There is nothing remarkable about that. In this year alone nearly 50 percent of the world’s population will head to the polls in at least 64 countries. They may not all meet the bar of being free and fair but that is still some four billion people who will fill in a ballot in some form or another.

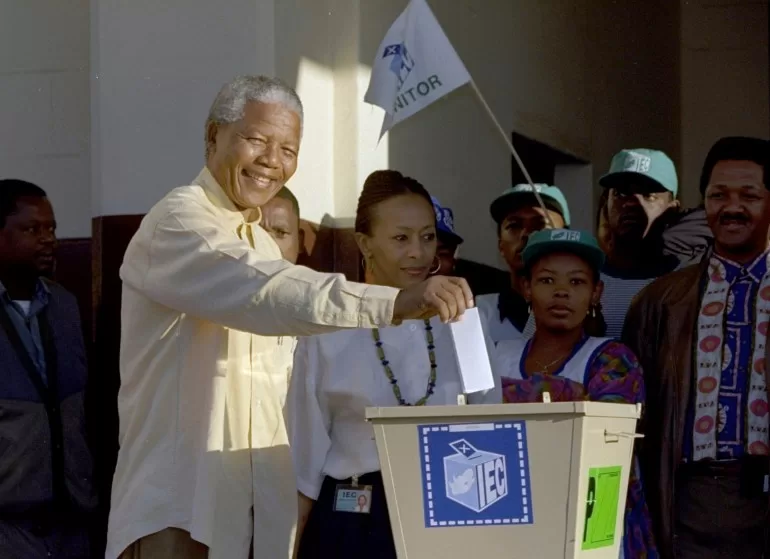

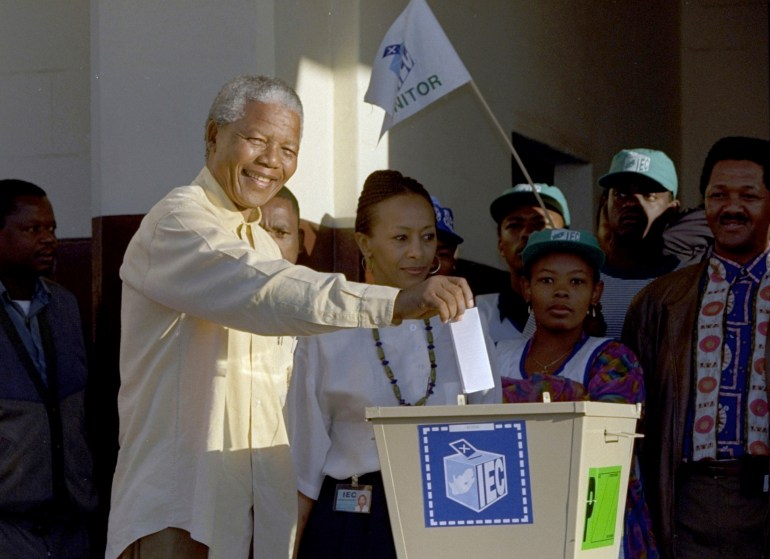

But this particular vote was cast 30 years ago on April 27, 1994. It was South Africa’s first democratic election and the man voting for the first time was Nelson Mandela.

He chose to vote in Inanda in KwaZulu-Natal – the polling station close to the grave of John Dube who was the founding president of Mandela’s African National Congress (ANC). Being Mandela, he stopped to pay his respects at the graveside, and then being Mandela he waited his turn to vote rather than go straight to the front.

I’d joined the queue shortly before him to be in place when he voted – and I, along with about 20 million other South Africans, cast a ballot for the first time. The vast majority had been forbidden from voting in the apartheid state because they were not white. In my case, I had chosen not to exercise the right to vote until everyone who wanted to could – a white-only vote was one, I believed, in support of a white-only state.

The polling booth was moved outside into the gentle April sunlight – and I stood a few feet away as Mandela held his ballot aloft. He moved from one side of the ballot box to the other, checking the media was happy with the angle, and then with that incandescent smile he cast his vote. Onlookers erupted in a refrain that I’d heard at so many protest meetings through the dark apartheid years: “Viva Mandela, viva, viva the ANC, viva.”

He shuffled forward to where some microphones had been positioned, the smile fading as he acknowledged the import of what had just happened in a simple sentence: “It is the realisation of hopes and dreams that we have cherished over decades.”

