Perhaps improbable for a bustling Latin American metropolis, one of the most well-known tourist attractions in the Argentinian capital of Buenos Aires is a graveyard.

The Recoleta Cemetery includes a maze of Art Nouveau and neo-Gothic marble mausoleums, the tomb of lionised former first lady Eva Peron – and a show-stealing colony of cats. For decades, tourist cameras strayed from the wrought-iron doors and sculpted Madonnas that decorate the graveyard’s sumptuous mausoleums and instead trailed the cats as they sauntered and sunbathed. The stray cats were the subject of a 2016 documentary. They were even recently brought up on the media tour of the latest Mad Max film, Furiosa, thanks to a nostalgic comment from the Argentina-raised movie star Anya Taylor-Joy.

The cemetery looms so large in visitors’ itineraries because of its architectural extravagance and its connection to the country’s elite. Nestled inside one of Buenos Aires’s poshest neighbourhoods, it’s the burial place of past presidents and assorted national heroes – a who’s who of Argentinian history, the necropolis edition. For as long as most locals can remember, the cats topped off the site’s grandeur with a touch of whimsy.

Sergio Capurso, a tour guide at the Recoleta Cemetery and the son of a former funeral services employee, said the place was “full of cats” in his first visits as a young child in the late 1970s. He has since seen scores of visitors fall for them during his tours.

One of those besotted tourists was Blake Kuhre, a visitor from the United States who would go on to create the Guardians of Recoleta documentary. Kuhre remembers that coming across “a top tourist attraction that was literally swarming with cats felt completely foreign. … You have this form of life that’s living in a place where everyone has gone to rest.”

![The six remaining cats in the Recoleta Cemetery wait for the arrival of Marcelo Pisani, 55, a local florist who has taken over the care of the cats, in Buenos Aires, Argentina on July 1, 2024. -Once home to a colony of more than 60 stray cats, the famed Recoleta Cemetery now houses only six cats: Lili, Princesa, Llorona, Lucio, Cabezón and Grisecito. Pisani, the florist, visits the cemetery every day at 5am to feed the cats. However, in a country with an ever growing economic crisis and 200% inflation, he is finding the cost of looking after the animals increasingly prohibitive and has become reliant on donations from visitors. [Maria Amasanti / Al Jazeera]](https://www.occasionaldigest.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/MAmasanti_AlJazeera_RecoletaCats_03-lighter-1721491637.jpg)

But things have changed.

In 2024, the thousands of visitors who stream through the peristyle at the entrance of the cemetery will struggle to spot the Recoleta felines. Their population went down from an estimated peak of more than 60 decades ago to just half a dozen today. That’s due to a recent and sometimes contentious adoption drive.

To cat welfare advocates, the new whiskers-less look of the Recoleta Cemetery is a sign of progress. No amount of fame and folklore, they say, makes up for the fact that stray cats have significantly shorter lifespans than those with indoor homes. But others lament that something was lost as more and more cats were moved away from the cemetery, taking some of the tourism hotspot’s mysticism with them.

“It was one of the things that people used to always expect as part of a visit to the Recoleta Cemetery,” said Robert Wright, a guide who worked for the well-known American travel writer Rick Steves for more than 20 years and who led tours in Recoleta from 2003 to 2015.

As communities from New York and California to France and New Zealand struggle to humanely contain surging populations of stray cats, Recoleta may not present much of a blueprint. The visibility that made the Recoleta cats so popular among cemetery-goers went a long way in helping them find adopted homes – some as far away as the US. But the story of Recoleta and the unravelling of a uniquely beloved stray cat colony could help more and more people see through the often misleading charm of urban fauna.

“People had this emotional, cultural attachment [to the cats]. And we try to explain to them that, actually, it’s a good thing that there are fewer cats around,” said Victoria Bembibre of Hace Feliz A Un Gato, a cat welfare group that looks after stray cats mostly at another Buenos Aires tourist attraction, the nearby botanical garden.

![Marcelo Pisani feeds Arturito, a stray cat from outside the cemetery who visits daily at 5 a.m. to benefit from Pisani's feedings, in the entrance hall of Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires, Argentina. on July 1, 2024.-Once home to a colony of more than 60 stray cats, the famed Recoleta Cemetery now houses only six cats: Lili, Princesa, Llorona, Lucio, Cabezón and Grisecito. Marcelo Pisani, the florist, visits the cemetery every day at 5am to feed the cats. However, in a country with an ever growing economic crisis and 200% inflation, he is finding the cost of looking after the animals increasingly prohibitive and has become reliant on donations from visitors. [Maria Amasanti / Al Jazeera]](https://www.occasionaldigest.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/MAmasanti_AlJazeera_RecoletaCats_22-1721493697.jpg)

Each of the places where outdoor cats cluster comes with its own set of hazards. Unlike most cemeteries, vegetation is scarce at the hyper-urban Recoleta. That means less shade for its cats and a high rate of cancers linked to sun exposure. And while most of the cemetery’s fancy mausoleums are well-maintained, a few have fallen into disrepair with broken glass leaving coffins exposed. Locals said some of the cats would sometimes fall into underground crypts and struggle to get out.

“In the past, I also may have thought, ‘Oh, how nice to see cats around.’ But that was when I didn’t understand how crude the reality is for any cat that lives outside,” Bembibre said.

The remaining Recoleta cats now mostly come out early in the morning and in the evening when the cemetery isn’t as crowded. They have become less accustomed to being around people since the cemetery’s pandemic closure – Argentina had one of the world’s longest COVID-19 lockdowns.

