On-set sound mixer Steven Morrow recalls it as a terrifying proposition — miking 200 chorus and orchestra members performing live in an echoey cathedral. So, he huddled with re-recording mixer Tom Ozanich, with whom he’d also worked on Cooper’s “A Star Is Born.” On that film they recorded all the singing live, but this was different.

“With vocals it’s harder to fake,” notes Morrow. “With music you can fake it a little bit. But the overall experience with this performance and the orchestra playing this music, it jumps off the screen because it is real. And the whole movie is played that way where it’s real. If you cheat it, you lose some of that.”

They had three days to get it. In addition to their own Dolby Atmos mikes on timpani, horns and opera soloists, they hired Classic Sounds of London, who have miked the Ely Cathedral before. Sixteen microphones were set up in all, some suspended from above.

(Jason McDonald / Netflix)

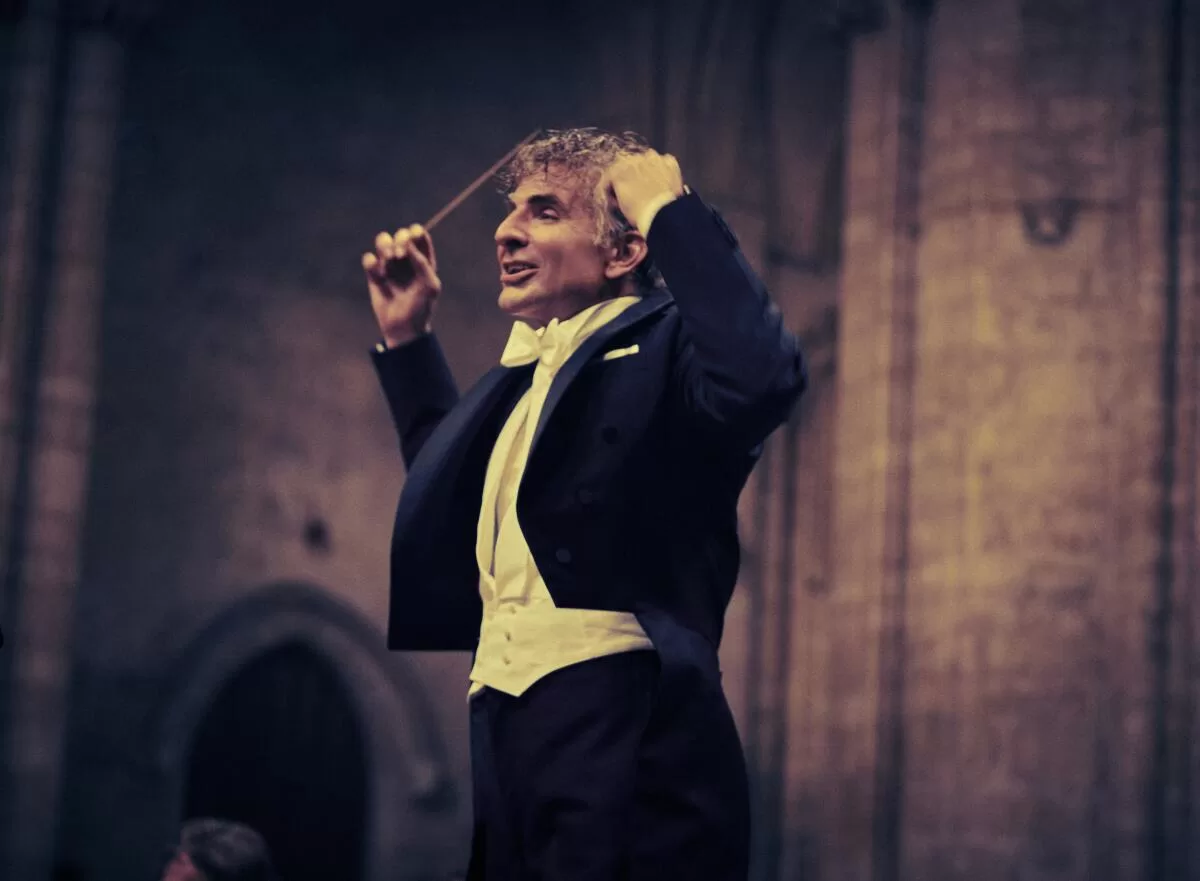

“The first day was a wipeout in the conducting aspect of it,” Ozanich recalls. He is nominated twice this year, for “Maestro” and “The Creator,” bringing his total Oscar nominations to four. “Bradley was really good about having the instinct to know he wasn’t great. And the London Symphony Orchestra is good enough that they ignore him and move on and do their thing. So, he came in and said we’re going to do it again. We’re going to do one long Technocrane shot. And the orchestra came up to him after and said. ‘That was it, you really conducted it.’ So, I think that’s where the decision to go live versus faking it, because he could feel it in his own performance the day before, it wasn’t that great.”

The scene in the film is roughly the take described by Ozanich — a six-minute Technocrane shot on Cooper conducting, intercut with B-roll of musicians and choral members. It’s an uplifting and deceptively simple-seeming reproduction of the original 1973 performance with the camera moving in time with the music.

The movie’s other great challenge came with party scenes, of which there are many. The usual method is to mike the principals and lay in group effects in post. Not on “Maestro.” Group scenes here required everyone to be miked. Cooper had seen a movie Morrow and Ozanich made with Jason Reitman called “The Front Runner,” on which they miked everyone in crowd scenes, and requested the same.

“When you ask people to fake talk, they over-exaggerate when they’re doing it because they’re not actually doing it,” notes Morrow. With so many people talking at once, they bleed into each other’s mikes, creating headaches for him. “Other mikes are picking up somebody and it does some weird things to the sound. So, you have to be able to dodge around that stuff. And the group and effects crowd in there help to fill it in and give us some layers of depth.”

