Next to him were three men in body armour and green uniforms, with no insignia.

The crowd of men, aged 20 to 50, were gathered outside a white Stalinist-era government building in Sevastopol, a port in Ukraine’s Crimea.

They were uphill from the seashore, next to huge sequoias, blossoming cherry trees and elderly ladies holding hand-written posters that read, “In Russia through a referendum” and “I want to go home to Russia.”

Eight days later, Moscow would hold a “referendum” on the Black Sea peninsula’s “return” to Russia, and the men were a nascent “self-defence unit” that would “prevent provocations,” the man said.

I approached them with a notebook and a dictaphone – and was immediately seized by two “volunteers”.

“Got a spy here!” they yelled, twisting my arms and ready to beat me to a pulp.

But the instructor told them and me to wait.

He kept on talking for half an hour, telling the crowd that they would train at a military base outside Sevastopol and should arrive in “comfy clothes” and sneakers.

One of the volunteers asked him whether they should bring firearms. Many others nodded approvingly.

“When you take up arms, we become an armed criminal group. But if something happens, each unit will be backed by fire,” the instructor said.

After the meeting, he checked my press ID and told me he was a retired intelligence officer who had served in Russia’s volatile North Caucasus region and arrived in Crimea as a “volunteer”.

“Our groups will have to respond to challenges, provocations because there is a shortage of policemen in town,” he told me. “There’s NATO propaganda at work.

“Our aim is to prevent the first shot. If the first shot happens, you won’t stop the mess,” he said.

He politely declined to say what his name was.

‘Little green men’

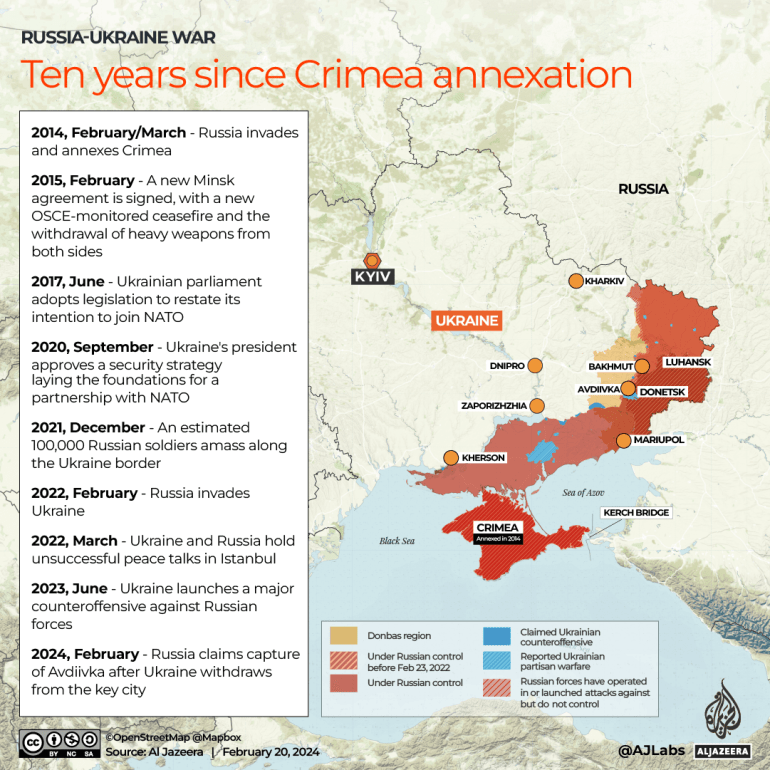

The first shot didn’t happen, but what took place in Crimea 10 years ago paved the way for today’s war between Ukraine and Russia.

On February 20, 2014, Vladimir Konstantinov, speaker of Crimea’s regional parliament and a Russian politician, said he “didn’t rule out” the peninsula’s “return” to Russia.

On the same day, thousands of gun-toting men in unmarked uniforms appeared throughout Ukraine’s Crimea.

They responded to the victory of pro-Western protests in Kyiv that would within days remove pro-Russian Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych.

Dubbed “little green men” or “polite people,” the servicemen didn’t interact with locals or reporters, while Russian President Vladimir Putin said in Moscow that “they are not there”.

They appeared next to Ukrainian military, naval and air bases, and the interim government in Kyiv ordered Ukrainian servicemen in Crimea to leave without firing a single shot.