The cats’ current caretaker is Marcelo Pisani, 55, an animal-loving florist who runs a flower stand near Recoleta. He is allowed into the cemetery before it opens to tourists every day, usually about 5:30am, to put out food bowls.

“I take this very seriously, this matter with the cats. I’m always here for them. I never go out of town, not for Christmas, not for New Year’s,” he said. “And it doesn’t bother me. I dedicate my life to them.”

‘There was a lot of tension’

Stray animals are a fixture of daily life across Latin American cities – sometimes to the surprise of international visitors. That’s partly because municipalities in the region play a minimal role in animal control and don’t typically fund public shelters. When locals want to let go of their pets, many have historically taken them to spots like the cemetery or the botanical garden. If those pets aren’t fixed, their population quickly swells.

In Buenos Aires, the Recoleta Cemetery cats were the face of a top tourist attraction, but their wellbeing always relied on the love and largesse of locals like Pisani.

Starting in the 1990s, a wealthy neighbourhood widow whose husband was interred in the cemetery took up the cats’ cause. She paid for daily feedings and regular flea treatments. Alongside cemetery management, the widow, Alicia Farias, resisted efforts to move the cats into adopted homes.

“There was a lot of tension. … They were afraid of losing the cats because they were part of the business. Tourists loved them,” said Alejandro Aranda Rickert, a local sculptor and painter who visited the cemetery every Sunday to sketch. Although Aranda Rickert enjoyed capturing the cemetery cats in drawings – his work was featured in a video about “cat-crazy artists” on a popular art history YouTube channel – he made increasingly vocal pleas that the cats be adopted.

“I didn’t want to cause problems. I just wanted for the cats to be better off,” he said. “Cats love to be warm. In the cemetery, there wasn’t even a blanket for them. That place is all stone, marble and bronze.”

Shortly before the pandemic, Farias died, and the cats’ wellbeing cratered. That brought momentum to those who’d been advocating for adoptions. With the help of other volunteers, Aranda Rickert created a social media campaign to connect cats with locals willing to care for them. Having gotten wind that the cats were being adopted, some cemetery visitors also took some home, bypassing Aranda Rickert and his group.

“I had to fight at first. It wasn’t something that was always nice. But what was nice was seeing that I could help the cats,” he said.

Carmen Marconi was one of the locals who adopted a cat – in her case, a then-11-year-old grey male, whom she named Senor.

Initially, she worried she hadn’t done right by him.

“When I first took him from the cemetery, I felt bad because I lived in a tiny apartment. I thought, ‘Poor cat. He was free and now he lives in a rectangle,’ you know? But the truth is, it ended up being good for him. Otherwise, he wouldn’t have lived as long.”

Shortly after bringing Senor home, Marconi took him to a veterinarian who found him to be severely dehydrated and diagnosed an ear disorder and toxoplasmosis, an infectious disease. After several rounds of treatment, his condition improved. He is now still alive at 17.

“You walk through the cemetery and you see the cats sitting in the sun, and you can’t imagine how rough they actually have it. At least I didn’t realise it until I took this cat home and saw the state he was in,” Marconi said. “People romanticise the idea of the stray cats who are fed and taken care of by the neighbourhood and they seem healthy enough and tourists like them. And that’s not a good thing. They’re not just another gargoyle on a tombstone. They’re living beings.”

Bembibre compared private citizens organising to reduce stray animal populations to overwhelmed firefighters struggling to contain an out-of-control fire. She said the wellbeing of street animals in a city like Buenos Aires won’t improve in a significant way until the city government gets involved. And as more than 250 percent inflation continues to empty Argentinians’ pocketbooks, she worries fewer and fewer pet owners will want to bear the cost of fixing their cats and dogs, which could result in more strays.

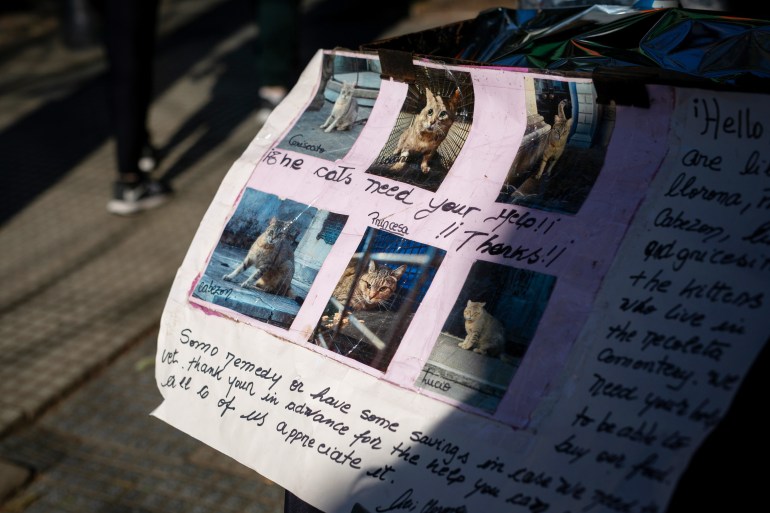

At the Recoleta Cemetery, Pisani relies on donations from tourists to pay for the remaining cats’ food and any medication they might need. Whenever new cats are abandoned at the cemetery, Pisani and others swiftly move to adopt them into a new home. The six Recoleta cats who are left, all of which have been fixed, will be the last of their kind.

“There’s going to come a moment where the Recoleta Cemetery will no longer have any cats,” he said. “That will be incredible.”