Behind the scenes, Harris’ advisors have a different question: Who can she meet with?

Worries over extensive government corruption in the region, particularly in Honduras, underscore the challenge Harris faces in leading the Biden administration’s diplomatic efforts to reduce immigration from the countries that make up the so-called Northern Triangle, which also includes El Salvador and Guatemala. While Harris is supposed to focus on the conditions that drive so many people to leave home, such as poverty and violence, some of the leaders she must meet are considered complicit in those problems.

Harris has resisted setting specific goals since President Biden tapped her for the assignment, her first solo task as vice president, on March 24. She and her advisors have emphasized repeatedly that she is not directly responsible for conditions at the border, including a record influx of unaccompanied children.

But Harris’ piece of the problem, addressing the root causes that lead families and children on the dangerous journey with smugglers, or even on their own, also has diplomatic and political pitfalls — including for Harris’ longer-term ambitions.

At stake, too, are the safety and well-being of millions of people in those countries. The region has been afflicted by poverty, hurricanes, drug cartels and gang violence, a combination that Harris called “the most intractable issues” in a recent interview with The Times. Those have been exacerbated by corruption at the top.

“This is not going to be fixed overnight,” Harris said, lowering expectations.

The administration needs to build “incentives for investment in those communities,” she said, but it has yet to lay out a comprehensive strategy her advisors say is needed.

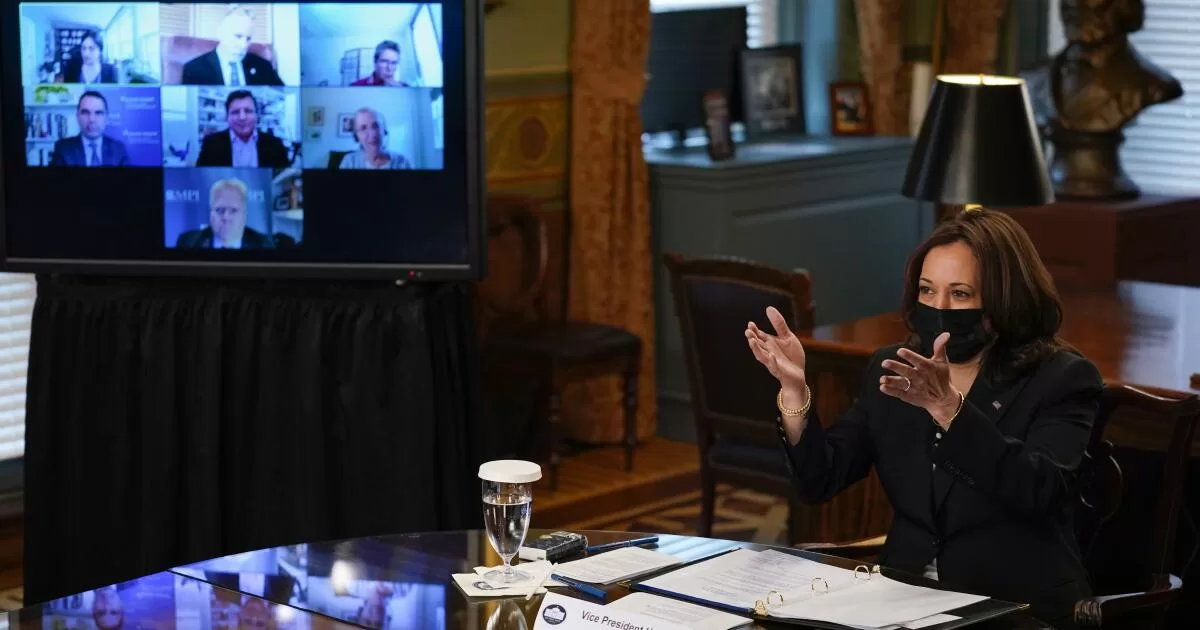

During a virtual White House meeting with experts on Wednesday, Harris said she would be guided by the belief that most people do not want to leave their homes unless they face harm or believe they can no longer meet basic needs. Residents must be given “some hope that if they stay at home, help is on the way,” she said.

Harris confirmed that she would not be visiting the border, but that she planned to travel soon to Guatemala as well as to Mexico, which, as the final stop for many Central Americans unable to cross into the United States, is also involved in Harris’ diplomatic initiative.

A senior advisor said Harris would begin virtual meetings with regional leaders in the next few weeks, followed by in-person travel in a month or two, assuming a loosening of COVID-19 restrictions by then.

Harris has spoken with leaders of Mexico and Guatemala, but she has yet to speak with Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele, an authoritarian leader, or Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, who was an ally of former President Trump and whose brother was recently sentenced to life in prison for drug trafficking by a federal judge in Manhattan in a case that implicated the Honduran president.

