refers to the death of a woman during pregnancy, childbirth or within the “postpartum” period following childbirth or the termination of a pregnancy due to complications or an abortion. These deaths can be caused by conditions such as excessive bleeding or seizures, but are related to or aggravated by pregnancy.

The US count includes deaths that occur within up to a year of delivery or termination of a pregnancy. In total, 817 US women in the US died of maternity-related causes in 2022. The country’s maternal mortality ratio that year stood at 22 deaths for every 100,000 live births.

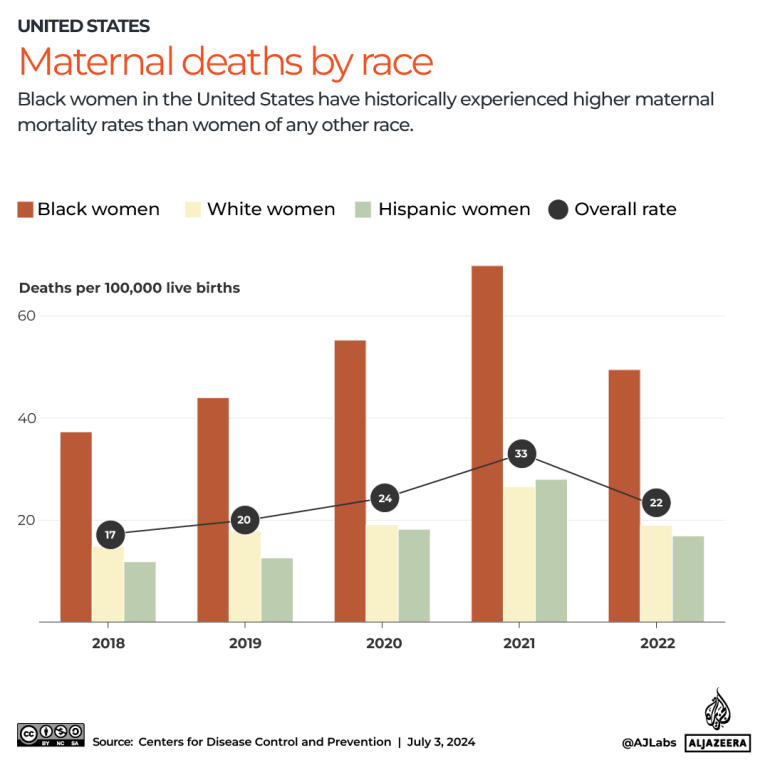

However, this rate varies depending on ethnicity. Black women are more than twice as likely to experience a pregnancy-related death compared to the country’s average. For every 100,000 live births among Black women in 2022, nearly 50 women died within a year of delivery or termination.

What is causing high maternal mortality in the US?

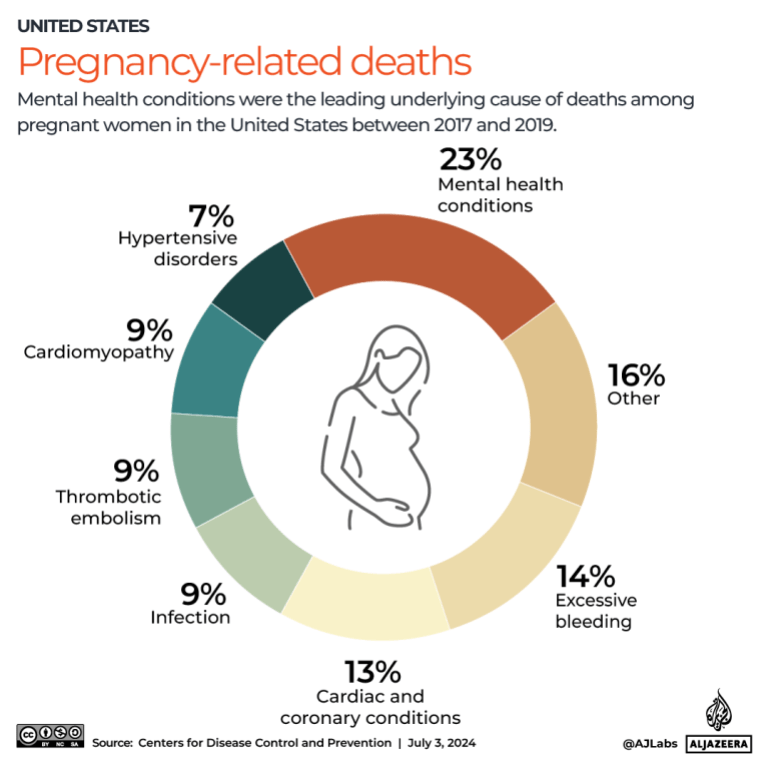

Typically, some of the leading complications associated with maternal deaths have been “obstetric” or directly associated with pregnancy, such as excessive bleeding, placental blockages in the birth canal, and seizures.

