Nicholas Dames remembers the first time he really got thinking about a very obvious but largely invisible writing device.

It was around two decades ago, when he was completing a PhD in English and American literature.

“A friend of mine, who was not an academic, over drinks one night, just blurted out to me, ‘why do novels have chapters?’,” the Columbia University humanities professor tells ABC RN’s Late Night Live.

“I realised I hadn’t the faintest clue how to answer that question. It was one of those, ‘why is the sky blue’ questions.”

In the years that followed, Professor Dames returned to this question again and again, so he decided to explore the history of the chapter.

The topic may sound deeply academic, but it’s not all laborious details about medieval tomes.

At the heart of this history is how we tell stories.

And from a child’s development to an evening on the couch watching Netflix, the chapter affects our lives in many unnoticed ways.

Chapter 1: A long history

For much of human history, texts were not divided into sections. They were words upon words upon words.

The earliest chaptered text that Professor Dames found was a Roman legal tablet from Urbino, dating back to the second century BCE.

The tablet was announcing a new law, explains Professor Dames, who’s written the book The Chapter: A Segmented History from Antiquity to the 21st Century.

“It was a continuous law, but the law was segmented and those segments had brief titles,” he says.

This is how early chapters were used — to organise informational texts on topics like law, medicine or language, to “tell readers where to look for the information they were seeking”.

For much of antiquity, the most common type of text was the scroll. And these sometimes came with a chapter list, in an accompanying, smaller scroll.

Chapter 2: Different ways of writing

Professor Dames’ research considered two millennia of Western literary history, which meant he also saw how the written word has evolved.

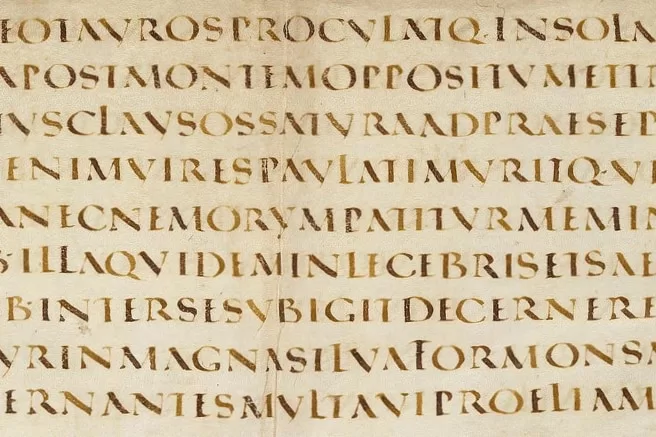

Today’s reader would likely find ancient texts totally unrecognisable.

For example, up until the ninth century, written lines were continuous chains of letters with no breaks between the words.

“To try to get one’s mind around how one read without the separation of words, it’s a truly tricky task, but they seem to have done it without much difficulty,” Professor Dames says.

His research shows that “the history of text is a history of ways in which we segment text”.

“We currently live in a regime where text is very elaborately segmented, but that wouldn’t have been the case 2,000 years ago,” he says.

Chapter 3: Making a living by making chapters

Over much of its history, chaptering was not the responsibility of writers, but of editors.

This was called “capitulation”.

“It was an ancient technique, and that extends well into medieval Europe, for taking a text that you have not written, a text that pre-exists you and …. dividing it in a way that makes sense,” Professor Dames explains.

“It was an intellectual labour that was performed by scholars, particularly within the Roman Empire [and also] by medieval monks. It was a very, very long-lasting form of intellectual labour.”

Depending on the individual editor, a book could be divided up in countless different ways.

Chapter 4: Dividing the Bible

Professor Dames says perhaps the “most visceral” chapter in the history of chapters is the Christian Gospels.

The Gospels were originally written without chapters, he explains.

But over the years, mainly between the fourth century and the 13th century, they were divided up in innumerable ways.

Some scholars chopped up the Gospels into extremely tiny chapters, others into larger ones.

It got confusing. For example, chapter 12 in the Gospel of John could mean one thing in one version and a very different thing in another.

This changed in the early 13th century.

Although unconfirmed, it’s thought that Stephen Langton, a theologian at the University of Paris, who later became the Archbishop of Canterbury, came up with today’s Gospel chapters around 1210-1220.

Another theory is that this chaptering system came from a series of religious institutions in England at this time.

The idea was to create chapters that were roughly of equivalent size, but that also made sense in the narrative.

But this form of chapters was “greeted with a bit of scepticism at the time … and continued to be greeted with scepticism well into the 18th century”, Professor Dames says.

Chapter 5: Anti-chapters

Not everyone was thrilled that chapters were standard parts of texts.

In the 17th century, English philosopher John Locke was a critic of Bible chapters. In fact, he thought it shouldn’t have been done at all, Professor Dames says.

“He thought that the chapter break disturbs the progression of thought as you read.

“[Locke believed] one should read in an uninterrupted fashion, following what he called a chain of argument from start to finish, and chapters were a disastrous way to address the text.”

Chapter 6: Marking time

Next up is a big shift: The use of chapters moved into the realm of the writers themselves.

Chapters became part of the author’s writing process, and stories were written with chapters in mind.

As the modern novel emerged in 17th and 18th century Europe, chapters served as timing devices, part of a story’s rhythm.

“Authors made the decisions — to cut chapters short, or to sculpt them in certain ways,” Professor Dames says.

Chapters became “a really wonderful place for authors, or one could say narrators, to directly address the reader”.

“To remind the reader of their ability to leave or to take a break. To solicit the reader’s attention. To apologise for taking too much of the reader’s time. To establish a kind of communicative relation with the reader.”

Chapter 7: Chapters in children’s development

Professor Dames says that today, one marker of a child’s development is the transition from picture books to “chapter books”.

Chapter books are “a big developmental step in the experience of children with narrative … [they are] what children read when they are first really maturing into literacy”.

This transition is analogous with “what psychologists call ‘object permanence’ — the moment in infancy when a child realises that just because you’ve hidden an object, it still exists”.

“A chapter works that way, in terms of time, for children,” he says.

“It says that just because the story has paused, you can resume it … It tells children that they are allowed to leave and re-enter narratives.”

Chapter 8: Streaming

Technological developments over recent decades have seen the idea of chapters cross over into other ways of storytelling.

Read more from Late Night Live

Chapters have become part of long-form TV or streaming shows, with episodes carefully curated into various segments, often using reintroductions and cliffhangers.

“It means that these narratives can sort of filter into our lives … when we aren’t consuming fiction, we can let the experience diffuse into our day,” he says.

For example, this year’s FX series Shōgun started each episode with a written title, and then the drama unfolded in a fairly self-contained way.

Chapters are “so common and so flexible, and so unformalised that they can always be reinvented,” Professor Dames says.

“So I think that in some sense, [chapters] are always going to be with us.”

RN in your inbox

Get more stories that go beyond the news cycle with our weekly newsletter.