The advisor said “we are working on engagements and thinking through the right approach” in those countries, which could include bypassing Hernandez and meeting with lower-level officials and nongovernmental organizations. Those efforts pose their own challenges. The nongovernmental groups in the region are ill-equipped to handle up to billions of dollars in American aid money, according to experts.

Recent travel to the region by Ricardo Zúñiga, the administration’s top envoy, left little optimism that the solution will be quick or easy.

Testifying to a congressional subcommittee Wednesday, Zúñiga fended off questions from Republicans on why neither he nor Harris had visited the border. The Republicans described the situation there as a crisis, one they blamed on the Biden-Harris team despite migrant influxes during the Trump administration.

American officials who have visited the region have underscored the quandary for Harris.

“There are whole big swaths of El Salvador that are essentially being run by violent gangs,” said Rep. Zoe Lofgren, a San Jose Democrat, who traveled to the country in 2019. “It was described to me as like [Islamic State] without the religion.”

But even as Lofgren compared the situation to the challenges the American military faces in the Middle East, she noted the U.S. would have even less direct control over the results: “We will not be sending in troops … we will be assisting those who are trying to retake their country, for civil society.”

For generations, Central America has been a region rife with corruption and conflict. Wealth and power reside in the hands of a few, while growing populations struggle for jobs and opportunity amid endemic poverty. The U.S. has poured humanitarian and development aid into El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and other countries, but also has used them as staging grounds in proxy wars.

Such dire conditions, exacerbated by two Category 4 hurricanes within two weeks last year and now a raging pandemic, have combined to propel millions of migrants northward to the United States. Biden’s election has provided added motivation for some who believed that his promises to overturn Trump’s hard-line policies would mean more opportunities for refugees.

As her model, Harris has touted Biden’s efforts in leading a similar effort to stem migration from Central America in 2014, when he was vice president. But the nearly $1 billion the United States funneled to governments and international companies then did not have a sustained impact. Conditions have worsened, corruption has deepened and government leaders have proved unreliable.

“There was a sense you could just cajole these presidents and now we know … it’s no longer enough to say, ‘C’mon, guys,’” said Eric Olson, who co-wrote a recent report reviewing prior efforts with Zúñiga, before Zúñiga became Biden’s envoy to the region.

Olson said Biden’s typically folksy approach as he stood on a stage with notorious characters such as Hernandez and Jimmy Morales, then-president of Guatemala, struck the wrong note.

“We know we have to be much tougher,” he said. “There have to be carrots and sticks. There have to be sanctions. We have to call them out, while offering opportunities.”

The report Olson published in December with Zúñiga for the Wilson Center, a nonpartisan think tank, covered efforts of the Obama and Trump administrations from 2014 through 2019. While Biden officials blame Trump for cutting off aid in 2019, the report points to problems with assistance efforts under both administrations, including local administrators’ fear of reporting bad news up the chain, further undermining the programs’ effectiveness.

Another report by a faith-based group called the Root Causes Initiative, which includes members from the United States, Mexico and Central America, pointed out that less than 5% of the U.S. foreign aid in the last decade went to local groups, and less than 1% was spent on water and sanitation projects — “critical priorities for civil society.”

Biden “will be first to admit that he’s learned things,” advisor Roberta Jacobson said in a March interview.

Jacobson, who announced Friday that she is stepping down as Biden’s border czar at the end of the month, said Harris should work with a cross-section of local government leaders and nonprofit agencies, and impose strict controls, so that “in the end, you are strengthening the societies and not enriching these governments.”

Harris’ advisor described it as a two-pronged approach: finding short-term programs to alleviate suffering and secure local immigration controls, while initiating longer-term programs to build civil society and root out corruption.

Though Harris faces immense pressure to deliver quick results, some specialists in the region urge patience, given the lack of reliable partners.

“There is a lot of pressure to get things moving,” said David Holiday, an expert on Central America at the Open Society Foundations. “How are they going to avoid making the same mistakes of throwing money at the problem and expecting short-term results? There needs to be more flexibility, a longer timeline.”

But the political timeline may be much shorter, especially given Republicans’ eagerness to make Harris the face of the immigration crisis.

Carlos Curbelo, a Republican former congressman from Florida who tried to work with Democrats on immigration legislation that his party opposed, compared Harris’ assignment to the one Trump gave Vice President Mike Pence, leading his administration’s response to COVID-19.

“It’s just an extremely difficult assignment that will be pain no matter what you choose,” he said.

He predicted the immigration issue could cost Democrats their congressional majorities in the 2022 midterm election. “This,” Curbelo said, “is a headache that will not go away for this administration.”

Times staff writer Seema Mehta contributed to this report.