“There are obvious built-in themes and parameters for artists to respond to,” Muccia said of Quarters, its name a sly nod to coin-operated laundry and its quarterly schedule. Exhibits, usually advertised on Instagram, typically last one weekend since she shares the unit with a roommate who, at one opening, was visibly annoyed while wearing a robe and stomping through the party in a huff with her hamper. “A performance piece, of course,” Muccia said of her actor roomie.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

Quarters belongs to a new guard experimenting in the L.A. art scene by bringing exhibits in-house. Residences range from a Tudor mansion and Chateauesque apartment to a five-car garage and backyard cabin modeled after the Unabomber’s hideout. They’re a new spin on a nearly century-long L.A. tradition of domestic galleries that relies on word-of-mouth, neighborly trust and consummate hosts.

“When you have these residential spaces, a lot of times it’s because you want to keep the concept high and rents low,” said Danny Bowman, who started his gallery, Bozo Mag, in the revamped garage behind his rented Highland Park house. Openings tend to spill out into the patio or the emptied pool. “Instead of coming for 20 minutes, they stay for three hours,” he said.

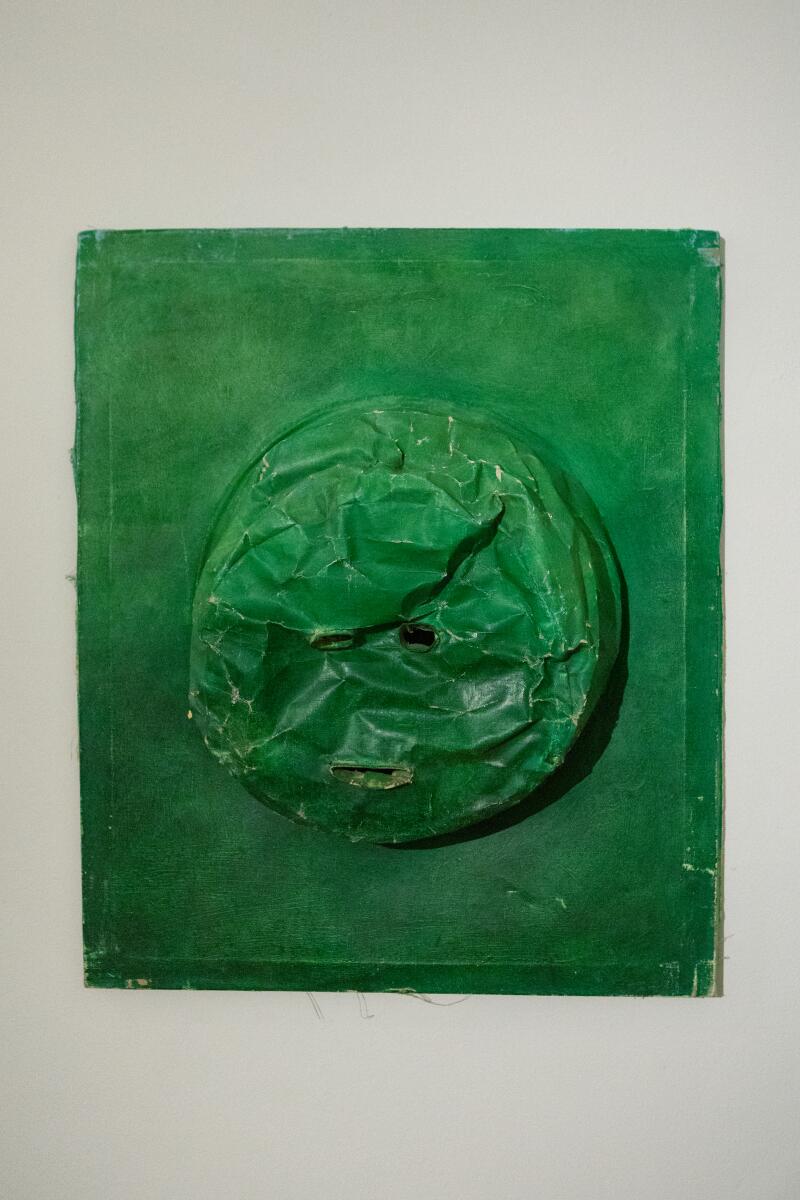

“The Weight, the Wait,” an oil on canvas by artist Molly Bounds, is part of the “Nouveau Bozeaux” exhibit at Bozo Mag.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