However, the type of risks facing pregnant women in the US seem to be changing.

“Over the last two decades, we’re seeing a shift away from the more traditional obstetric risk for dying,” said Alison Gemmill, assistant professor in the department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health at John Hopkins University in the US.

“Now what we’re seeing is that most of the maternal deaths have some kind of underlying cardiovascular condition attached,” she said.

Additionally, a CDC report found that some of the leading causes of maternal death between 2017 and 2019 were mental health and heart conditions (in addition to excessive bleeding).

Pregnancies deemed high-risk from the outset are also becoming more common, according to KS Joseph, a professor at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the University of British Columbia in Canada, who studies maternal mortality around the world. Part of this can be attributed to assisted reproductive technologies such as in vitro fertilisation (IVF), which help women with fertility issues related to factors such as age or pre-existing health conditions to conceive.

Are some ethnic groups affected more than others?

Without universal healthcare, US women – particularly those who are less likely to have health insurance – can lack comprehensive medical support.

Black women are especially at risk. In 2022, for every 100,000 live births, 49.5 Black women died. This was significantly higher than the rates for white (19.0), Hispanic (16.9) and Asian (13.2) women.

This disparity starts with a history of inadequate or inaccessible healthcare, and extends to implicit bias that affects the quality of medical care women receive during pregnancy, according to Melva Craft-Blacksheare, who was an assistant professor at the University of Michigan’s Flint campus until her retirement this year.

“A lot of this [bias] was part of the beginnings of gynaecology, like the idea that Black people don’t feel pain, because OBGYN [obstetrics and gynaecology], started with Dr Marion Sims, the father of OBGYN, working without anaesthesia on Black enslaved women,” she said.

After perfecting his surgical techniques on Black women without anaesthesia, American physician James Marion Sims performed the same procedures on white women who were sedated.

While anaesthesia was not fully integrated into medical practice in the 19th century, several sources have supported the notion that Sims’s decision to not use any kind of numbing technique on Black people was based on the misguided notion that they did not experience pain like white people did.

Craft-Blacksheare added that these misconceptions have been passed down through medical education and training in some form; as a result, Black women often find their concerns being dismissed by medical professionals.

Campaigners and family members believe this was the case in 2016 when 39-year-old Kira Johnson died in a Los Angeles hospital. Johnson, who was scheduled to deliver via Caesarean section, complained of severe pain in her abdomen for 10 hours before being attended to by the medical team. In emergency surgery, after which she died, doctors found that Johnson had been bleeding internally and had three litres of blood in her abdomen.

Research also shows that the chronic stress of experiencing racism can lead to accelerated aging and poorer health outcomes for Black women, putting them at higher risk of conditions like hypertension and pre-eclampsia, a potentially deadly condition if it is not identified, during pregnancy.

Craft-Blacksheare said that social challenges like poverty and domestic abuse, which Black women in the US often face at higher rates than other groups, should be considered by providers when treating pregnant women, as these factors can impact their health or ability to attend appointments.

Is the way the US monitors maternal mortality to blame?

The US method for recording pregnancy-related deaths is highly debated, and has raised concerns that it obscures the underlying causes of death in some cases.

In 2003, states across the country began adopting a death certificate that included a “pregnancy checkbox”, asking if the deceased was pregnant at the time of death or within the previous year. By 2017, when all states adopted the checkbox, the maternal mortality rate had more than doubled.

The CDC claims this checkbox addressed previous underestimations, but critics argue it is frequently ticked incorrectly, resulting in an overestimation of the number of deaths.

For example, one of the CDC’s own assessments found that in 2013, the checkbox was marked for 147 deceased women above the age of 85. Such findings have resulted in new rules for the checkbox, such as limiting its application to an age range of 10 to 44.