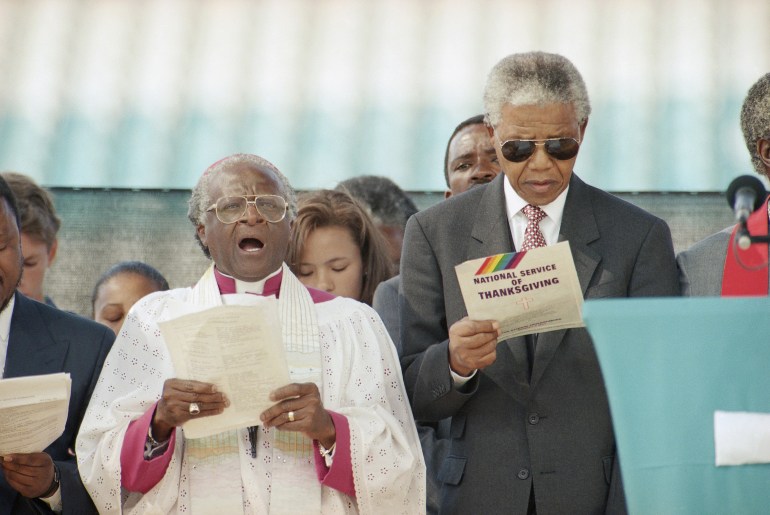

Although Mandela voted on April 27, a day that has now become Freedom Day, the process was held over a three-day period throughout the country. Jubilant people of all colours stood in long queues, sometimes for hours, it was a time of celebration, a time in which South Africa truly became the Rainbow Nation. The mood was summed up most succinctly by a self-professed card sharp who’d come to South Africa from neighbouring Lesotho decades before – jumping up and down after casting his vote in Cape Town, Archbishop Desmond Tutu giggled maniacally and repeated time and again: “Free at last, we’re free at last.”

Civil war avoided

Amid the joy though, it was hard not to reflect on how close the country had come to outright civil war in the months preceding this election.

Political violence was ever-present during the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA) lengthy negotiations held to secure agreement of all parties on the nature of a new South African democracy.

At one stage I watched as Mandela pulled apartheid President FW de Klerk into an annexe out of earshot – the normally equanimous ANC leader was gesticulating violently, clearly enraged, while de Klerk stood dumbly, looking at the ground for the most part.

Later I learned that Mandela had been briefed that National Party (NP) leader de Klerk was suspected of still deploying armed groups to foment violence in a bid to either disrupt negotiations or gain more leverage in them. “He accused de Klerk of switching violence on and off like a tap, and threatened to walk away if it didn’t stop,” one of Mandela’s senior aides told me.

Then there was the issue of Mangosuthu Buthelezi and his Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) – the Zulu-based movement refused to take part in negotiations and continued deploying fighters to attack political opponents in several parts of the country, the Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal in particular. Mandela met Buthelezi in Durban at the beginning of March 1994 and attempted to secure both a truce and an agreement to end the violence. He implored the Zulu leader to call off his “impis”, or armies, and join the electoral process.

I stood in the foyer of the Blue Waters hotel and watched as Mandela left the meeting, his face set in a grim mask, clearly having failed. An Inkatha adviser told me Buthelezi was insisting on the autonomy of the Zulu tribe, and of the Zulu monarch Goodwill Zwelithini. Part of the problem, too, was Buthelezi’s belief that as a Xhosa, Mandela was seeking primacy of his own tribe. This despite the core principle of both Mandela and his ANC that tribe and race should play no part in political affairs.

A few days later the ANC sent a new delegation which met with Buthelezi in private. It was led by Mosiuoa Lekota, known as “Terror” because of his youthful skills as a soccer player. Terror was part of a new generation of activists who had been imprisoned on Robben Island alongside Mandela and other leaders. He entered prison as a Black Consciousness follower opposed to the nonracial ANC but was converted to the ANC cause while in prison. On being released he became a powerful force in the United Democratic Front (UDF), a body that was formed to fill the public political vacuum left because of the apartheid government banning the ANC. I’d become friends with Terror, and in fact gave evidence for the defence when he and other UDF members were tried and convicted in the Delmas Treason Trial. Terror was sent back to jail, but released with all other political prisoners when the ANC was unbanned in 1990.

Most importantly, though, with regard to Buthelezi, Terror was from the small Orange Free State town of Kroonstad and was neither Xhosa nor Zulu. While on Robben Island he’d also forged a close relationship with Jacob Zuma, who as a Zulu had the ear of Buthelezi. (It was a relationship that ran into rocky waters in a new century but more on that later).