The emptied pool outside of Danny Bowman’s garage-turned-art gallery at his Highland home.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

High rents and the pandemic were an unexpected boon to the city’s DIY art and literary scene — from roguish takeovers at Ikea to guerrilla readings in parking lots — meshing cultural events that fall somewhere between a kegger and 21st-century salon. Angelenos in the art industry have been a sort of anchor to it all, with a new school intersecting the Venn diagram of curators and patrons, artist-run commercial spaces and art fair cool kids. Residential galleries are also defined by what they’re not: design showrooms, permanent exhibits, private collections nor endowed artist shrines. Still, they’re hard to track — either because they pop up like Whac-a-Mole or remain underground for practical reasons.

Like most residential projects today, Sea View Gallery “takes its appointment system pretty seriously,” said founder Sara Lee Hantman, treating its corner of the Mount Washington hilltop “as something sacred.” Luckily the street is an artists’ enclave, with some opening their homes up for Hantman’s dinner receptions — one in January served gumbo family-style two doors down at a local artist’s Midcentury Modern house. “So much business can be done in these types of spaces without the feeling of business being done,” she said.

It helps, too, that the house structure itself is a talking point. In the late ’90s, L.A. artist Jorge Pardo got MOCA to help fund his “social sculpture” on Sea View Avenue as an off-site exhibition that became the artist’s home studio. Spatial restrictions notwithstanding, “Pardo designed the space to not have any 90-degree angles,” said Hantman, who leases from the artist’s family month-to-month.

In L.A., where most residences are zoned “single family,” home-based businesses like these technically have a limit on visitors (one per hour) and operating hours (8 a.m. to 8 p.m.). “It’s a decidedly gray area in terms of zoning,” said Sam Parker on his namesake gallery in a rented five-bedroom Storybook home in Los Feliz. Since 2017, Parker’s openings have posed a parking dilemma for his neighbors on the winding hillside. “There comes a very real anxiety with how long we can we keep this up and get away with this until it’s a larger problem,” Parker said.

A fig vine grows around a side entrance to Bozo Mag. (Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

The entrance to art gallery “The Bunker,” located on the grounds of Danny First’s home in Los Angeles. (Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

Danny First, with his dog Diego, a 3-year-old Mexican hairless, stands next to his other art gallery, “The Cabin LA,” located on the grounds of his home in Los Angeles. In the background is a painting titled, “Dressage,” an acrylic on canvas by artist Nick Modrzewski that is part of the current exhibition, called “Modern Handshake,” running through March 31, 2024.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

His house’s domestic routine has changed, too, to include his wife and 2-year-old son (“He knows what not to touch,” Parker said.) In a bid for more legitimacy in the art world, Parker is trading the next-door model for foot traffic and will move the gallery to a storefront at 6700 Melrose Ave. in Hancock Park later this year. “First and foremost, we’re in service to our artists who are ready to have a more public-facing gallery,” he said.

The concept of the domestic museum in L.A. began at the 1920s home of voracious art collectors Louise and Walter Arensberg, according to Mark Nelson, who co-authored “Hollywood Arensberg: Avant-Garde Collecting in Midcentury L.A.” The Arensbergs kept an open-door policy for artists and art lovers to bask in nearly 1,000 works from pre-Columbian objects and Modern artists like Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí and, their favorite, Marcel Duchamp. “Even the bathroom had several Paul Klees hanging from the towel rack,” Nelson said.