However, experts argue that ticking the checkbox still connects a significant number of deaths to pregnancy, even when that may not have aggravated the person’s demise.

“This overestimation and this lack of specificity with regard to causes of death is hurting the system and we are not able to identify what it is that we need to go after if we want to prevent these deaths,” explained Joseph, pointing to data showing that between 60 to 80 percent of maternal deaths in the US are preventable.

He added that if death certificates clearly outlined how being pregnant played a role, this could help accurately identify and address those preventable or common risk factors associated with pregnancy.

Craft-Blacksheare, who is on Michigan’s maternal mortality review committee, said she believes that the US maternal mortality cases are correct and not overestimated, however.

She explained that the committee not only confirms whether pregnancy was an aggravating factor in the death, but assesses additional factors such as whether the death was preventable or discrimination was involved in care.

Gemmill said that while state-level committees are important, the US needs to invest more in federal infrastructure to investigate the reliability and validity of maternal death reporting – similar to other high-income countries.

“We’ve lagged because we don’t have that kind of national system, that kind of gold standard system,” she said.

What else can be done to improve outcomes for mothers in the US?

Provide better prenatal care

Several key stages of pregnancy require special attention to reduce maternal mortality, experts say. These include medical assessments prior to conception, prenatal care during pregnancy, home visits and regular checkups following delivery.

About one in seven US babies were born to a mother receiving inadequate prenatal care in 2022, according to a study by the March of Dimes, a non-profit organisation dedicated to preventing premature births and birth defects.

Gemmill said that many women do not get treated for underlying conditions such as prediabetes until it is observed in pregnancy-related scans, causing them to miss out on opportunities for early intervention.

Improve postpartum care and expand maternity leave

Data indicates that women’s health is especially neglected in the postpartum period. Sixty-five percent of maternal deaths occur postpartum, with 30 percent occurring between 43 to 365 days after delivery.

Additionally, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, up to 40 percent of women do not attend a postpartum visit, potentially missing opportunities for timely intervention for health risks.

The Commonwealth Fund report also found that an absence of federally mandated paid maternity leave gives women less time to “better manage the physiological and psychological demands of motherhood”.

Overall, experts say that pregnant women need more focused care in clinical settings. “There’s so much emphasis on saving infants’ lives and making sure that infants are healthy. But then that means that the mom is an afterthought in many ways,” said Gemmill.

Focus more on maternal needs and midwifery

Craft-Blacksheare also sees healthcare for pregnant women as an infrastructure issue. “It’s driven by physicians, it’s driven by hospitals and it’s not driven by maternal needs,” she said.

Some suggest that increasing access to midwives can help make maternal healthcare more holistic. This could also compensate for a shortage of obstetricians and gynaecologists in the US, according to the Commonwealth Fund report.

Midwives are health professionals trained to medically and emotionally support women during pregnancy, labour and the postpartum period.

“Midwifery care is a very specialised care that puts the woman and the family in the centre of their care”, says Craft-Blacksheare, adding that midwives should work together with physicians, especially in high-risk situations.

Will US abortion bans make maternal mortality worse?

A study published in the journal Women’s Health Issues by researchers in Boston suggests that abortion bans, several of which have been passed in the US in the past year, will exacerbate maternal mortality, particularly when it comes to racial inequalities in deaths.

When local abortion facilities are unavailable, pregnant women are often forced to travel to other cities, counties or states for the procedure. Black and low-income patients, who frequently already have children, are disproportionately affected and often lack the economic security, social support, and childcare resources needed to take time off work and travel for an abortion.

When women are already at risk of dying due to a pregnancy complication, abortion restrictions force them to carry through with the pregnancy against their will. Once again, the effects of this are expected to be felt most deeply by Black and Hispanic women who lack access to comprehensive healthcare, according to the study.

The bans may also put the US even further behind other high-income countries, which largely allow abortions, in terms of maternal mortality rates.

Gemmill, who is also studying the effect of the abortion restrictions, said that while data is not currently available to draw a conclusion, an increase in maternal complications is possible.

“We’re already seeing stories come out from certain states where people aren’t getting the care that they need and it’s putting their lives at risk,” she said. “So I definitely think we will be seeing an increase because of that.”