Terror struck a deal. He told me subsequently that Mandela and other senior ANC leaders had put together a proposal they knew Buthelezi couldn’t resist if it came from what he would see as a messenger untainted by tribe. Buthelezi was promised a seat in the Government of National Unity for the first 10 years of democracy, and the status of Zulu royalty would be guaranteed in the constitution.

Buthelezi agreed to take part in the election – a decision that came so late that the name of the IFP had to be pasted at the bottom of the ballot sheet shortly before the polling began on April 26, 1994. There was a marked cessation in violence, and the election went ahead peacefully.

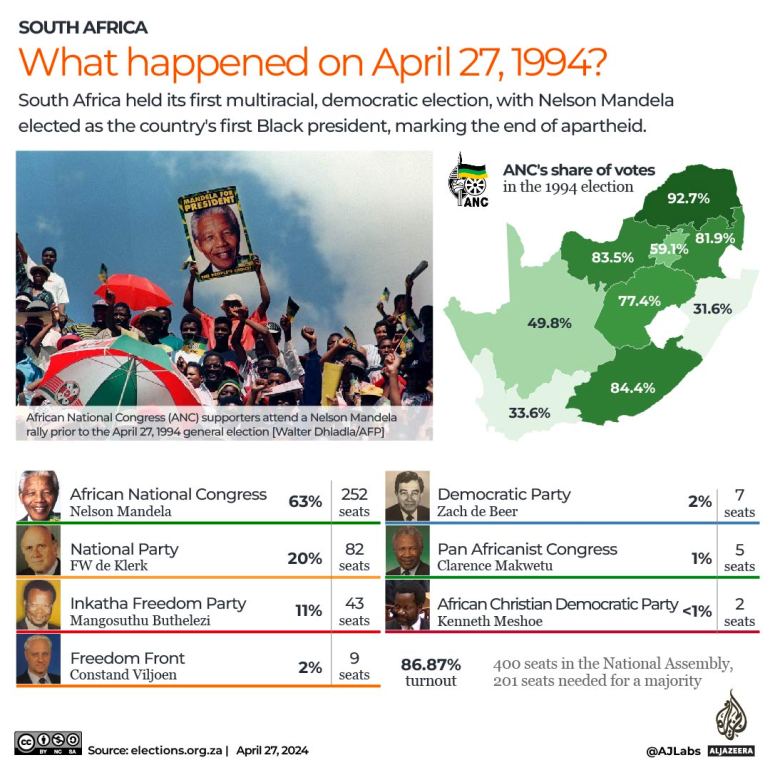

The reason why Mandela voted in the Zulu stronghold of Inanda was to send a powerful message that the killing would be no more. The IFP won 11 percent of the vote, de Klerk’s NP 20 percent, and the ANC emerged victorious with 63 percent.

The nation celebrated, as it did the following year when South Africa won the Rugby World Cup, and in 1996 when it won the Africa Cup of Nations becoming the continent’s football champions. A beaming Mandela handed over the trophy on each occasion.

It would be decades before national unity would be so publicly celebrated again.

‘The ANC is dying’

South Africa won the Rugby World Cup again in England in 2007, and this time it was Mandela’s successor, Thabo Mbeki, who appeared with the team. The joy back home was muted though in what had become a political crisis of massive proportions.

It all began to fall apart in 2005, when then-President Thabo Mbeki tried to get rid of his Vice President Jacob Zuma, who was facing charges of corruption and rape. After years of political infighting that began to rupture the ANC, Zuma was elected the organisation’s president at its National Convention in Polokwane in 2008. Despite pleas by Mandela to end the infighting it was the first time in nearly 60 years that the ANC leadership was contested.

Mandela’s old comrades were rooted out of their positions by the Zuma loyalists – among them was Terror Lekota who’d been serving as the ANC’s secretary-general. I spoke to Terror in Polokwane straight after he’d been voted out of his position.

“It’s over,” he said. “The ANC is dying. Belief in nation has been lost in belief in faction and self-interest. The giants of the past have been replaced by maggots whose concerns are not country, but self.”

Terror left the ANC and formed his own political party. In 2008, Mbeki stepped down as the country’s president at the request of the ruling ANC – and was replaced by Zuma.

