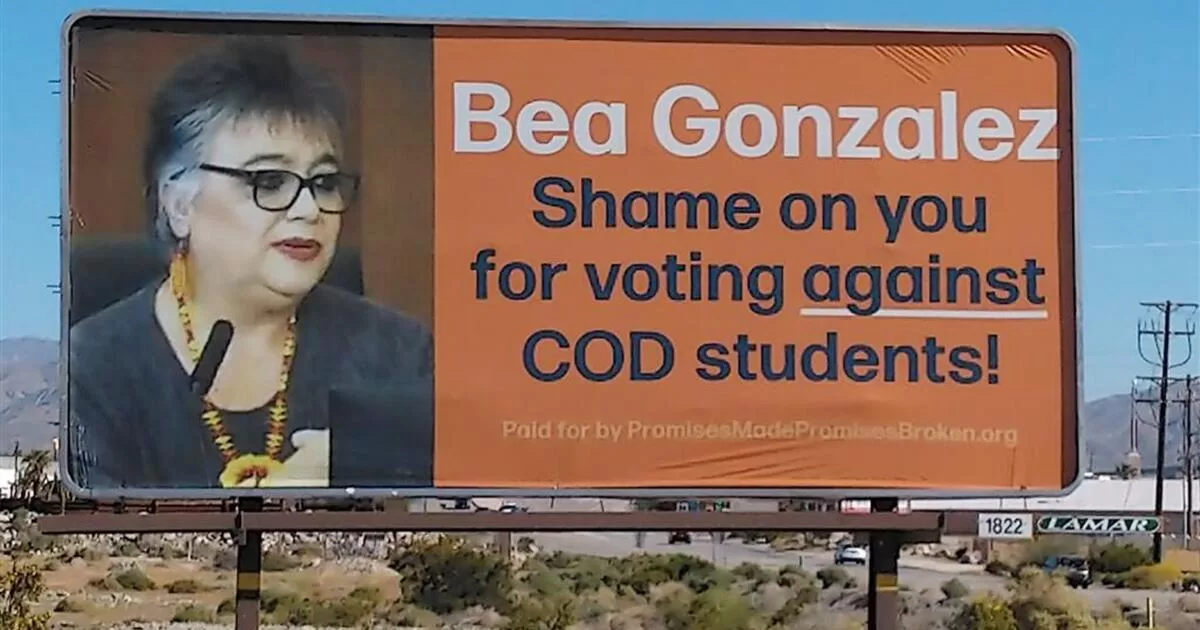

Even in this cluttered landscape, two billboards featuring Desert Community College District Board trustee Bea Gonzalez stand out.

They’re at opposite ends of the valley — one near Fantasy Spring Resort Casino in Indio, another just east of the Indian Canyon Drive exit in Palm Springs — and feature the same photo of the spiky-haired, bespectacled trustee.

“Bea Gonzalez. Shame on you for voting against COD [College of the Desert] students!” the billboards blare against an orange background. Below that is the name of the group that funds them, Promises Made Promises Broken.

The hundreds of thousands of concertgoers who’ll pass by most likely won’t give the billboards a second thought. But they tell a story of a political brawl that has consumed the Coachella Valley.

Supporters say a long-planned College of the Desert campus in downtown Palm Springs, which is expected to break ground this year, will bring prestige and new programs such as hospitality, engineering and film to an area that needs it. Opponents such as Gonzalez say that the estimated $400-million cost is exorbitant and that the funds should be spread across underserved areas of the Coachella Valley.

When Gonzalez beat a two-term incumbent in a 2020 election, she joined two other trustees in trying to limit the scope of the Palm Springs project, if not scuttling it altogether.

Soon came the attacks: An unsuccessful 2021 push for a faculty vote of no confidence against Gonzalez and her trustee allies. A 2022 election that saw former college president and Gonzalez critic Joel Kinnamon join the board and flip the majority to his favor. A threatened recall that never materialized. Whispers that Gonzalez is a puppet of Latino politicians based in the eastern portion of the Coachella Valley who have increasingly clashed over resources with pols in the wealthier, whiter western communities.

And, of course, there are the billboards, which have shifted up and down the 10 since the beginning of 2023. They’ve become such a part of the region’s life that Gonzalez recently told me she’s used to having strangers stare at her before asking if she’s that woman.

“I have to laugh,” the 55-year-old said as we enjoyed bowls of split pea soup at a diner in Desert Hot Springs, “because what else can I do?”

The brawl has grown so contentious that the city of Palm Springs sued College of the Desert in 2022 for failing to turn over documents related to land use decisions, in alleged violation of the California Public Records Act. Kinnamon got into a physical altercation in January with United Food and Commercial Workers Local 1167 President Joe Duffle, a Gonzalez ally, with each accusing the other of starting the fight.

