- In short: A West Australian researcher has demonstrated that ladybirds and their offspring can be trained to target prey.

- Biological control from beneficial insects is a tool in the global fight against pesticide resistance.

- What’s next? Farmers say spray-free farming means customers must be prepared to accept some blemishes on produce.

Farmers in Western Australia are hoping the humble ladybird will prove a valuable ally in the fight against an invasive insect that targets crops.

A researcher at Murdoch University has trained two species of ladybird to hunt down and eat the tomato potato psyllid (TPP).

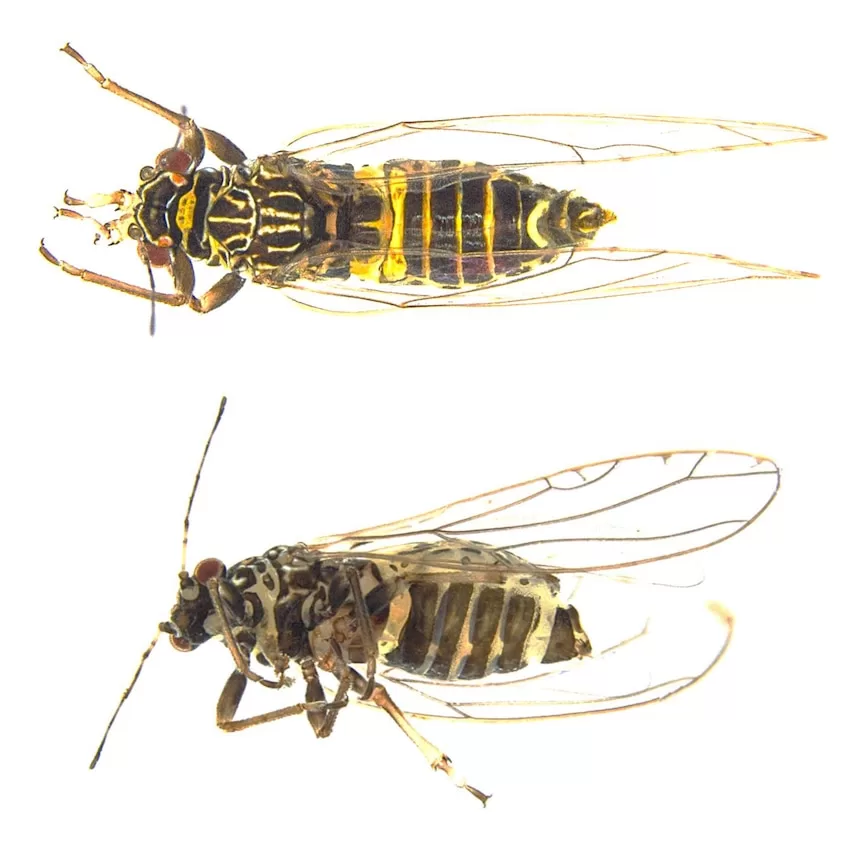

First identified in WA in 2017, TPPs are a wasp-like pest that can halve yields when it infests tomato, potato, capsicum, chilli, eggplant and sweet potato crops.

The insect can also spread zebra chip, a serious bacterial disease that has spoiled potatoes in New Zealand since 2008.

PhD researcher Shovon Chandra Sarkar said the psyllid was relatively new to the state and that ladybirds needed to be trained to recognise them as food.

“I feed them with psyllid in the lab; first for one generation or for some days,” he said.

“I found that if I train them, their babies directly start eating psyllid.”

Using natural enemies, not chemicals

Ladybirds are already used for the control of other insects and are available for farmers to buy commercially.

With many pest species developing a resistance to pesticides, Mr Sarkar said his research was part of a global trend towards biological control using natural enemies.

“It’s actually cost-effective compared to insecticide because normally some growers [spray] every two weeks,” he said.

Beneficial insects including ladybirds have been put to work at David Doepel’s property Melville Park in Brunswick for the past two-and-a-half years.

The property is home to a distillery, artisanal dairy and market garden where Mr Doepel practices spray-free agroecological farming to carefully balance “good” and “bad” insects.

“There are some things that are cute to us like ladybirds, but if you’re a psyllid or something else that they eat, then they might as well be a white pointer shark because they’re ferocious,” he said.

“It’s all a matter of scale.”

Sharing some of the crop with the bugs

Mr Doepel said using beneficial insects in food production meant the customer needed to be prepared to accept evidence of insect activity.

“The difficult side is we then have to work with our customers to educate them, that the blemishes from insects are part of the natural order of things,” he said.

“There’s a lot of insecticide use that is just for cosmetic purposes; the insect damage doesn’t really harm the value of the fruit or veg at all, but it makes it unsellable at a commercial scale.

“What we’ve been able to do is help our customers see that as a sign we’re honest about what we say that we’re spray-free.”

Stories from farms and country towns across Australia, delivered each Friday.