Zuma ruled over a country in decline – rampant corruption, economic mismanagement and sheer greed saw a giant on the continent shrivel to a skeleton of its former self.

Mandela died in December 2013, and the country came together once again, this time not in celebration but in mourning.

His coffin was taken around the country and long lines formed to pass it and pay their respects – an echo of the queues that formed when so many voted for the first time in 1994. His public memorial service was held on a dismal rainy day at a football stadium in Soweto. I walked down to the VIP drop-off point and spoke to some of the many leaders that Mandela had influenced as they arrived – among them members of the Elders, a group of global leaders Mandela had formed in 2007 to work together for peace, justice, human rights and a sustainable planet.

Former US President Jimmy Carter had spent decades observing elections around the planet. “South Africa 1994 was the most special one,” he told me. Another Elder, Desmond Tutu, was smiling; “he’s going to God,” he said, “and can tell him he got me my vote”.

“What about the ANC now?” I asked. Tutu rolled his eyes and said, “Let’s not make the dead angry.”

“I’ll miss him,” said former President de Klerk. “I will too,” said another former president, Mbeki, a few minutes later.

I went back up into the stands in the stadium – there were cheers for both former presidents when they entered; though not as loud as those for the then-US President Barack Obama. Zuma, then president of South Africa, entered to resounding boos.

Another crucial election

Over the years, Zuma faced several corruption charges and finally resigned as president in 2018.

He was subsequently convicted of corruption, sentenced to jail, released on health grounds, resent to jail, and then released because of what was described as overpopulation in prisons.

The real reason, many believe, was an attempt to curb the massive violence being carried out by his followers in protest against his imprisonment.

Zuma’s support base is largely fellow Zulus, an echo of the impis unleashed so many years ago by the IFP’s Buthelezi. On being expelled from the ANC, Zuma formally joined the MK party, or uMkhonto weSizwe (meaning Spear of the Nation), a name taken from the former military wing of the ANC which the governing party has attempted to dispute its claim to. At this stage, though, MK is set to contest the elections in May and could seriously threaten another ANC victory.

Zuma’s successor as ANC president, Cyril Ramaphosa, came to office with the pledge of rooting out all corruption and restoring the nonracial principles and honesty of Mandela’s ANC. It’s a ship he is struggling to steer. But as a man who earned respect as general secretary of the mineworkers union 40 years ago, as a person who was handpicked by Mandela to be at his side when he was released from prison, and seen by many as imbued with the best of what was the ANC, many South Africans are hoping that he will succeed.

Like so many South Africans around the world, I was watching as my country won another Rugby World Cup in 2019. This was a different team to the ones of the past; it was truly representative of the nation it represented and had developed a culture of inclusiveness and humility.

No one embodies what this team is about more than its captain, Siyamthanda “Siya” Kolisi. For the first time since 1994 the country celebrated as one – and Siya and his teammates became symbols of hope for a battered people.

Celebrations again with yet another World Cup win under Kolisi in 2023, this time in France. And a consistent message from the captain – that the everyday hardship for the people at home is the prime motivating factor for his team.

“So many problems for our country, but to have a team like this … we know we come from different backgrounds, different races, and we came together with one goal and wanted to achieve it. I really hope that we’ve done that for South Africa, to show that we can pull together if we want to work together and achieve something.”

Among the celebratory footage I saw were images of people dancing in Kolisi’s hometown of Zwide in the Eastern Cape. It’s an area I know well – throughout the dark and deadly decade of the 1980s, Zwide and its neighbours around the urban centre of Uitenhage were the epicentre of resistance to the apartheid regime. They were, and remain, areas of intense poverty.

For years I reported as countless residents were shot by the police and the army, arrested, tortured, and in some cases simply taken away and executed. But still they fought back. It became a deadly pattern – demonstrations against the regime, people killed by the apartheid forces, then the funerals, more demonstrations, more deaths. There seemed no end to it, no hope, yet the people would not give up.

It became clear to me that what motivated this resistance was more than hope, it was a belief that things would get better. It was a belief that beckoning beyond the ugliness was a nation in which all would be free, a place in which race or tribe or class played no major part, a country in which a vote was a given.

This is where Kolisi comes from, and this hope is what he reminds me of.

The promise made by Nelson Mandela 30 years ago of a better life is still to be fully realised, but Kolisi’s words are a reminder that all is not done, the process may not be over.

“We love you South Africa,” he says, “and we can achieve anything if we work together as one”.