Kinnamon didn’t respond to repeated requests for an interview. Meanwhile, Promises Made Promises Broken — which the Desert Sun, the local newspaper, has described as “worrisome” for its refusal to disclose its members or donors — has flanked its anti-Gonzalez billboards with mailers and video ads as the group seeks to defeat her at the ballot box in November.

“If you know an election is coming, the smart thing to do is to create a negative perception far in advance,” Promises Made Promises Broken spokesperson Bruce Hoban said. “This Bea thing with ‘No, no, no, no, no’ at every trustee meeting is nerve-racking. It’s just relentless.”

Gonzalez is warm and self-effacing, with a good laugh. She said of the long campaign against her: “I think [opponents] are scratching their heads and thinking, ‘OK, we’re attacking her. We’re shaming her, and she won’t stop.’ But I really think these people have no clue the investment that I made into my community for years.”

Born and raised in Indio, Gonzalez is a College of the Desert alumna and has worked as an administrator for the Coachella Valley Unified School District for nearly 30 years. A longtime community activist, she ran for the community college district board in 2020 after hearing complaints from former students about shoddy facilities and a lack of classes and majors.

“You and I know,” Gonzalez said, “that if you want to change something, you have to be inside. And that there’s no other way.”

When she assumed office, the mother of two went through staff reports on the long-proposed new campus project. It was originally planned for northern Palm Springs, but Kinnamon announced in 2014 that the district wanted to take over a long-abandoned mall downtown and build there. Two years later, voters passed a $577-million bond to help fund that project and other improvements for existing facilities.

Gonzalez said that she’s not opposed to a new campus in principle but that putting it in Palm Springs makes no sense since there’s already a smaller facility there, and far more students reside in cities such as Cathedral City and Desert Hot Springs, which she represents.

“And so to me, I was, like, ‘Wait a minute, what is going on here?’ And all of a sudden, there was this outrage from the entire West Valley, and all these attacks started — and I mean, they went all in. Every time I would vote no on a contract or ask a lot of questions — boom! Billboard No. 1. Boom! Billboard No. 2.”

She smiled. “I figure by now, I should have at least 20.”

Hoban, the Promises Made Promises Broken spokesperson, said he didn’t “know anything about College of the Desert, anything about community college” until attending a breakfast meeting in 2021 and hearing Gonzalez criticize the Palm Springs project, then finding out the board was going to cancel a proposed Cathedral City campus.

“All the plans that had been promised for 17 years were getting heavily modified or canceled and we said, ‘Wait a second. Why isn’t anything being built in the West Valley?’”

As a 501(c)(4) nonprofit, Promises Made Promises Broken doesn’t need to disclose its members or how it spends its money. Paperwork filed with the California secretary of state lists its officers as Palm Springs restaurateur John Shay, jeweler Theresa Applegate and Cary Davidson, a Los Angeles-based attorney and trustee at Claremont McKenna College.

An email to them requesting an interview was instead returned by Hoban, who co-chaired the campaign that defeated a 2018 measure that sought to ban short-term rentals in Palm Springs of single-family homes. Asked who else belongs to Promises Made Promises Broken, Hoban said it’s “made up of people who have always been very involved in political issues and causes, so we know our way around.”

He wouldn’t disclose how much the group spends on billboards, although he claimed the going rate in the Coachella Valley for one billboard was $500 to $4,000 a month. Whatever the amount, he said his group is “100% completely” satisfied with their investment.

“People see them, and people will talk to us, and say, ‘I didn’t realize this problem with Bea Gonzalez,’” Hoban said.

Gonzalez acknowledged that she was angry when the billboards first went up, but she has made her peace with them.

“I’m getting this because I’m doing my due diligence — I ask these questions because I want that clarity,” she said. “And when the attacks started, it just made me even more curious.”

She pulled out a letter from a manila folder that she sent to California Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta’s office asking that he investigate the use of College of the Desert’s bond money over the last 20 years.

“How can I vote yes, if a yes vote would be simply because of the intimidation? I can’t do that,” Gonzalez said.

A spokesperson with Bonta’s office said it’s “unable to comment on, even to confirm or deny, a potential or ongoing investigation.”

We finished our breakfast, then drove toward the 10 to see her billboard near Indian Canyon Drive. We parked on the freeway divider and admired it from afar as traffic sped by just feet away. I told her I vaguely remembered seeing the low-slung orange thing last summer.

Gonzalez waved at the billboard, as if to say hi. Then, she cracked up.

“Well, at least they used a good photo of me!”