- In short: A Grattan Institute report says one third of Australia’s 4 million school children are being failed by an education system that persists with discredited theories to teach reading.

- Students lacking reading skills are more likely to fall behind, disrupt class and end up unemployed or jailed, coming at an estimated cost to the economy of $40 billion over their lifetimes, the report concluded.

- What’s next? Governments and school systems are being urged to commit to what’s known as “structured literacy”, a mix of direct instruction and phonics.

One third of Australian students are failing to learn to read proficiently, at an estimated cost to the economy of $40 billion, according to a new report.

The Grattan Institute’s Reading Guarantee report calls this a “preventable tragedy” caused by persisting with teaching styles popular at universities, but “contrary to science” and discredited by inquiries in all major English-speaking countries.

“In a typical Australian school classroom of 24 students, eight can’t read well,” said report lead author and Grattan education program director Jordana Hunter.

“Australia is failing these children.”

The estimated cost of this “failure” was profound both personally and economy-wide, with students unable to read proficiently more likely to become disruptive at school and unemployed or even jailed later in life, the report concluded.

Dr Hunter said the “conservative” financial estimate amounted to a “really significant cost” that did not include productivity benefits from increased reading.

Students left to ‘guess’ meaning of words

The Grattan Institute attributed the major cause of its findings to the rise of a teaching style called “whole language”, which became dominant on university campuses in the 1970s.

It is underpinned by a philosophy that learning to read is a natural, unconscious process that students can master by being exposed to good literature.

Proponents say it empowers young people by giving them autonomy.

However Grattan said it left students to “guess” the meaning of words and was saddling parents with expensive tuition costs to help their children catch up.

What are the reading wars?

- Since the 1980s there has been conflict over the best way to teach reading

- The “whole language” approach emphasises student-led learning and claims reading is easy and natural

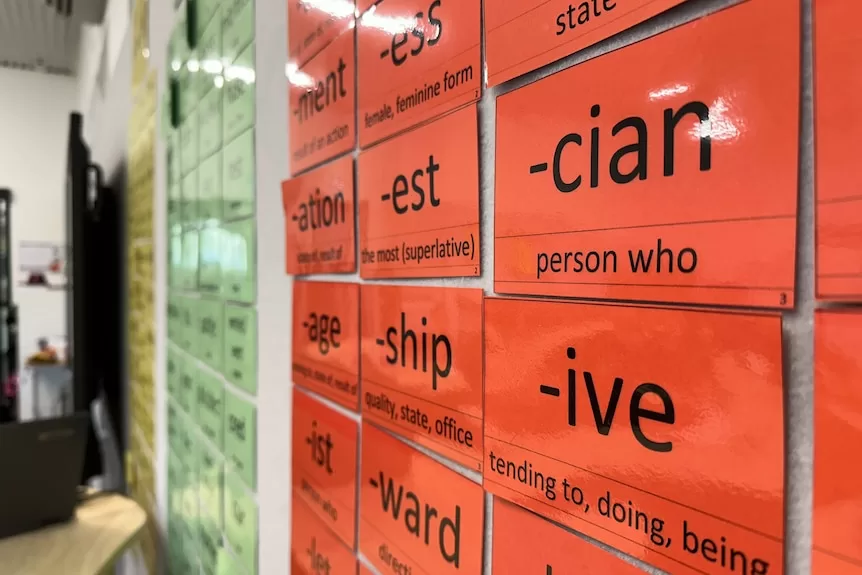

- Phonics, or sounding out words, is part of the “structured literacy” approach, which says reading should be broken down and the elements taught explicitly

After decades of the so-called reading wars, “whole language” has incorporated elements of other approaches such as phonics, but Grattan said it remained “light touch” and “contrary to scientific recommendations”.

“What we need to do is set our expectations higher. We need to stop accepting failure,” Dr Hunter said.

“It’s not good enough that one in three students are not where they need to be in reading.”

The Grattan Institute said evidence showed a much greater number of students learned to read successfully using the alternative “structured literacy” approach, and at least 90 per cent of students would be proficient using this model.

“Structured literacy” includes phonics, but also teacher-led “explicit instruction” backed by the latest science on how children’s brains learn new concepts.

“The quality of teaching is the thing that will shift the dial for our young people,” Dr Hunter said.

“We need to make the most of every single minute we have with our young people.”

Why are some schools still not using phonics?

Despite major inquiries in Australia, the United Kingdom and United States settling the argument that structured literacy teaching is superior, that hasn’t flowed to all classrooms, the Grattan Institute said.

It said where school systems have embraced it, students have reaped the rewards.

Australia’s 10,000 schools have a high degree of autonomy, and even in states where education departments advocate for the structured literacy approach, the report said there needed to be more support for teachers to re-train and be provided with ready-made lessons.

“The real issue here is, are governments doing enough to set teachers up for success?'” Dr Hunter said.

“The challenge is making sure best practice is common practice in every single classroom.”

Do you have a story to share? Email [email protected]

Western Sydney University’s Katina Zammit, president of the Australian Literary Educators Association, said the whole language method should not end up in history’s trash can.

She said that in school systems that moved to the teaching methods championed by the Grattan Institute, some teachers found it too prescriptive.

“The teachers that I have had contact with, some of the children who are being taught this way, have either lost interest in reading because it’s a whole class approach or they are not retaining the instruction,” Dr Zammit said.

Dr Zammit agreed whole learning did not work for all students but said it could still be useful in the classroom.

“One size doesn’t fit all students,” she said.

“Yes, the majority it might, but we do have to look at engagement and motivation as well.”

However in a statement to the ABC, Education Minister Jason Clare said the science on teaching reading had been settled.

He also foreshadowed mandating teaching styles in the upcoming school funding agreement.

“The reading wars are over. We know what works. The current National School Reform Agreement doesn’t include the sort of targets or reforms to move the needle here,” he said.

“The new Agreement we strike this year needs to properly fund schools and tie that funding to the sort of things that work. The sort of things that will help children keep up, catch up and finish school.”

Loading…