“It’s an avalanche of audio,” laments Ozanich. “It’s a ton of dialogue because you’re locked into it and when you cut back and forth between takes, there’s going to be jumps.”

The audio was orchestrated throughout, as with a symphony, including every detail from Cooper’s rhythmic delivery of lines (which he kept up between takes), to the birdsong in the background of a bucolic setting, to a sudden gust of wind. Such keen attention to craft is part of what garnered the film seven Oscar nominations in all, including best picture and lead actor for Cooper.

“He’s very interested in collaboration as opposed to workers doing their job,” Ozanich says of Cooper. “He wants you to have an opinion, have some input and partake in it. I watched him learn very rapidly on ‘A Star Is Born.’ You could tell he was becoming a student of sound. He was trying to understand it.”

Both Ozanich and Morrow were nominated for “A Star Is Born,” and Ozanich received another for “The Joker.” They’re currently working together on “Joker: Folie à Deux,” and Morrow is working on “Juror #2,” reuniting with Clint Eastwood, with whom he’d worked with on 2018’s “The Mule.”

“We run a tight set to make sure we’re not wasting valuable time,” he says of working with the 93-year-old icon. “Everybody is on the same page trying to get what he wants.” As for the legendary Eastwood one-take method, he says, “I’ve always heard that, but working with him, he’ll be happy to take another one or two. And if the actors said, can I get another one? No problem at all. He gives it to them. But for the most part, we don’t do many takes. Clint’s very focused on what he wants.”

For Ozanich, the recognition from his peers that comes with a nomination is an award in itself. “There are so many great artists and people in this business that inspired me and I look up to the work they did. And to have those people say, ‘Whoa, you did a really great job on this!’ That’s the award. ‘Maestro’ is a very unique sound job and you never quite know if people are going to get it, or appreciate it for what it is. So, I think that would be the biggest thing. Wow, they got it.”

Morrow’s first nomination was for “La La Land.” “When we lost, I felt devastated for weeks because you figure that’s it, I’m never going to get nominated again. Then it happens a few more times and now, I don’t know, you’d have to ask me after the win, if we win. But I feel like it’s a special experience to be included in the discussion of what people found great for the year. For me, that’s it. You look at a guy like Bradley who’s been nominated 12 times, hasn’t won. I don’t think that lessens the amount of sacrifice he did to get there. I think that’s the same for all of us. But you hope the producers that usually hire you don’t think all of a sudden you’re twice the price, because you’d never get hired again.”