Their jampacked Hollywood home at 7065 Hillside Ave. influenced artist-dealer William Copley and his short-lived but seminal Copley Galleries. For the last four years, Nelson has been rebuilding Copley’s Surrealist gallery in his Beverly Hills bungalow, which ran from 1948 to 1949. “There were probably as many or more Max Ernst paintings shoved into this domestic bungalow than there were in his entire Metropolitan Museum of Art retrospective,” Nelson estimated.

After the Arensbergs died in the 1950s, their art dealer who lived next door, Earl Stendahl, bought the property and opened the third iteration of his gallery that started inside the Ambassador Hotel. Ron Dammann, Stendahl’s grandson, and his wife, April, moved in around 1970 to help continue the business and raise their two kids.

“There were toddler birthday parties downstairs with all the breakable pre-Colombian art,” April Dammann remembered. “They played pin the tail on the donkey, and one missed dart could cost us $10,000.” In 2017, the Dammanns closed the gallery that had been operating in some capacity since 1921 and moved out of the historic Arensberg-Stendahl Home — complete with a sunroom by Richard Neutra and a carport by John Lautner.

Be it spawl or architecture, light or climate, L.A. plays a lead role in hosting experimental spaces beyond the white cube model. These DIY concepts, from pools to the L.A. River, are “crucial to the art scene in Los Angeles” that began in the 1970s, said Frieze director Christine Messineo. The influx of moneyed and blue-chip galleries over the last decade has the city competing with top art hubs like New York, Berlin and London.

Art on display at Jay Ezra Nayssan’s home in Santa Monica, where an exhibition preview party/dinner for Frieze LA was held in 2022. (Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

Art lovers view select art pieces at an exhibition preview party/dinner for Frieze LA held in Jay Ezra Nayssan’s Santa Monica home in 2022.

(Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

In response, or perhaps opposition, to the gallery boom, curator Jay Ezra Nayssan started Del Vaz Projects out of his West L.A. apartment in 2014. “Everybody eats, everybody drinks, everybody’s invited,” said Nayssan, who now runs Del Vaz as a nonprofit in his Santa Monica home with his partner, Max Goldstein. “We don’t operate in this realm of exclusivity and scarcity, which is inherent in the commercial art world today.”

Joseph Geagan, a painter from the New York and Berlin art world, doesn’t think his buzzy penthouse gallery in Koreatown’s landmark Gaylord Apartments would have worked elsewhere. “There’s still a Wild West element for experimentation here,” he said of his “spooky, ‘Shining’-esque” building, which turns 100 this year. It’s a mythos that Geagan didn’t bother competing with; the apartment building and gallery share the same name. (Exhibit spectators usually end up at the HMS Bounty dive bar downstairs afterward.) He’s run Gaylord Apartments since 2021 with his boyfriend, John Tuite, in their living room with glittering views of Koreatown — windows framing the Hollywood Sign and Griffith Observatory are in the next room. It’s more a social spot than a moneymaker, and Geagan makes a habit of showing early or mid-career artist-friends outside of L.A., making shipments and travel the bulk of the expenses. “And rent, of course,” he said.

The lower barrier for entry inspired Harley Wertheimer to open Castle Gallery in his dining room two years ago. He’s since quit his gig as vice president of A&R at Columbia Records and expanded the showroom into an empty unit downstairs, where weekend morning receptions come with a latte cart and bagels in the courtyard. Named for its historic 1920s Chateauesque building, Castle is a treasure box of prewar charm: lattice windows, crown-molding, wainscot, Art Deco tile.

Wertheimer views residential and commercial galleries like the so-called California Double — surfing in the ocean and snowboarding in the mountains on the same day — one just as fun (and valid) as the other. Democratizing the business doesn’t have to mean watering it down, and art sold in a home isn’t mere decoration. “There’s definitely a desire from me and my peers to be treated as any other gallery,” he said.