Many servicemen – along with thousands of police officers and government officials – joined the pro-Russian “government” formed by Sergey Aksyonov, a minor political figure and former mafia boss nicknamed “Goblin.”

Some servicemen were detained, including Ihor Voronchenko, deputy head of Crimea’s coastal defence at the time.

“There was a solitary cell, without a window, when you lose the sense of time, space. It affects one psychologically,” Voronchenko told me in 2018 when he was head of Ukraine’s navy.

No shots were fired, but blood was spilled.

On March 4, a “self-defence” unit abducted a Crimean Tatar protester, Reshat Ametov.

He was held with other hostages in Simferopol, Crimea’s administrative capital, and tortured for a week.

His naked, bruised body was found on March 15, head wrapped in plastic, eyes poked out.

A day later, the “referendum” took place.

Only a handful of schools and government buildings were used as “polling stations” so that the jubilant pro-Russian “voters,” mostly the elderly nostalgic about their Soviet youth, would throng and fill them, creating an illusion of mass vote.

Moscow said 90 percent of Crimeans voted to join Russia, but the “referendum” was not recognised by Ukraine or any other nation.

On March 21, Russian President Vladimir Putin made Crimea part of Russia.

The annexation propelled his sagging approval ratings to an atmospheric 88 percent, and some Russians saw it as a first step to restoring the USSR.

In response to the Arab Spring, a series of mass protests in the Middle East, the Kremlin came up with the idea of a “Russian Spring,” stoking protests in Russian-speaking Ukrainian regions in the east and south.

Why Crimea?

Ancient Greeks, Romans, Mongols and Turks contested Crimea, the westernmost end of the Great Silk Road.

It became a jewel in the crown of Russian czars, who annexed it in 1783 from the Crimean Tatars, whose Muslim state was ruled by the descendants of Genghis Khan and allied with Ottoman Turkey.

The czars and communists understood Crimea’s utmost strategic importance in controlling the Black Sea, and Nazi Germany occupied it during World War II.

Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin accused Tatars of “collaborating” with the Nazis and ordered their entire community of 200,000 deported to Central Asia.

“Early in the morning, there was a loud bang on the door. I yelled, ‘Mum, Dad is back from the war! But there were two soldiers who told us to start packing,’” historian Nuri Emirvaliyev, who was 10 at the time, told me about the May 18, 1944 deportation.

More than half of them died en route, including his younger sister.

“During stops, soldiers yelled, ‘Got any dead? Bring them out!’” Emirvaliyev recalled.

The rare survivors and their descendants were allowed to return to Crimea in the late 1980s only to see their homes occupied by ethnic Russians and Ukrainians and become a distrusted and vilified minority.

Crimea was made part of Soviet Ukraine in 1954 during the construction of the North Crimean Canal which made agriculture in arid interior areas possible and triggered the growth of urban centres.

Moscow turned Crimea into a Soviet Riviera, and millions of former Soviet citizens still reminisce about their holidays there.

After the 1991 Soviet collapse and Ukraine’s independence, Crimea remained predominantly Russian-speaking, its residents were mostly loyal to Moscow, and Russia’s Black Sea Fleet was based in Sevastopol.

‘Died for nothing’

Since the 2000s, Russian politicians, including Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov, began visiting Crimea and openly urging its residents to “reunite” with Russia.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian political elites didn’t pay much attention to the peninsula’s development and allowed graft to thrive, “thinking that corruption would tie local elites to central ones,” Kyiv-based analyst Aleksey Kushch told Al Jazeera.

But the practice misfired in 2014, when Crimean elites saw the success of the pro-Western revolt in Kyiv, got scared of “responsibility for the corruption,” and preferred the annexation, he said.

The annexation was followed by the arrival of Russian officials – and the transformation of endemic corruption.

They conducted a massive revision of ownership rights and expropriated thousands of properties, including beachfront hotels, vineyards, a film studio

Alexander Strekalin, 75, resisted the takeover of his small cafeteria in the port of Yalta.

In September 2017, he doused himself with acetone, flicked a lighter and died three agonising days later.

“He died for nothing,” his widow Mila Selyamieva told me.

Meanwhile, the Kremlin and pro-Moscow authorities initiated a crackdown on critics, including secular dissidents and religious Crimean Tatars, sentencing dozens to jail for alleged “extremism” and “encroachment on Russia’s constitutional order”.